Why Canadian baby boomers gave up on hitchhiking

Peter Shawn Taylor explains the rise and fall of the golden—and federally funded—age of hitchhiking

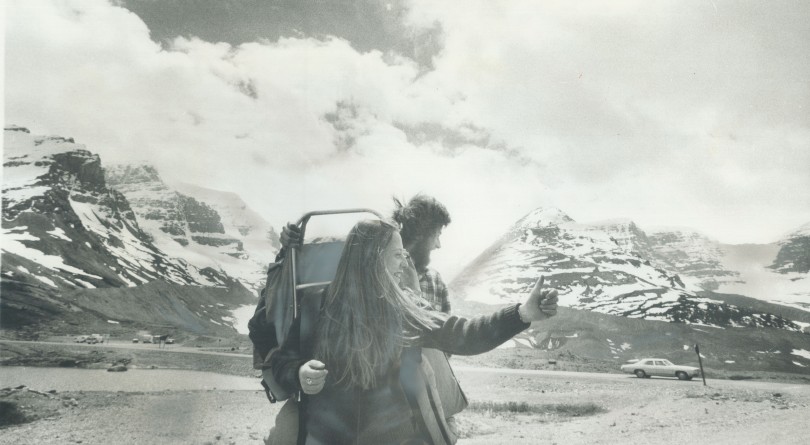

Anne Saulnier (R) and her husband Brian prepare to give a ride to the anthropomorphic robot named hitchBOT on Highway 102 outside of Halifax, Nova Scotia, July 27, 2014. The hitch hiking robot is part of a social experiment to see if strangers will help hitchBOT complete its 6,000 kilometer journey from Halifax to Victoria, British Columbia. (Paul Darrow/Reuters)

Share

Along with the rest of the country, you probably fell in love with hitchBOT, the world’s first hitchhiking robot, back in the summer of 2014.

The brainchild of academics David Harris Smith of McMaster University and Frauke Zeller of Ryerson University, hitchBOT set off from Halifax on a cross-country adventure toward Victoria. Lacking motive power, superintelligence or a death ray, this robot relied solely on its “digital” thumb to snag rides from friendly passersby. Like the legions of human hitchhikers who once blanketed Canada’s highways, hitchBOT was propelled by the charity of strangers who happened to be going its way.

HitchBOT made the 10,000-km, 19-ride journey in just 26 days. Along the way, it stirred up plenty of media attention, as well as nostalgia for the golden era of Canadian hitchhiking in the 1960s and ’70s. There were a few anecdote-worthy escapades along the way, including the time it was dropped on the dance floor at a wedding reception. But it arrived in B.C. safely and in one piece.

Later, America beckoned. Now something of a media celebrity, in July 2015 hitchBOT set off from Salem, Mass., for San Francisco. Two weeks later, however, the journey came to an abrupt end. Someone in Philadelphia, presumably lacking in nostalgia and charity, ripped open hitchBOT’s head and stole the electronics. Its travelling days over, hitchBOT has since found a home at the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa.

Aside from a cautionary tale about visiting Philadelphia, the story arc of hitchBOT can also be seen as a miniature version of the broader history of hitchhiking itself. It too started off as a romantic notion that quickly turned into a cultural phenomenon. And while it was a great adventure while it lasted, one bad ride put an end to all the fun. Now it’s a museum piece.

“We all used to hitchhike when I was growing up in Saskatchewan during the early 1970s. It’s just what everybody did,” recalls Linda Mahood, 57. A history professor at the University of Guelph, Mahood is the author of the forthcoming book Thumbing a Ride: Hitchhikers, Hostels and Counterculture in Canada, which examines the once-ubiquitous practice and its subsequent demise from numerous perspectives. “It was a means of local transportation, but it was also a bit of a rebellion as well,” she says. “There was something adventurous about accepting a ride from a stranger—it offered a thrill and the possibility of an interesting story at the end.”

While thumbing a ride has been around for as long as the car, a convergence of political, demographic and social factors meant that for a few glorious years, it was more than just a cheap way to get around. It became a rite of passage and a symbol of the times.

Young men and women could amble down to the side of the road, stick out a thumb and head off on a journey toward peace, love and universal understanding. “For a while, there was a real excitement about hitchhiking,” says Mahood. “Youth were heading out on the open road, adults were stopping to pick them up. Everyone was getting something out of it. It was a very communal time.”

How popular was hitchhiking during this golden era? Anecdotes abound that there were sometimes more thumbs than cars on the road. Reliable statistics are harder to come by, but media reports estimated that 50,000 to 100,000 hitchhikers passed through Winnipeg every year between 1970 and 1975. In 1971, the Vancouver Sun declared that “hitchhiking has become a national phenomenon.”

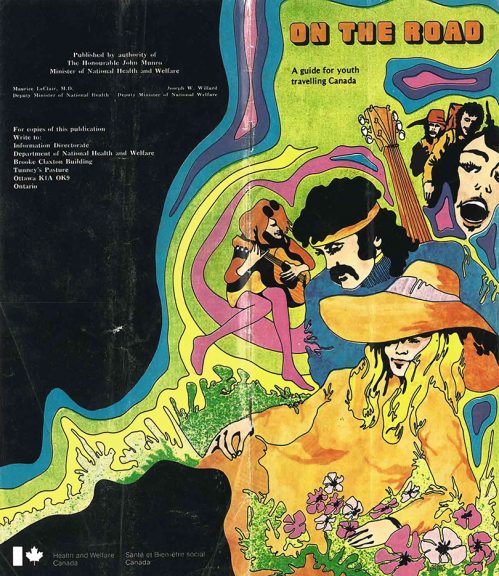

Perhaps the most convincing evidence of hitchhiking’s significance is how it captured the attention of politicians. A youth-friendly prime minister Pierre Trudeau once threw himself at hitchhiking with the same verve his son now displays for legalized marijuana. In 1970, for example, the federal government created a cross-country chain of 40 hostels, some located in unused military barracks, offering free lodgings for young hitchhikers. The next year, a series of kiosks shaped like giant teepees dotted the Trans-Canada Highway to provide weary hitchhikers with water, advice and phone calls, also at federal taxpayers’ expense. Ottawa even distributed a pamphlet titled On the Road, with tips on how to make a successful cross-country trek: “Carry a large sign if you are trying to flag someone down . . . Don’t hitchhike on a bridge.”

“It seems a bit nuts today,” admits Mahood. “But this was a time of high youth unemployment, so the Trudeau government decided it would make hitchhiking across the country seem like the equivalent of having a job. It was a way to co-opt the youth movement.”

Hitchhiking quickly became a travelling embodiment of Baby Boomer ideals, observes Doug Owram, history professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia and author of Born at the Right Time: A History of the Baby Boom Generation. “The idea was that you would meet groovy people, see the country and do it in a non-material way, which was appropriate from both an ideological and pocketbook perspective,” he notes.

Even technology seemed aligned with broader political and social urges; cars in the early 1970s were often outlandishly cavernous and well-suited to giving free rides to strangers. Above all, says Owram, “hitchhiking reflected a certain naive trust in the goodness of people—that they would be interesting rather than dangerous.” Like free love, however, the era of free rides proved unstable.

A riot at a federally run hostel in Vancouver eventually convinced Ottawa to get out of the free accommodation business. Those teepees along the Trans-Canada Highway had a disturbing habit of blowing over in stiff Prairie breezes. Even the groovy On the Road pamphlet was criticized for being full of mistakes.

Of even greater significance was a shift in how the public regarded the risks of hitchhiking, especially for young women. While early media coverage focused on the freedom of young Jack and Jill Kerouacs as they traipsed across the continent, “by the mid 1970s you couldn’t pick up a newspaper without reading another horrifying story about hitchhiking gone bad,” notes Mahood. “There was something about a girl hitchhiking alone that really started to alarm society.” A typical mid ’70s headline: “Toronto hitchhikers: three raped at knifepoint.” Movies and television outdid themselves with grisly tales of the consequences of accepting, or offering, rides with strangers. Governments quickly ditched their how-to advice and began actively discouraging the practice.

While the overwhelming majority of hitchhikers made it home suffering from little more than the usual irritations of weather, bugs and “dead zones”—stretches of road where rides were scarce—the notion that hitchhiking had become a foolish and unnecessary risk had taken a firm hold on the public consciousness by the 1980s, and still persists today. Now you can drive for days in many parts of Canada without seeing an outstretched thumb. “There are fewer hitchhikers than there used to be, no doubt about it,” says assistant commissioner Eric Stubbs of the RCMP’s B.C. headquarters in Surrey, a 26-year veteran of the Mounties. The reason? “It’s risky. The glamour and romance of it has passed us by in a significant way.”

But is hitchhiking any riskier now than it was in the 1960s and 1970s, when everyone was doing it?

Given the lack of statistics, it’s impossible to say for sure. Mahood points to an intriguing academic study conducted during a Toronto transit strike in the 1970s that found the number of sexual assaults committed against hitchhikers rose dramatically when the city’s subways and buses were out of service. However, the total number of sex crimes didn’t change—suggesting hitchhiking had no impact on the city-wide risk of sexual assault, although its popularity apparently drew the attention of existing predators. Whether hitchhiking became riskier or whether public opinion simply shifted, the practice lost its social currency and disappeared from view. Intriguingly, the rise and fall of hitchhiking culture—late 1960s to mid 1980s—neatly corresponds with the trajectory of Baby Boomers hitting their early 20s, the age when the quest for adventure runs hottest. “At the end of the day, it was probably just a Baby Boomer experience,” says Mahood. And it ended when all those risk-taking Baby Boomers, thrill-seekers who once willingly hopped into cars with strangers, grew up to become overprotective helicopter parents unwilling to let their kids take the same risks they once did. Who killed hitchhiking? The same folks who gave it life in the first place.

Of course, the notion of unstructured journeys as the means to adventure and a rite of passage into adulthood still holds appeal for many young Canadians. But cheap air travel to Europe and Asia and ride-sharing apps now make it possible to have those experiences without the need to stand by the side of the road in the rain. Even the budget travel guide Let’s Go has long since retired its famous thumb logo.

There are a few places in Canada where hitchhiking remains a common sight, but more often out of necessity than choice. In many of the 18 unsolved missing or murdered women cases associated with northern B.C.’s Highway of Tears, the women were last seen hitchhiking due to a lack of cheap transportation. “The people hitchhiking in northern B.C. are doing it because they have to, not out of any sense of adventure,” says Stubbs. “It’s a need to get from A to B.” In response to outcry over the Highway of Tears, Mounties are now instructed to offer rides to local hitchhikers who fit a victim profile. And the provincial government recently unveiled a new bus service for the area.

But while hitchhiking may be in broad retreat, that old longing for the freedom of the open road hasn’t been completely extinguished—at least not for a few remaining Boomer holdouts. Yrene Dee of Lumby, B.C., spent her younger days thumbing around the world, including a three-month tour of New Zealand with a six-year-old daughter in tow during the 1980s. Now, as she plans her retirement, Dee, who writes the Backcountry Canada Travel blog, is thinking about recapturing some of that old excitement with one more thumb-powered adventure, perhaps to the Canadian Arctic. “Back in my time, we just did it because it was fun and adventurous and because we didn’t have any money,” she says. “Now I want to do it to prove I still can.”

Dee is prepared to make a few concessions to changing habits, however. “The hardest part of hitchhiking is always getting out of town,” she says. “So this time around, I’ll probably carry a big sign. I might bring some pepper spray as well.”