This is what’s wrong with Canada’s Right

As its support base shifts and hardens, the Conservatives increasingly have a new measure: are you with us or against us?

While his party has gone on the attack, Andrew Scheer has mostly stuck to his aw-shucks persona (Andre Forget/OLO)

Share

This month’s duelling cover stories go inside the angry, closed-minded, petty world of Canadian politics—and how to fix it. Here’s why we did it.

This month’s duelling cover stories go inside the angry, closed-minded, petty world of Canadian politics—and how to fix it. Here’s why we did it.

During Ontario’s Progressive Conservative leadership race last winter, Bill Fox donated to Caroline Mulroney’s campaign. The party immediately began carpet-bombing him with fundraising messages denouncing the “downtown elites” they were going to take down. “When you live in a condominium in Leslieville at the corner of Dundas and Carlaw, it’s pretty hard not to take that a little personally,” says Fox, hooting with laughter.

He was Brian Mulroney’s director of communications when Mulroney steered the PCs to a historic federal majority of 211 seats in 1984, but Fox hasn’t felt at home with the current federal Conservatives for years, mostly because of the party’s social policy and anti-elite bent. He can see the feeling is mutual. “In their mind, I am now part of the ‘other,’ ” he says. “I’m not them.”

The major parties in Canada were, not so long ago, big tents that were nominally blue or red but sheltered a broad and often ideologically mixed bag of policy positions and personal opinions. Every few years, they would cobble together a set of proposals tackling the issues of the day and hope to build a coalition large enough to govern. As Fox points out, in his days on the front lines, Red Tories like him and Blue Grits were common creatures, and if you wanted to be mischievous, you would ask what the difference was between them.

No one would confuse a Grit and a Tory of any hue these days, and it would be treated as a slur if you did.

On the right side of the Canadian spectrum, this tribalism has its roots in the 2003 merger of the PCs and Canadian Alliance that produced the Conservative Party of Canada, now led by Andrew Scheer. But, paradoxically, the newly split right—thanks to Maxime Bernier bolting to found the anti-immigration, libertarian People’s Party of Canada—is further fuelling the Conservative tendency to appeal to the most ardent base and seemingly no one else. “Mr. Bernier, for his own selfish reasons, has made it increasingly difficult, and borderline impossible, to campaign in the mould of the Harperite campaign strategy, which was ‘rough the edges off and go for a big-tent Conservative party,’ ” says Jason Lietaer, a conservative strategist and president of Enterprise Canada. “Because Mr. Scheer is fighting a rear-guard action, that is a significant risk.”

RELATED: Why it’s dangerous to equate the Left and the Right

More broadly, James Moore, Stephen Harper’s former industry minister, argues that across all parties, the traditional left-right axis has been replaced by a sort of tripartite purity test. “There’s ‘with us,’ ‘might be with us,’ and ‘against us,’ ” he says. “And it’s on an issue-by-issue basis.”

And the metrics by which Canadian Conservatives judge who is with them or against them have fundamentally shifted. University of Saskatchewan political studies professor David McGrane, drawing on findings of a paper he co-authored called “Moving beyond the urban/rural cleavage,” says the action on the right is on identity issues like immigration, gay rights and environmentalism rather than traditional small-government, low-tax policies. “For Conservative voters, suburbanites and people who live in more rural areas, this idea of being socially progressive and economically conservative doesn’t hold up,” he says. “You’re probably more economically progressive and socially conservative.”

This appears to have animated a Conservative voter base that is more hard-core in its partisanship than elsewhere along the spectrum. This fall, Abacus Data found that 31 per cent of Canadians would only consider voting for one party—of which 14 per cent were Conservative, 10 per cent Liberal and four per cent NDP. Of those inclined to vote Conservative, 47 per cent would not consider another party, compared to 30 per cent of Liberal supporters and 21 per cent of NDP voters.

In September, Ekos Research Associates Inc. asked Canadians which issue should be most important in the 2019 federal election. Fiscal issues like taxes and debt were the top concern of 46 per cent of Conservative supporters, but just 20 per cent of Liberal partisans, 12 per cent of NDP and seven per cent of Green supporters. Climate change and the environment, on the other hand, were the biggest worry for 43 per cent of Liberal voters, 47 per cent of NDP and 62 per cent of Green supporters—but just seven per cent of Tory voters consider that the defining issue. “There are two different worlds,” says Frank Graves, president of Ekos. “There’s no common ground. You don’t divide that and say, ‘Let’s meet in the middle.’ ”

Ekos’s numbers further show that Conservative supporters are less likely to see the #MeToo movement as necessary and overdue than other partisans; more likely to think discussions of racial and gender equality are distracting from more important issues such as the economy; and more inclined to say Canada is taking in too many immigrants. And there has been a shift in who those supporters are, with Ekos finding the Tories now hold an “overwhelming” advantage among the non-university-educated—a demographic split that did not exist during the 2015 federal election. “When did the Conservatives become working-class heroes?” Graves wonders. “This is a totally different political landscape.”

Graves’s research shows that right-leaning voters are increasingly attracted to what he calls an ordered populist outlook. They feel economically and culturally insecure, they’re often stuck in downward class mobility and they “value order and obedience more than creativity and reason.” They are often drawn to a nostalgic vision of an earlier period when things made more sense. “This is the new contest for the future: are we going to go for this ‘pull up the drawbridge,’ follow the way a lot of Europe is going, and Britain and the United States?” Graves says.

PAUL WELLS: Canada’s angry, divisive politics are as old as Canada itself

The paradox, he says, is that this shift within the right-leaning electorate runs counter to the long-standing trend of Canadians becoming more open on issues like immigration and trade. But the emotional intensity is on the side of the ordered populists. “There’s nobody out with placards going, ‘Bring more immigrants!’ ” Graves says.

A pair of recent papers based on the Canadian Election Study (CES), a massive national study conducted in each election year going back to 1965, traces how partisan attitudes have evolved in Canada.

Laura Stephenson, a political science professor who specializes in voter behaviour at Western University, co-authored a chapter in the 2017 book The Blueprint: Conservative Parties and Their Impact on Canadian Politics, examining how the views of right-leaning Canadians shifted between 1993 and 2011 as they were thrown together in a unified Conservative party.

Before the merger, PC and Reform/Canadian Alliance supporters largely agreed on economic issues, she and her co-author, Éric Bélanger of McGill University, found, but they were not on the same page on social issues such as attitudes toward women, immigrants and racial minorities, or constitutional questions like how much should be done for Quebec, or feelings of regional alienation. After the merger, that flipped so that Conservative partisans had varying views of economic matters but aligned more on other issues, they found—with two exceptions. Regional alienation remained a point of contention, perhaps reflecting the gaps between old Reformers from the west and new Tories from other provinces, and moral traditionalism was another point of tension. To Stephenson, the present Conservative party is clearly socially conservative, as a result of its Reform and Canadian Alliance DNA. “There is no other game in town on the right—if you’re a conservative in any way, you either have to plug your nose and swallow the social conservatism or go elsewhere, and then you have to deal with the economic,” she says. “The fact that there’s only one party on the right gives it a little bit of leeway in terms of what it can do, but I think moral issues are also ones that clearly divide people who do support the Conservative party.” That potential for division was reflected in Harper’s refusal to reopen the abortion debate, she notes.

A second paper based on the CES, co-authored by Stuart Soroka, a political science professor at the University of Michigan, examined “partisan sorting” in Canada. The term refers to whether people who hold certain views increasingly find their way to a particular party over time, so that, for instance, people who are in favour of immigration may identify more strongly with the Liberals, while those who are not will find their way to the Conservatives as that issue becomes more important to them. That concept is distinct from but related to polarization, which refers to the attitudes of people on certain issues getting further apart over time.

ANDREW MACDOUGALL: The question Conservatives need to answer before they say anything

Soroka and his co-author, Anthony Kevins of Utrecht University, focused on 1992 to 2015, examining people’s attitudes toward the welfare state—such as whether the government should “see to it that everyone has a decent standard of living” or “leave people to get ahead on their own”—and testing how much of the variation in opinion could be predicted based on someone’s party. “What our analyses suggest is that over time, I can explain that variation better and better and better just by using party,” he says.

Similarly, for a long time in Canada, you wouldn’t be able to predict which party someone voted for based solely on their preferences about immigration, but other research Soroka has yet to publish shows that changed around 2006 (an election year that saw Harper defeat Paul Martin’s Liberals). “It was the reformation of the Conservative party as the not-Red-Tory party, as a more traditional conservative party,” he says of the turning point.

Partisan sorting on its own is neither a good or a bad thing, Soroka says. There is clarity and simplicity in voters having coherent platforms to choose from, but on the other hand, it’s not very efficient to have public policy that swerves wildly from one set of priorities to another depending on who is in power.

Polarization, however, is not neutral. In a polarized electorate, people are so divided that they see the two different worlds that Graves has identified in his research, and that makes democratic politics complicated and dysfunctional, Soroka says. Sorting is a step along the way to polarization. “I wouldn’t argue that Canada doesn’t have to worry because it’s only partisan sorting at this point,” he says. “Once you get people into more like-minded groups, once you make it clear to people who their team is, then they can start to see bigger differences.”

JEN GERSON: How to harness the volatility of the populist right

The politics-as-team-sport mentality is prominent in the issues and approach that have preoccupied the right side of the Canadian spectrum of late. The Tories have a flair for displaying a catty edge on social media, with MPs Michelle Rempel and Pierre Poilievre alternately playing concern trolls or outright attack dogs, and Scheer himself appearing to be A/B testing Smiley Suburban Dad Who Just Happens to Lead the Conservative Party. In recent months, the party established two websites devoted to providing mocking one-note commentary on the Liberal government: the budget-focused IsItBalancedYet.ca and IsJustinTrudeauOnVacation.ca, which is now defunct and redirects visitors to the main Conservative party page.

The Conservatives and their Ontario PC cousins who wield outsize influence on the national stage right now spent much of the summer and fall arguing that the Liberal government was directly responsible for thousands of migrants crossing the border illegally from the U.S. In July, the federal party produced an attack ad that showed a dark-skinned man towing a suitcase through a gap in a fence, using Trudeau’s infamous tweet welcoming newcomers to Canada as a bridge. “Trudeau’s holier-than-thou tweet causes migrant crisis—now he needs to fix what he started,” the ad copy read. It was pulled after a barrage of criticism. And in early December, Scheer denounced Canada’s participation in the UN Global Compact on Migration. “It gives influence over Canada’s immigration system to foreign entities,” he warned. The agreement is non-binding and would do no such thing—a fact immediately pointed out by Harper’s former immigration minister, Chris Alexander.

But it’s the carbon tax that has been the most focused and furious battleground. “The Trudeaus of the world seem out of touch in what they’re saying,” says Lietaer. “Most people, as well, are looking at it and saying, ‘If you really think me paying a couple cents more per litre of gas is going to save the world, I think you’d better come up with a new plan.’ ” The carbon tax is about affordability, and oblivious elites who expect ordinary people with normal budgets to shell out even more, but like most every other political issue right now, it is a proxy for something much larger than itself. “The same people who told me that globalization and information technology were going to float us on an infinite cloud of prosperity are the same ones who have told me we’ve got to deal with climate change, and look where that got us,” Graves says, by way of explaining the resistance on this.

ANNE KINGSTON: The political terms ‘right’ and ‘left’ are simplistic, damaging, and need to be retired

Doug Ford and the Ontario PCs capitalized on this last spring, trouncing Kathleen Wynne’s Liberals with an explicit “stick it to the elites” campaign. David Herle, who ran Wynne’s campaign, says his team spent more than two years trying to address affordability worries, but they could have mulled it over for years longer and they never would have come up with the things the Ford campaign offered. “It’s not like we missed that issue,” Herle says, mentioning pensions, guaranteed income pilots and raising the minimum wage as examples of the Wynne government’s attempts to address it. “That stuff was all very popular, but it was seemingly just as effective to promise to lower the gas tax by 10 cents and to promise buck-a-beer and to really take this down to a simplistic level.” It’s telling that what proved popular with conservative voters were gestures that served virtually no pragmatic purpose, but carried note-perfect symbolic meaning.

To Herle, Conservatives are working from a fundamentally different playbook than the “let’s see how popular we can be” instincts of the Liberal party over the past decade. The Tories are less interested in gaining new supporters or wooing tentative ones, he argues, and are instead focused on firing up their most ardent base. “So let’s have a really hard, direct, motivating message to our supporters, on the theory that if they turn out to vote, and those unmotivated people who are kinda Liberals don’t turn out to vote, we’ll win the election,” he says. Herle doesn’t believe Canadians at large are terribly worked up about illegal border crossers or the carbon tax—but they’re perfect issues for stoking the Tory base. “They’d rather have 30 per cent solid supporters than 45 per cent wishy-washy supporters,” he says.

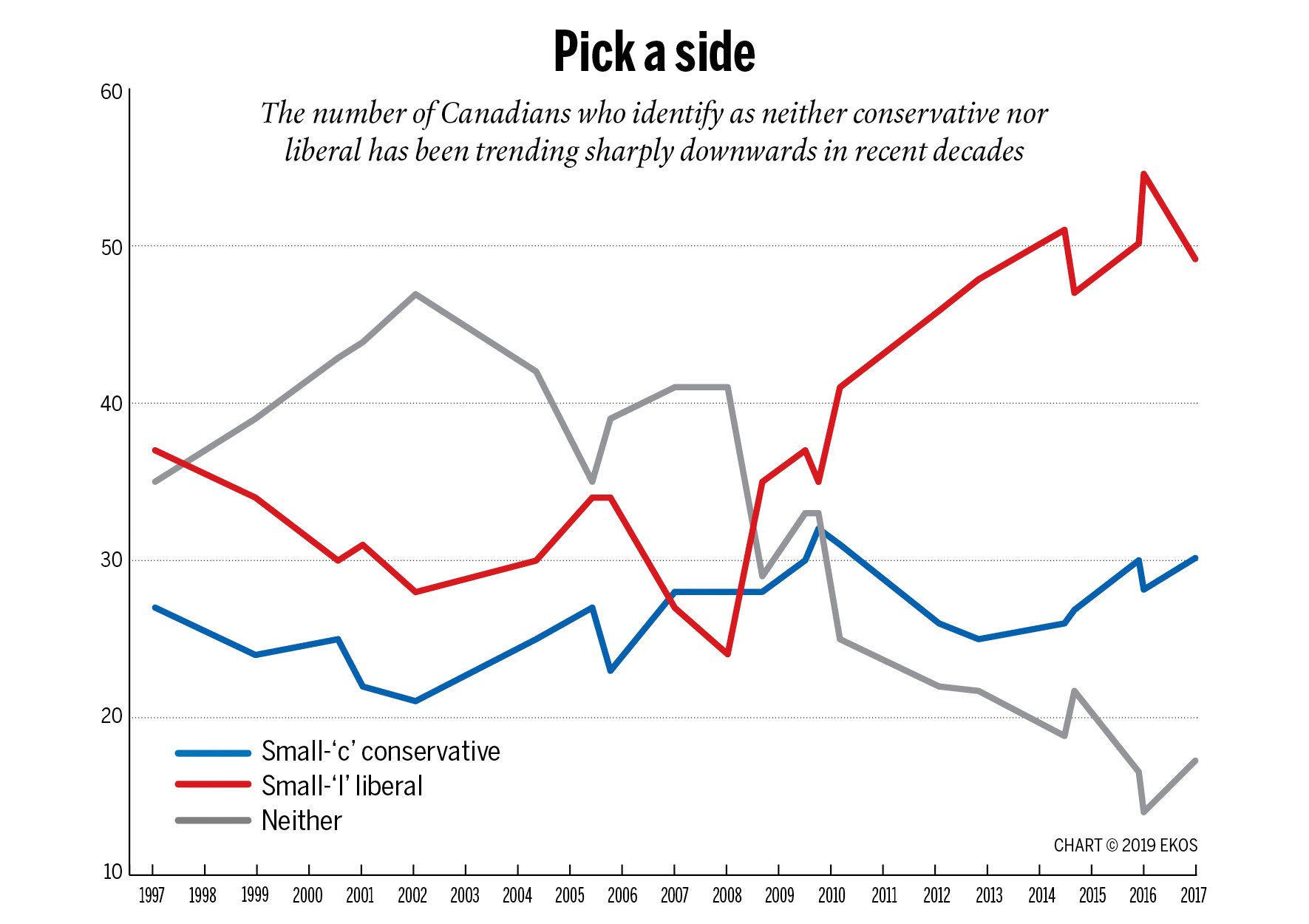

Polling suggests that, increasingly, Canadians see themselves as explicitly choosing one team or another. Ekos asks whether people consider themselves small-“l” liberals or small-“c” conservatives, independent of who they vote for in a given moment. From 1997 to 2008, “neither” was the most popular choice, but since then, the ranks of the unaffiliated have taken a nosedive, from a peak of 47 per cent in 2002 to just 17 per cent in 2017, when 30 per cent declared themselves conservative and 49 per cent liberal.

Moore, the former Harper cabinet minister, has a theory about the tribalism of contemporary politics. He takes a page from Harvard professor Robert Putnam’s 2001 book, Bowling Alone, which used disappearing bowling leagues as a vehicle to examine the isolation of modern life. Volunteer involvement, charitable giving and participation in religious organizations have plummeted, Moore points out, and more of us live alone than ever before. And while we warm our hands and our internal rage-engines around the hearth of social media, that makes us even more isolated in real-world ways.

Moore argues that people have plugged politics into the place in our lives and sense of self that used to be occupied by a much deeper set of attachments. “They’re investing their religious energy, their ideological energy, their sense of community, their sense of belonging, their sense of aspiration, their need for expression of frustration—all of it is getting dumped into politics,” he says. People build themselves digital echo chambers and read opinions they already agree with that are more articulate than their own internal dialogue, Moore says, and that gets dark really fast because we were never meant to define the entirety of who we are by who we vote for.

“It’s too much,” he says. “Politics can’t handle it. It’s more than what politics was made for.”

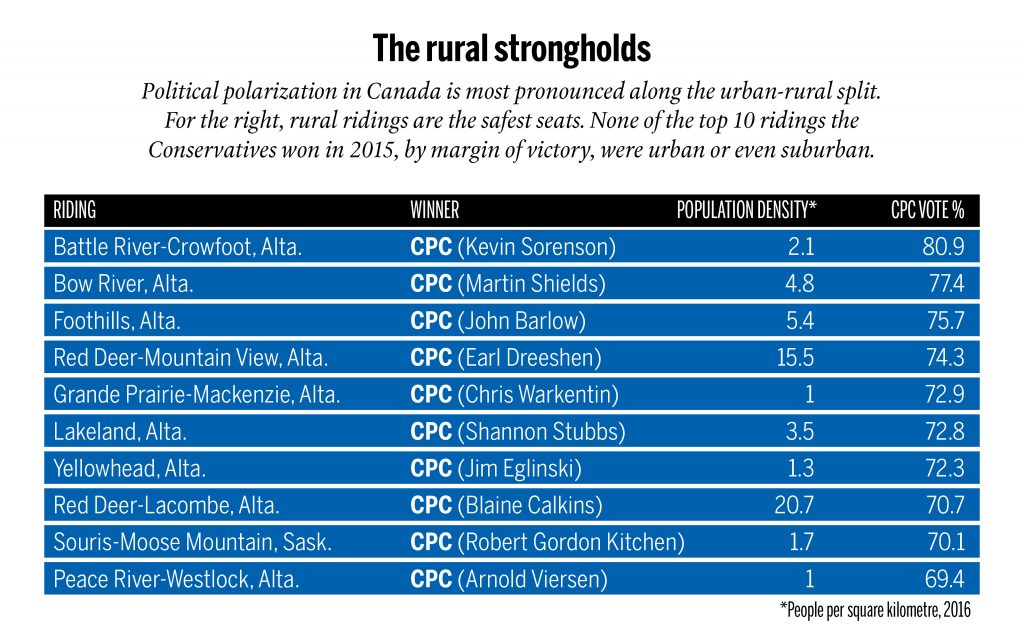

CORRECTION, Feb. 6, 2019: A previous version of a graphic in this story claimed the riding of Souris-Moose Mountain was in Manitoba. In fact, it is in Saskatchewan.

MORE ON WHAT’S WRONG WITH THE LEFT:

- TERRY GLAVIN: What the yellow vests’ revolt revealed about the sad state of the Left

- ANDRAY DOMISE: The Left is constantly trying to out-woke itself. That’s a problem.

- ANNE KINGSTON: The political terms ‘right’ and ‘left’ are simplistic, damaging, and need to be retired

- POLL: Canada’s most polarized voters really, really hate Trudeau