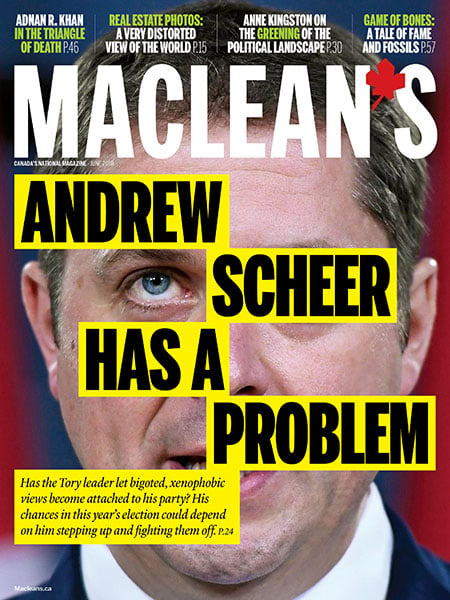

Andrew Scheer has a problem

The Conservative leader has left himself open to charges of intolerance in his party. It could be the biggest, ugliest issue in the coming election.

Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer faces reporters in Ottawa (Sean Kilpatrick/CP)

Share

As political oratory goes, the three-minute speech Andrew Scheer delivered on the snow-covered lawn of Parliament back on Feb. 19 wasn’t exactly deathless. “We’ve got your back, we are standing with you” was pretty much the essence of what the federal Conservative leader told a few hundred riled-up oil and gas workers whose truck convoy had travelled from Alberta to Ottawa under the banner “United We Roll,” picking up along the highway an assortment of sympathizers and more than a few problematic hangers-on.

It was those elements in the throng, not Scheer’s got-your-back boilerplate, that lent the moment lasting significance. Making common cause with disgruntled energy-sector workers—who are mad at Justin Trudeau for pricing carbon and not yet getting a new oil pipeline built—were the self-styled “yellow vest” protesters. They often seemed more agitated about asylum-seekers crossing the border into Canada from the U.S. than any oil-patch issues, and were prone to accusing the Prime Minister of “treason” for supporting the UN’s new Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

A little while after Scheer’s brief remarks, on the back of a truck parked on Wellington Street, outside the official demonstration zone authorized by Parliament Hill security, a guy hollered over a portable sound system, “Faith Goldy is in the house, shut up and listen!” Although she is far from a household name, Goldy has cultivated a far-right following since she was fired in 2017 by Rebel Media—the online outlet for anti-Justin Trudeau, pro-Donald Trump, anti-Muslim immigration bile—after appearing on a neo-Nazi podcast. Opposing left-wing demonstrators did their best to drown her out, but her cry of “No more Trudeau! Our borders will be protected!” cut through the din.

After that, it didn’t matter if Scheer hadn’t said anything out of the ordinary. Liberals took note and, soon enough, were taking aim. A few weeks later, in question period, the Liberal House leader, Ontario MP Bardish Chagger, tried changing the subject from the SNC-Lavalin affair by slamming Scheer for “attending the same rally as white supremacist Faith Goldy.” (The term “white supremacist,” rather than plain old “racist,” tends to feature in Liberal attempts to put Conservatives on the defensive.) That same day, Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen and Democratic Institutions Minister Karina Gould offered reporters variations on the theme.

It was plainly an orchestrated line of attack, and Conservatives are braced for much more of the same. With the Liberals slumping badly in early spring polls, they’ll be even more determined to exploit Scheer’s vulnerabilities—no matter how sensitive the subject matter—in the run-up to the fall election. Federal Conservative strategists tracked the recent Alberta election closely for insights into how Jason Kenney’s United Conservative Party won handily, despite facing a string of revelations that put the UCP on the defensive over charges of racism, homophobia and other strains of intolerance.

Those salvos weren’t enough to undermine Kenney among those voters primed to revert, after a brief experiment with an NDP government, to their Conservative tradition. The federal landscape, however, poses a tougher test, as the 2015 election proved. In that campaign, Stephen Harper’s Tories collapsed in key battlegrounds, notably Toronto and Vancouver suburbs, after pushing policies that, taken together, alarmed many voters—from banning veils at citizenship ceremonies, to stripping Canadian citizenship from dual nationals convicted of terrorism offences, to setting up a so-called “barbaric cultural practices” tip line to the RCMP.

After Trudeau’s Liberals swept those seats on their way to winning a majority, former Harper immigration minister Chris Alexander, who lost his own Ontario riding, said the impression that the Conservatives were “somehow an unwelcoming party” wasn’t fair. “But in political terms,” Alexander concluded, “it was a disaster.” As Scheer’s Conservatives strive now to keep Trudeau’s handling of the SNC-Lavalin affair front and centre, they know the Liberals will exploit any chance to reactivate voter suspicions about right-wing intolerance. So, when Chagger flung Goldy’s name at Scheer when he was on the attack over SNC-Lavalin, he was ready to rail back, “This is nothing but a disgusting attempt to deflect from their own despicable handling of this corruption affair.”

Scheer did choose to address the United We Roll rally, though, and senior Conservatives don’t deny that the crowd included some outright racists. “Did it turn out there were some bad apples there? Yes. But I don’t believe that somebody speaking out at an event they didn’t organize is responsible for the views of every single person in the crowd,” said Hamish Marshall, the strategist who led Scheer’s stealthily successful run for the party leadership in 2017, and who is now installed as national director of this year’s Conservative campaign.

Of course, Marshall is right that no politician can reasonably be asked to answer for every wingnut who turns up at a public event. Still, Scheer might have thought twice, given the way he’s opened himself up to unwanted scrutiny in the past.

When he was running for the Conservative leadership in the spring of 2017, he was interviewed by Goldy on her Rebel Media show. A few months later, after he won, Scheer declared that he wouldn’t talk to Rebel anymore after Goldy’s reporting from a notorious neo-Nazi gathering in Charlottesville, Va., crossed the line, as he put it, “between reporting the facts and giving those groups a platform.” That was awkward, since Marshall—a close friend of Scheer’s, and his main strategist—was a Rebel board member. He severed those ties, and told Maclean’s he had never been involved with Rebel editorial decision-making, only “web aspects of the business from a tech perspective.”

On the asylum-seekers issue—a core preoccupation at the United We Roll rally—Scheer’s Conservatives have, at best, stumbled in their messaging. They circulated an ad on social media last summer that depicted a black man rolling a suitcase up to a hole in a fence. The party quickly withdrew the image after it sparked outrage. As the convoy crossed the country, Scheer had to have heard that it was stoking ugly anti-migrant sentiment. Controversy swirled around the loosely organized yellow vest contingent—ostensibly inspired by protests in France that were sparked by outrage over fuel taxes. In Canada, many who identify with the yellow vest as a symbol are fixated on asylum-seekers entering Canada from the U.S.

Glen Carritt, a town councillor and owner of an oil-field services company in Innisfail, Alta., who was the convoy’s chief organizer, said a few weeks after the Parliament Hill rally that he wished he had kept its focus on pipelines and the carbon tax, and away from immigration. “Let’s put it this way,” Carritt said. “If I were to do it again, I think we’d have a more concentrated message. I learned a lot.” As for the yellow vest groups, he bluntly suggested that they pack it in. “In my opinion,” he said, “I think that whole movement needs to just stop, because it’s not working. It’s got a negative connotation.”

READ: The moral cowardice of Canadian media is leaving racism unchallenged

And then there was Goldy. “First of all, she wasn’t allowed at our event,” Carritt said with an air of exasperation. “She actually got onto an impromptu stage that wasn’t in our permit area. I want to be clear that she was not invited and did not speak on our stage.” Marshall has a similar view.“If Faith Goldy had been on the program, of course Mr. Scheer wouldn’t have gone anywhere near it,” he said. “She jumps up on a flatbed truck a half-hour after he leaves—it’s like saying if somebody walks into a restaurant a half-hour after you leave, you’ve had dinner with them.”

In other cases, Marshall claimed, Scheer is unfairly criticized. After the terrorist attacks in New Zealand in March, for example, Scheer tweeted initially that “peaceful worshippers” had been targeted, and was faulted by the National Council of Canadian Muslims, among others, for not specifying that those killed were Muslims at prayer in mosques. “Well, you know, [Public Safety Minister] Ralph Goodale’s first tweet didn’t mention Muslims, [Governor General] Julie Payette’s first tweet didn’t mention Muslims, the Queen’s first tweet didn’t mention Muslims,” Marshall said.

In a fiery speech in the House after the New Zealand attacks, Trudeau issued his clearest notice to date that he doesn’t plan to hold back this year on making racism an issue. “Toxic rhetoric has broken into the mainstream. It’s anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, anti-black, anti-Indigenous, misogynistic, homophobic,” he said, later adding, “The problem is not only that politicians routinely fail to denounce this hatred. It’s that, in too many cases, they actively court those who spread it.”

The danger of being seen as courting noxious supporters is a long-standing worry for right-of-centre politicians. Preston Manning, the former Reform party leader who has attained éminence grise status among Prairie populists, has argued that it is the “Achilles heel” of the conservative movement. “Is not its greatest weakness,” Manning asked in a 2013 speech, “intemperate and ill-considered remarks by those who . . . in fits of carelessness or zealousness, say things that discredit the family as a whole, in particular conservative governments, parties and campaigns?”

Defending against candidates and operatives who blurt out hateful comments requires organizational diligence. In the age of social media, that means laboriously combing through thousands of past Twitter missives and Facebook posts from would-be Conservative candidates. “I’ve got two full-time people at party headquarters doing nothing but that,” Marshall said, then corrected himself: “Two and a half—we just hired a part-timer as well.”

He insisted this isn’t a vulnerability unique to Conservatives, pointing out that Trudeau had to jettison the Liberal candidate in a British Columbia by-election earlier this year, after she tried to cast the contest in terms of rival ethnic voting blocs.

But Scheer’s challenge goes beyond needing to vet candidates more carefully than ever. Late last year, he came out strongly against that UN migration pact. In a statement laced with ominous rhetoric, Scheer said, “It attempts to influence how our free and independent media report on immigration issues, and it could open the door to foreign bureaucrats telling Canada how to manage our borders. Canadians, and Canadians alone, should make decisions on who comes in our country and under what circumstances.”

In fact, the UN agreement is a non-binding, unenforceable framework for international co-operation on coping with migrants, mostly on innocuous matters like collecting and sharing data on migrants, standardizing documentation and recognizing migrants’ qualifications and skills. Yet it has been turned into a stalking horse for paranoid attacks from the right.

In an interview, Immigration Minister Hussen, who came to Canada as a refugee from Somalia, equated Scheer’s take on the pact with the way it has been portrayed by fringe voices on the racist right. “Stuff that you used to read on the most far-right conspiracy websites, he was spouting in front of mainstream media,” Hussen told Maclean’s. He speculated that Conservatives might have made a strategic calculation that opposing the pact would “kind of steal support” from Maxime Bernier, the former Tory MP who broke away last year to launch the People’s Party of Canada (PPC), which takes a hard line against what Bernier calls “extreme multiculturalism.” (Recent polls have the PPC barely registering any support.)

For all their criticism of Scheer, the Liberals have signalled that they are also worried about appearing soft on migrants. Since stories of asylum-seekers crossing into Canada from the U.S. broke in 2017, about 40,000 have made their way into Canada between official border checkpoints. In a measure tucked into its 2019 budget omnibus bill, the Trudeau government tightened the rules so that migrants who had previously filed a refugee claim in the U.S. wouldn’t be allowed to apply again in Canada. The move stunned many Canadian immigration lawyers. But Hussen defended the measure. He said the UN rates the U.S. refugee determination system highly. “As long as that’s the case, I can rest assured that a person who claimed asylum in the United States is getting a fair shake,” he said. “We clearly said that if you don’t need protection from our asylum system, don’t clog it, don’t use it.”

Conservatives protest, with credibility, that if they had spoken of refugees needlessly clogging the Canadian system, or accused them, in the phrase used by Border Security Minister Bill Blair, of “asylum shopping,” Liberals would have denounced them for demonizing migrants. “Justin Trudeau has created this environment in Canada where we can’t talk about public policy related to immigration anymore because of all of his accusations of racism for political gain,” said Conservative MP Michelle Rempel, Scheer’s immigration critic.

It should be possible to critique immigration policy without being accused of racism. But there’s no denying—in the age of Donald Trump and of anti-migrant populism across Europe—that racism is a powerful undercurrent whenever immigration is debated. And in Canada, polling data shows it’s far more pronounced on the right of the political spectrum.

Arguably this year’s most widely discussed Canadian public-opinion finding came out early this spring from veteran pollster Frank Graves, the head of Ekos Research. Graves found that the segment of Canadians who think there are too many non-white newcomers is holding steady at around 40 per cent in recent years. What’s changed, however, is the partisan dimension in that data. In 2013, about 47 per cent of Conservative supporters and 34 per cent of Liberals told Ekos that too many immigrants were visible minorities. By this year, that gap had widened dramatically, to 69 per cent of Conservatives and just 15 per cent of Liberals.

Conservatives tend to roll their eyes at the mere mention of Graves’s name. He makes no secret of his progressive values and uses any chance he gets to sound the alarm about the rise of what he calls “ordered populism,” his term for the pervasive discontent that underpins everything from the rise of Trump to the Brexit forces in Britain to Bernier’s splinter party. Graves relates all those manifestations of populism closely to middle-class income stagnation and growing economic inequality. “If you think it’s problematic, as I do, then you have to focus on those [causes] rather than simply offering up the moral critique—‘Well, you’re a racist’ or ‘You’re a Nazi’—which doesn’t help much,” he said in an interview.

Rather than viewing the backlash against asylum-seekers in isolation, he sees it as part of a wider rejection of policies promoted or defended by experts from institutions like government and academia—the elite. Graves said his polling shows that the voters who don’t believe the immigration system is working, for example, also don’t believe a carbon tax is a plausible response to climate change.

If Graves is right, then the hottest hot-button issue in federal politics—racism—has to be seen as part of a broader rejection of politicians identified with elites. Yet it tends to be singled out, or lumped together with other forms of intolerance like misogyny, homophobia and anti-Islamic prejudice.

The recent Alberta election served as a laboratory for how all this can play out in contemporary Canadian politics, albeit with a uniquely Albertan twist.

Long before the campaign began, then premier Rachel Notley’s NDP had telegraphed that homing in on hateful remarks in Kenney’s UCP ranks would be a key campaign tactic. In the months leading up to the election, the NDP effectively forced Kenney to block several would-be candidates from running because of their unseemly social media histories. A few would-be MLAs were revealed to have made Islamophobic comments. Another showed an openness to an extreme anti-immigrant group called Soldiers of Odin. A former Kenney campaigner turned out to be involved with a white nationalist memorabilia e-store—and Kenney turfed him from the UCP altogether.

At her very first campaign event, Notley left no doubt this would be a major NDP line of attack. “Let me just say this: I personally do not believe that Jason Kenney is racist,” she declared in front of a human wall of candidates, NDP supporters and children. “But I do believe the UCP, as a party, has a problem with racism.”

She had fresh impetus for this assertion. On the eve of her writ drop, UCP candidate Caylan Ford resigned after PressProgress, a “media project” run by the NDP-aligned Broadbent Institute, released private messages from her that appeared to convey white-nationalist leanings. Ford stepped down to avoid being a “distraction” for her party. She would later decry the allegations as stemming from out-of-context messages leaked maliciously by a former friend. Kenney curtly condemned her remarks, but also bemoaned a “fear and smear” campaign from his rivals.

READ: Can Alberta stay conservative enough for Jason Kenney?

The allegations kept coming. Calgary UCP candidate Eva Kiryakos also dropped out, due to deleted tweets and Facebook comments showing prejudice against Muslims, trans people and gay-straight alliances. Days before the leaders’ debate, fresh revelations targeted a sitting MLA—the party’s education critic Mark Smith. In audio clips that surfaced from a 2013 church sermon, Smith equated homosexuality and pedophilia. He apologized, but to quit that late in the campaign would have meant forfeiting his rural seat.

The UCP ran on an immigration-friendly platform and Kenney was, as a key figure in Harper’s government, both federal immigration minister and the driving force behind Conservative outreach to ethnic voters. Charges of homophobia were arguably more damaging, since they were easier to connect to the UCP’s campaign pledge to roll back some Notley-approved protections for LGBTQ students. As well, Kenney’s early political activism included campaigning against gay spousal rights—a bit of personal history the NDP emphasized heavily.

In a race dominated by the economy, Notley never let up on urging Albertans not to shrug off extremist views from Kenney’s camp. “Don’t look away,” she said repeatedly in speeches toward the campaign’s end.

Yet Alberta’s election results show all that didn’t tip the scales—or at least didn’t make diversity and LGBTQ issues the ballot-box question for enough voters to save Notley’s government. Dimitri Pantazopoulos, a senior campaign advisor to Kenney, said the NDP used character assassination to distract from its own record and handling of the economic and pipeline files. “This other stuff was just bullshit sideshow stuff,” he told Maclean’s. “To sit here and dwell on these things really highlights how petulant politics has become in Canada.”

New Democrats don’t view their efforts as a complete failure. The UCP were eyeing a near sweep of the province and to take several seats in Edmonton, but Kenney only turned one seat blue in Notley’s orange fortress city. “I’d say the result solidified Notley’s base [and] made it very difficult for progressive-minded people to hold their noses and vote for Mr. Kenney,” said one senior NDP campaigner.

Like Hamish Marshall, Kenney acknowledged the crucial importance of candidate vetting, claiming that his party has one of the most stringent processes in Canadian politics. The UCP’s screening process included, according to the CBC, a 44-page questionnaire that asked if candidates had ever posted racist comments online or texted nude pictures. Maclean’s has learned all would-be candidates were instructed to friend on Facebook a made-up character named “Josh Brooks”—a UCP account used to track politicians’ social media activity.

It turned out that Josh couldn’t catch everything. With Caylan Ford, for instance, there was no way UCP screeners could track her private messages. With Eva Kiryakos, the party believes that the controversial accounts were deleted before she registered to run, although some rival Conservatives snatched the rogue comments earlier and circulated them. As for Mark Smith, his anti-gay commentary was part of a guest sermon. Its existence caught Conservatives by surprise. “It doesn’t matter how deep your vetting is, you’re going to miss things,” says one senior UCP organizer.

Brock Harrison, Scheer’s director of communications, spent the last few days of the Alberta campaign with the UCP team to pick up valuable experience. Kenney aides impressed upon him that he must figure out how to respond and manage the problems that will inevitably come up.

If Alberta was a telling dry run, the 2019 federal campaign will no doubt be rife with allegations. Marshall claims that expectation has less to do with Conservative vulnerability than with Liberal desperation. “I think the Alberta result sort of puts it in perspective,” he said. “There are things that candidates from all parties at various points in the past have said that might be offensive and disqualify them from being members of Parliament. But often what happens, and we saw this in Alberta, is the party that’s losing is lashing out, and simply saying everything, anything, that somebody said that is even slightly off a message track is immediately disqualifying or the end of the world.”

It is possible that charges of intolerance in the federal race will sound over the top to many voters, and they’ll ignore pleas—like Notley’s “don’t look away”—to take them seriously. But it’s also possible that Scheer’s image will be tainted if he keeps trying to harness the sort of anger that was on display at the United We Roll rally.

Channelling it might turn up his campaign’s emotional heat in a way that motivates many voters—or reveal a dark side that repels others. The toughest test of his leadership acumen might be whether he can give voice to that discontent without tipping over into sounding intolerant.

Harsh personal attacks are already the order of the day in Ottawa. In the wake of the SNC-Lavalin affair, the Conservatives released a 1½-minute video they called “Justin Trudeau vs. the Truth.” After the United We Roll rally, Trudeau repeatedly baited Scheer in the House by demanding that he explicitly “condemn white supremacist movements.” Few words in politics are more caustic than “liar,” but “racist” is one of them. The more often the former is heard in the run-up to the federal campaign, the more likely it becomes that Canadians will be hearing the latter, too.

This article appears in print in the June 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Target Andrew Scheer.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.