The Liberal Party and the rule of law

Shannon Gormley: The striking similarities between what some Liberals say about China and what some Liberals say about SNC-Lavalin

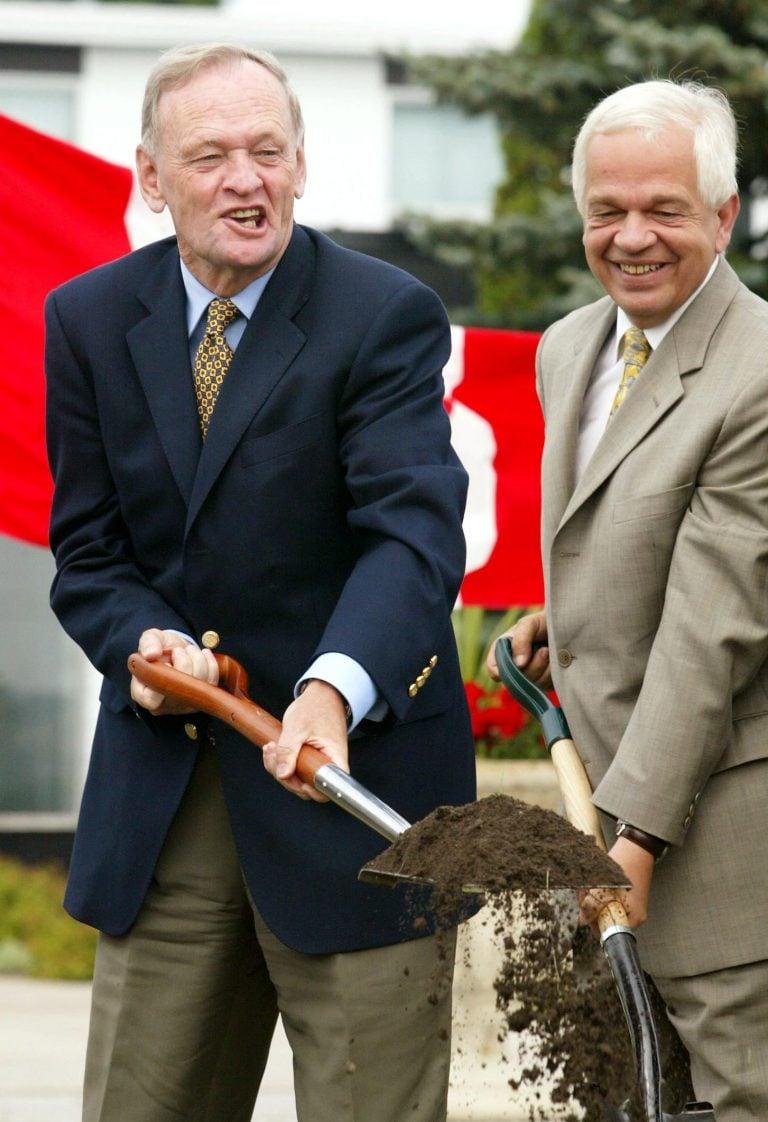

Chretien and McCallum take part in a ground-breaking ceremony at Canadian Forces Base North Bay, Ont., on Aug. 20, 2003 (Jonathan Hayward/CP)

Share

Liberals admit this much: executives at a powerful corporation may have done some bad things—so bad, they led to criminal charges. Still, the powerful corporation is powerful, senior Liberals warn. If the justice system does not cut a deal, the corporation will make life difficult for Canada. With financial and political ties to Liberal higher-ups, the corporation could make life difficult for the party, too.

Some senior Liberals draw the inevitable conclusion: prosecutors must have made a mistake. The attorney general should intervene in the prosecution and give the corporation what it wants. That way, these Liberals say, Canada can get what it wants. And Liberals—they do not say—can get what they want, as well.

Liberal partisans may be relieved to hear that this is not yet another summation of the SNC-Lavalin scandal. They wish to cease all mention of it. It’s odd, then, that some party stalwarts seem bent on reenacting it.

Meng Wanzhou, a citizen of a powerful state and an executive of a powerful corporation, China’s Huawei Technologies, with close ties to the Chinese state, allegedly defrauded an American bank; prosecutors in the United States Department of Justice charged her with fraud; Canada, honouring an extradition treaty with its neighbour and ally, arrested her the December before last. Having kidnapped two Canadians and banned various Canadian agricultural products, China has demonstrated that if Canadian courts do not let her go, it will make life difficult for Canada; having ties to senior Liberals, China could make life difficult for the party, too.

READ MORE: Chrétien’s China and Trudeau’s

These Liberals have concluded that the prosecution of Meng must be a mistake. The attorney general, they say, should intervene to forestall her prosecution and give China what it wants so that Canada can get what it wants. And certain Liberals—they do not say—can get what they want, as well.

There are differences between the two cases. This time it is senior party members, not senior government officials, who are petitioning the attorney general to spare an alleged criminal from going to trial—indeed, the Prime Minister, who led the attempted interference in the SNC-Lavalin affair, has reportedly decided the government will not intervene in Meng’s extradition.

But there are similarities, as well. What does it say about the culture of the Liberal Party that such important party higher-ups as former prime minister Jean Chretien, his former chief of staff Eddie Goldenberg, his former finance and foreign affairs minister John Manley—all of whom now work for firms and businesses with close relationships with Chinese companies, including Huawei—as well as his former defence minister John McCallum—who Trudeau dispatched to China as ambassador—are so confident they will get a hearing when they argue the government should capitulate to China’s demands? What does it say about the Liberal Party’s commitment to the rule of law that their arguments bear so many striking parallels to those made in defence of Justin Trudeau’s capitulation to SNC’s demands?

How many parallels? Consider:

Advising politicization

Once again, senior Liberals are demanding the attorney general take the virtually unprecedented step of interfering in a criminal case for political reasons, compromising the independence of the judicial system and undermining the rule of law.

With SNC, the Liberal government, in response to the company’s persistent lobbying, pressured the attorney general to override the prosecutor’s decision and allow the corporation to avoid a criminal trial. With China, senior Liberals are urging the current attorney general to do much the same with respect to an extradition proceeding, exercising his ministerial prerogative to refuse to surrender Meng to U.S. authorities.

In both cases, the same precedent would be set: that those with political connections and financial leverage can keep their friends out of trouble.

Relativizing rule of law

Once again, senior Liberals are implying that the rule of law is a mere preference rather than a democratic necessity. Liberals painted the SNC scandal as a policy dispute—some members of cabinet preferred the independence of criminal prosecutors, while others valued jobs.

With China, senior Liberals present China’s hostage-taking as a cultural dispute—some cultures prefer impartial justice, while others do not.

McCallum, for one, thinks Canada has more in common with China than the United States now; others advise Canadians to be more “understanding” of China. But when Goldenberg says “it is essential to understand where the Chinese are coming from” in seeing the extradition request as part of an American persecution campaign against the regime and Huawei, he more than understands the Chinese—he appears to agree with them. He writes, “Obtaining [our hostages’] freedom should have nothing to do with how we feel about China.”

“How we feel.” There are no facts, only a rich mosaic of perceptions and emotions. Who are we to say that protecting an impartial judiciary is better than surrendering to a dictatorship that illegally kidnaps and tortures another country’s citizens as revenge for that country having honoured its treaty responsibilities?

Blaming the prosecution

Once again, senior Liberals have scapegoated prosecutors for fulfilling their professional duty—taking a criminal case to trial when in their judgment it should go to trial. With SNC, Liberals accused the director of public prosecutions of not having made the correct judgement, while expressing rather less concern about the corporation’s judgment in bribing members of a brutal regime.

With China, senior Liberals are implying American prosecutors are either supine or crooked. Ostensibly, they blame Trump for the criminal charges that led to the extradition request, which is partly why McCallum advised Chinese-language state-owned media that Meng has “quite a strong case”.

But the charges were brought by the United States Department of Justice. To claim, as they do, that the prosecution is politically motivated is to suggest that Department of Justice attorneys allowed their independence to be utterly compromised by Trump’s administration—or if Trump is left out of it, that prosecutors took it upon themselves to compromise their impartiality by using Canada for political purposes.

Either way, when Manley says “The U.S. created the mess we are in”, or when Chretien calls the issue, “a trap that was set to us,” their logic dictates it is prosecutors who must in fact be substantially to blame—not the alleged fraudster, nor the controversial multinational that employs her, and not the dictatorship that seeks to protect them both by kidnapping Canadian citizens.

Blaming the attorney general

Once again, senior Liberals have extended the blame to the attorney general for not interfering in a prosecution. With SNC, the “difficult” and “selfish” former attorney general, Jody Wilson-Raybould, was said to have erred in respecting the foundational principle of prosecutorial independence and refusing to intervene. With China, Manley says the former attorney general is “on the hook” for failing to exercise “a bit of creative incompetence” and “somehow just miss [Meng]”; Goldenberg claims it is now the current attorney general’s duty to “address whether there is a way” to stop the extradition.

In both cases, Liberals have called on the attorney general to betray the principles of the justice system she or he is charged with protecting in submission to the threats of a bully.

Prioritizing legal loopholes

Once again, senior Liberals argue that such a radical departure from legal norms is justified by the mere existence of legal loopholes. With SNC, they noted the attorney general had the formal authority, in exceptional circumstances, to override a prosecutor’s decision to go to trial, and concluded that this authority trumped her obligations to impartial justice. With China, they note that the attorney general has the formal authority to end the extradition process, and conclude that this authority trumps the same obligation— even when it means setting a precedent of putting Canada’s justice system at the mercy of a rogue state.

Conflating partisan interests with Canada’s

Once again, senior Liberals justify violating the norms of justice in a criminal case in the name of a supposedly larger public interest, though other, distinctly private interests are in fact at stake. With SNC, the company’s threat of job losses was used as public justification for interference; Wilson-Raybould testified before a Commons committee that behind closed doors Trudeau cited his own political considerations as a rationale. With China, the regime’s threats to Canadian citizens and farmers are invoked as justification for interference. No one has to mention party members’ political considerations—the relationship of senior Liberals to Chinese interests is well-documented. In both cases, Liberals gloss over a potential conflict of interest that could jeopardize Canada’s rule of law.

Advising the attorney general to politicize a criminal prosecution; suggesting the rule of law is a relative thing; attacking prosecutors for upholding the rule of law; attacking the attorney general for upholding prosecutorial independence; claiming legal loopholes trump democratic fundamentals; advocating for an outcome that could benefit their own interests but undermine the country’s. I admit, the Liberals have a point: it would be nice if everyone could finally stop talking about SNC-Lavalin.