An oral history of the first flight of Syrian refugees to Canada

An oral history of the first flight of Syrian refugees to Canada

A Canadian Armed Forces CC-150 Polaris lands at Toronto Pearson International Airport at 11:30 p.m. on Dec. 10, 2015. (Kenneth Allan/CBSA)

The first flight

On Dec. 10, 2015, the first plane of Syrian refugees landed in Toronto. One year later, these new Canadians and the people who helped them describe how it all happened.

By Michael Friscolanti and Aaron Hutchins

At last count, the Trudeau government has welcomed more than 34,000 Syrian refugees to Canada—but none received a more public reception than the 163 who arrived in Toronto aboard the first military airplane. One year later, Maclean’s interviewed nearly 50 people forever connected to that historic flight, from grateful passengers to the Canadian Forces pilot to the Iraqi translator—himself a new citizen—who helped the Prime Minister greet the refugees. This is their story, told in full for the first time.

Syrian refugees arrive at a hotel near Pearson International Airport in the early hours of Dec. 11, 2015. (Steve Russell/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

PART I: The ‘Jaws’ moment

Vanig Garabedian, 47, Syrian refugee: Some people have an image that refugees will be from a camp, that they will be poor, and that they will be uneducated. But that is not true. Being a refugee means you are persecuted in your country. I am a gynecologist and my wife is a hematologist. We left Syria in 2014 after my clinic was hit by rockets.

Ilia Alaji, 60, Syrian refugee: I didn’t want to leave. My family talked amongst ourselves: “Maybe tomorrow there will be peace, maybe next week.” But we couldn’t wait. We left everything there.

Talar Chitjian, 33, Syrian refugee: My husband and I got married on Aug. 23, 2014. While we were engaged, our wedding house was bombed. We rented another home for seven days after the wedding and then we fled the war. Several times I saw people dead, arms and legs here and there. Can you imagine?

Jirair Agigian, 33, Syrian refugee: I am from Latakia, but my family was living in Damascus. Every day I took my kids to school, and every day I heard bombs.

Natalie Boudakian, 27, Syrian refugee: I studied software engineering at the University of Aleppo. When I was in my fourth year, taking my first-semester exams, there were bombings at the university. Of course it was scary, but I so much wanted to graduate because I was afraid about what was going to happen to my credits. So I waited another year before leaving.

Kevork Jamkossian, 29, Syrian refugee: We left Aleppo in 2014 and moved to Lebanon. We ran a company in Syria, a plastics company. It was my father’s business. We lost everything when the war started.

Dawn Edlund, associate assistant deputy minister of operations at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC): In September 2015, I started working full-time on the Syria project. We had been working with the [Harper] government on what options there were for bringing Syrians to Canada, but after that photo went viral [of three-year-old Alan Kurdi, dead on a Turkish beach], the government wanted us to look at other options. They settled on bringing the same number they had previously promised—10,000 Syrians—but by September 2016 instead of December 2017. So the plan was to speed up the process by more than a year, and we started moving additional staff overseas.

Pierre King, senior operations officer, Beirut, International Organization for Migration (IOM): The Canadian embassy asked us to arrange a hotel because they were bringing in 10 additional officers. And then during the course of that first selection mission, the new Trudeau government said they were going to bring in 25,000 refugees by the end of the year. We just couldn’t believe it. I thought it would take a miracle.

Edlund: We all went, “Ooh, that’s a whole different number and a whole different time frame.” I have jokingly compared it to that moment in the movie Jaws, where the guy sees the great white shark for the first time and says, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.” The scale and scope of what we were asked to accomplish as Canadian public servants was unheard of.

Heidi Jurisic, director, Greater Toronto Area Immigration, IRCC: It was November when my boss said to me, “OK, we need to establish one operational lead at the director level in Toronto. Are you up for the challenge?” Without hesitation, I said, “Yes, whatever needs to be done”—not understanding what I was agreeing to do.

Wil MacMillan, director of the Integrated Operations Control Centre at Greater Toronto Airports Authority (GTAA): We knew from the election this was happening, and we started speculating. But on Nov. 10, that’s when we received notification that yes, the government is looking at using Pearson airport. The first thing we had to figure out was: Where will we conduct this operation?

Jurisic: It was the GTAA that came forward and said, “You know, we’ve got this terminal at Pearson that is not being used. We could stand it up and have this thing entirely dedicated to this project.”

MacMillan: We had what we call an IFT, an infield terminal. We built it as a temporary terminal to provide capacity while we were tearing down the old Terminal 1. It was designed for a short-term purpose, so it was just sitting there.

Dana Franzgrote, emergency management systems officer, aviation services, GTAA: It was a little bit worn down and needed some lipstick.

Jurisic: They literally brought us to the terminal and said, “This is it, guys.” It was ready enough that with some really quick action, including installation of some IT equipment and work stations, we could get the place up and running quickly enough.

MacMillan: It was a massive juggling act, but ops guys are adrenalin junkies. We kind of thrive off that. If you say, “Go sit at your desk and do the paperwork,” that’s not us.

Franzgrote: There was an overwhelming sense of: “Oh crap, this is such a large undertaking and we don’t have much time.” But the attitude became: “OK, let’s figure out how to make this happen.”

Jurisic: I work for the government. We’re a big bureaucracy, and our timelines when we plan things are much, much longer than what we had the luxury of having to get this project under way. It was the shortest timeframe imaginable, but there was never a doubt that we could get this done.

Bruce Grundison, senior director, resettlement operations, IRCC: The intensity of the planning effort was something I’d never experienced. I remember turning to a colleague and saying, “Something amazing is going to happen here. We have such an opportunity to participate in a historic effort—if we can pull this off.”

Sharon Chomyn speaks with Syrian refugees waiting to pass through security at Beirut International airport (Corporal Darcy Lefebvre/Canadian Forces Combat Camera)

PART II: ‘Showtime’

Sharon Chomyn, Lebanon project director, IRCC: There was a lot of pressure, obviously, and a lot of interest to get that first flight going. People back in Canada were very anxious to see the first arrival of refugees, and we were doing absolutely everything we could to get people through the process and ready for that first flight.

Edlund: We started to use the phrase “Syria time” to describe our days—not because we were all operating with no sleep, although that was part of it, but because every day seemed like it was a two-week period. There was just so much happening every single day.

Michelle Cameron, Canadian ambassador to Lebanon: I remember it being an absolute blur, a flurry of activity. We had over 150 extra staff in Beirut to help us with processing and interviewing, and we had partners, including the IOM [International Organization for Migration], helping us fill out forms and with logistics. And we were always reminding ourselves: “We are about to change not only these people’s lives, but the course of their families’ lives from here on.”

Edlund: There was an incredibly intricate dance with the Lebanese government when it came to getting exit permits for people. The permits are only good for a particular period of time, and so we had kind of a chicken-and-egg situation: we had to pick a date for the first flight, but we also had to have enough people with exit permits to get on that plane.

King: The Lebanese government wants to screen the people who are leaving, and normally a list had to be sent 18 days in advance. They kept on saying, “It’s for your own security. We’re trying to look for the bad people.”

Edlund: I remember saying to our deputy minister at the time, “We just have to pick a date, and if we end up with 25 people on the first flight or 150, we just have to pick a date or I can’t move it forward.”

Grundison: While the IOM was working to procure the charter flights, the Department of National Defence said to us, “We can help you with a plane for a couple days, but our capacity is limited. We only have planes available until mid-December, and then we have other operations we’re working on.” So we had a window.

Edlund: That’s when we decided on Dec. 10.

Chomyn: When the email came that said we’re having our first flight on Dec. 10, we all looked at each other and said: “Showtime.”

Cameron: Someone told me, “OK, we have the first flight scheduled, it’s going to be a DND grey tail, and they’re coming on Dec. 10.” I said, “Great, who is going to be on it?” We had thousands of files in processing—people waiting for interviews, finishing interviews, going for health screening, undergoing a variety of security screening—and my team said, “We just have to call and make sure people are ready to leave on that day.”

Michelle Cameron, Canada’s Ambassador to Lebanon, offers a teddy bear to a Syrian child. (Corporal Darcy Lefebvre/Canadian Forces Combat Camera)

King: We got the list of names and we just started calling people. We were working until midnight every day, sometimes 1:00 a.m.

Boudakian: The IOM in Beirut called me and told me my name was on the first flight leaving on Thursday. It was Saturday [Dec. 5], so I had less than a week. I was so surprised—shocked, actually.

Alaji: My family had one side happy, the other side not happy. Do you understand what I mean? When you leave everything you’ve done in your life and you go to another land, you are starting from zero. It is hard.

Ara Shanoian, 26, Syrian refugee: They called us and said me and my brother were on the plane in four days. It was very fast. I didn’t get to say goodbye to all the people I know.

Ghassan Farah, 55, Syrian refugee: We were living with relatives in Lebanon, and they called me at the house one week before and told us we were coming on this airplane. We were so happy to hear we were leaving. All we had been thinking about was leaving the war and coming to a land of peace.

Chitjian: I was outside when I got the phone call, so I called to my husband and told him we will be on a flight to Canada. He thought maybe I am joking with him. I told him: “I am serious, you can believe me.”

Garabedian: The call came on Saturday, five days before leaving. They asked me if I want to go on Thursday or Saturday. I was surprised and I said, “Thursday is so close, so what about Saturday?” They accepted. The next day, Sunday, I was in church and I had another phone call. I went outside, and they said, “Your plane is on Thursday.” There had been a mistake because the flight on Saturday was going to Montreal and the flight on Thursday was going to Toronto. They said, “You’re going on Thursday.” I said, “OK, it is God’s work because I am in church.”

Apkar Mirakian, chair of the refugee sponsorship committee at Toronto’s Armenian Community Centre: We were excited—and panicking. Nearly a hundred people we were sponsoring were coming on that first flight, and we had to arrange everything all of a sudden. The highest amount of arrivals we had until then was 16 in a month.

Ani Tuysusian, refugee sponsorship committee, Toronto’s Armenian Community Centre: We found out a couple of days before that the plane was coming. We didn’t even have the names of everyone on it.

Chomyn: You know what it’s like when you’re working on a big project: it seems like everything goes wrong and you’re into complex problem-solving all day. When we were getting things organized for that first flight, there was one particular day when it seemed like everything needed a little bit of extra effort. We were feeling quite tired, and then out of the blue an email arrived. It was from a lady in Toronto, and she said her husband’s brother and his family had been through the operations centre the day before and were interviewed. She wanted to thank us because this was the first time her brother had been treated like a human being in years. It had a real impact on the team. It really clarified for us what we were working toward. You can’t see the forest for the trees sometimes, and this put everything in perspective.

The Garabedian family. ‘There was a feeling that finally we are away from the war’ (Photo courtesy Vanig Garabedian)

PART III: ‘We are coming!’

Garabedian: They said we had to be at the IOM offices at 6:00 a.m. We went with our luggage—we had a maximum weight of 20 kilos each—and then we took buses to the airport. I was with my wife, Anjilik Jaghlassian, and our three kids: twins Lucie and Sylvie, who were 12, and the younger one, Anna-Maria, who was 10.

Boudakian: I didn’t realize I was going to have all these sad feelings as I was leaving. You can’t really explain what you feel. You want to be stable in your life, to go to the place you think is going to be your country—your home—but you don’t realize that you have to say goodbye to the friends you made and the life you got used to.

Chomyn: By the time I got to the airport, the IOM buses had already arrived and were unloading luggage, and there was a long, long lineup of people waiting to get through the first security check. They were all in good spirits. Some of them were wearing all the clothes they had. They looked like little Michelin men with their winter stuff on.

Mariana Gebeil, Jirair Agigian’s wife: We were with our daughter and our son, 8 and 4. Before we left Lebanon, we had given all our stuff to other people, including my son’s toys. When he saw that, he cried, but he took his favourite small car, a yellow one, and put it in his jacket. Nobody knew until we went through security at the airport and they searched everything. They found his car in his pocket.

Edy Asaad, 20, Syrian refugee: Leaving Lebanon was the worst part. I was wearing [camouflage] pants from Zara. The [airport security] stopped me and asked, “What is this? They look like military pants.” They said I couldn’t move. I had my ticket but because of the pants they were stopping me. It’s kind of racist, but Syrians are always under suspicion. Then one of the Canadian embassy members got involved and solved it.

Cameron: There was one family that really hit me. I actually had to bite my tongue and try to compose myself. It was a couple, the husband spoke English, and their girls were dressed in brand new, bright pink snow jackets. They were clearly ready for winter. I started talking to him and I said, “Are you worried about moving to Canada in the winter?” He looked at me—without a second’s hesitation—and said, “I’d rather snow falling from the sky than bombs.”

Boudakian: In the airport, I saw a friend from my school days, Nerses, who was going on the same plane. We really supported each other, and we were talking about the possibilities and the opportunities that were waiting for us. We were also trying to guess the weather in Canada. It was December, so we were asking each other if we thought we had the proper clothing.

Nerses Sarkisian, 26, Syrian refugee: Ara and Natalie were with me in school. We were shocked to be on the same plane.

Shanoian: Me, Natalie and Nerses were childhood friends from school. It was funny how we were travelling on the same flight. Everyone was talking about what they heard about Canada.

Chitjian: Everybody was excited. “What shall we face in Canada? What is the legal system here? What are Canadian people like?” So many questions.

Sarkisian: There was a Canadian TV journalist. He was taking video and asked me, “Can you say something?” I said, “Hey Canada, we are coming!”

Taryn Fivek, former press officer, IOM: I speak Arabic, so it was decided that I would be able to accompany the refugees on their way to Canada. When I first heard it was going to be a military plane, I pictured a big cargo plane where everyone was going to be strapped down. But it was a pretty normal-looking jet.

The first Syrian refugee family to disembark at Toronto Pearson International Airport. (Kenneth Allan/CBSA/Getty Images)

Warrant Officer Marc Roy, Canadian Forces loadmaster: The plane was a CC-150 Polaris, the Airbus A-310. We have five. 001 is for the Prime Minister, and then we have two passenger airplanes and two refuelling airplanes. We were using a passenger plane.

Capt. Lukas Shaver, Canadian Forces pilot: Usually we take troops out of Canada to somewhere around the world, and then pick up a fresh load of people and take them back to Canada. In this circumstance, there was nothing outgoing. The priority was picking up the passengers in Beirut and transporting them to Canada. We left from Cologne, Germany, early that morning. It’s about a five-hour flight to Beirut, and it was midday when we arrived, around noon or one o’clock. When we landed they were already in the process of screening all the passengers.

Chomyn: The crew was very kind and they gave us a tour so we could see what the plane actually looked like. At one point, we asked them if they had diapers on board. Everyone looked at each other and said, “Diapers?” We pointed out the number of kids who were waiting to get on, and then we put out an emergency call to the IOM to go shopping and bring a load of diapers to the airport. It was the same crew that came back for the second flight, and they thanked us profusely for alerting them about diapers.

Edlund: We knew there were going to be lots of very important people wanting to meet the flight in Toronto, like the Prime Minister, so we’d organized in advance with the IOM to make sure that if people wanted to be photographed, that we had the appropriate consents in place.

Jamkossian: In the airport in Lebanon, some people from the IOM gave me papers and said, “We want to take your pictures in Canada. If you want, sign here.” I signed it, but I didn’t know who I was going to meet.

Garabedian: I signed the waiver, but we didn’t know the Prime Minister would be there.

Chomyn: As we were standing in the boarding area, just before people started getting on board, a young man came up to me. He was quite excited and he said, “Excuse me, excuse me, they tell me I’m going to Prince Edward Island and I don’t know where that is. Is that a good place?” Another Canadian official was standing with me, and we looked at each other and said, “Oh my gosh, you are so lucky. We wish we were going to Prince Edward Island.” We did a real marketing job, and by the time the conversation was over he was convinced the place he was going was the best place on the planet.

Shaver: There were no assigned seats. As soon as we got the green light that people were ready to be loaded, we started at the back and filled seats sequentially until the airplane was full.

Salpy Samuelian, 60, Syrian refugee: My husband has difficulty walking because he has joint problems. He can’t stand too long on his feet. They took care of him and gave him a wheelchair. We were the first ones to enter the military plane.

Shaver: We stood just outside the aircraft door and welcomed them aboard. It was incredible. Everyone was extremely grateful, polite, respectful, and you could tell this was their first step toward Canada. People hugged us, people shook our hands, and every second word was: “Thank you.” It was so rewarding to be able to contribute to this. It was one of the highlights of my career.

Roy: Some of the people were kissing the plane—they would kiss the door. More than one person did that. It was pretty emotional. Others bowed in front of the airplane. There were tears and there were smiles and there was apprehension. There were all kinds of feelings all at once, and you just felt proud. I got choked up a bit.

Garabedian: I will remember this all my life: The last person I saw from the Canadian embassy was in front of the door to the plane. He held me and said, “Go, sir, and make Canada a better place.” I don’t know why he said that, and why to me, but he said it. I looked at his eyes and I said, “I will do that.”

Translator Ahmed Al-Tameemi with Kevork Jamkossian and daughter Madeleine (Adam Scotti/PMO)

PART IV: A perfect landing

Shaver: The takeoff felt different, absolutely. We weren’t carrying 200 military personnel going to do an exercise. These were people who have been displaced from their normal way of life and been through a lot, and we’re giving them a fresh opportunity.

Jamkossian: It was the first time in my life I got on a plane, but I wasn’t scared. I can’t explain to you what I felt, but the previous five days I couldn’t sleep. I waited for that moment.

Sarkisian: My mom was a little bit sad because she still has family in Aleppo. It was hard moving forward but you can’t do anything. Some people made the decision to stay.

Sohair Ashkar, Ghassan Farah’s wife: That was the first time we had been on an airplane. I wasn’t nervous because I was so happy to leave Lebanon.

Asaad: It was a good feeling: a new opportunity at a better life.

Shant Gergian, 20, Syrian refugee: I can’t remember everything in detail because it was like a dream.

Shanoian: I sat in the middle, between Nerses and Natalie.

Sarkisian: You don’t have a seat number like a normal flight. We told one of the military guys that we’re all friends and wanted to sit beside each other and they said that’s cool. We were at the back because we were one of the first people on the plane.

Boudakian: I won’t forget that day. It was a transitional day of my life, and what I remember most is how nice the people were, especially the soldiers. You already felt a connection to this country even on the plane.

Farah: I can’t forget it, how nice they were.

Agigian: I remember the service in the airplane was very good. We were happy because the army people, they helped us. They brought us food. It was very different for us.

Shanoian: We didn’t feel like they were actual soldiers. We never saw soldiers like this: just doing their job and talking nicely with us. When you see soldiers in our country, they’re different, more aggressive.

Ashkar: The crew was so nice. They served us meals, more than enough. They were offering us everything: cake, juice, cheese. “If you like this one, it’s OK. If you don’t, there is another choice.”

Gergian: The food was good. It was chicken and rice. It was a new kind of taste. I don’t know what kind of flavour was in it. It was not as spicy.

Chitjian: For the first time, we felt ourselves as human beings.

Fivek: I remember walking the aisles of the plane, pretty much constantly, trying to see if anybody needed anything and if everyone was feeling all right. At one point there were a couple of people who had pretty major headaches, so we had to break into the First Aid kit and get some paracetamol.

Garabedian: I was joking with one of the soldiers. I asked if they have a drink [alcohol]. He said, “This is a military plane, you can’t have a drink here.” I said, “Of course this is a military plane and you are from the army, but we are ordinary people, we are civilians, and we need a drink.” He said again, “No sir, we don’t have that.” I said, “Maybe you hide it somewhere.”

Shaver: It’s about a five-hour flight from Beirut back to Cologne, so including the layover to get everyone on board, it was about a 15-hour day for us. But it was nothing compared to what these people had gone through, and I think the crew would have worked another 10 or 12 hours if it meant getting the mission accomplished.

Roy: There was a crew change in Cologne and the plane was refuelled before it continued on to Toronto.

Gergian: We landed in Germany and we stayed in the plane for an hour.

Jamkossian: I was sitting in a window seat beside my wife and my daughter, Madeleine. She was one year and three months old. She was so good. She was sleeping all the time.

Capt. Lukas Shaver and Warrant Officer Marc Roy (Corporal Darcy Lefebvre/Canadian Forces Combat Camera)

Jurisic: Something I was consumed with that day—I’ll never forget—was the degree of interest there was from VIPs and from the media. There was a lot of stick-handling around that. We had the Prime Minister coming to Pearson that day, we had the ministers of the [Syrian refugee cabinet] committee—Minister John McCallum, Minister Jane Philpott, Minister Harjit Sajjan—and we had [Toronto] Mayor John Tory and [Mississauga] Mayor Bonnie Crombie. There is a lot of coordination that goes around VIPs of that stature, but our single focus was making this as smooth as possible for the refugees themselves. It’s a fine balance.

Maria Petrolo, terminal service representative, Pearson: I’ve been in the airport 26 years. I basically live in the airport, and I love it. I came in a couple of hours early just to prep and make sure everything was in order as it should be. To me, it was no longer a terminal. It was a home where these people were being welcomed to Canada.

Jurisic: We were really happy with the way everything came together. The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) needed to process arrivals, so they had their equipment set up to do biometrics and take fingerprints. We also had Service Canada there, ready to issue Social Insurance Numbers on the spot. And we had this huge area—the Duty Free Shop of the terminal, when it was operational—that we used as the clothing area. We were shoving mitts and hats into the shelves where they used to sell alcohol and tobacco.

Suchita Jain, manager for quarantine services, Public Health Agency: We had a station set up that if somebody was ill, they’d come to us for assessment. The Ontario Emergency Medical Assistance Team had a room with four beds, nurses, nurse practitioners and physicians to help.

Franzgrote: There was a play centre set up for the kids with a train set, a dollhouse, child-sized couches, a play kitchen. There were Arabic signs. That was a big thing; we wanted to make sure people understood where the washrooms were, where the water fountains were, that the water was potable.

Jain: Everybody was moving around. I stood back and remember thinking, “Oh my God, this is like a chaotic Indian wedding where everybody has a small part but everybody is so excited for the main event.”

Ahmed Al-Tameemi, Arabic interpreter: I am originally from Iraq. I came to Canada six years ago and I have a master’s degree in linguistics. I am a freelance interpreter, and I was chosen to be a supervising interpreter for the team working at the Welcome Centre. I arrived at the airport at 6 p.m. because the flight was scheduled to arrive around 9 p.m. It was a feeling that words can’t describe very well. I arrived at Pearson when I came to Canada, and when I drove to the airport that day it all came back to me—the first day I arrived in Canada. I was proud to be going to meet these people arriving in Canada and giving them a warm welcome.

Arif Virani, parliamentary secretary to the IRCC minister: I was driven out to the infield terminal by some CBSA officers. I asked them quite candidly, “Is what’s being asked of you tough?” The response I got took me aback a bit. I got looked at through the rearview mirror by a very stern CBSA person and he said to me, quite categorically, “We are doing our duty. We are committed to this project that the country is undertaking. This is where we want to be.”

Jurisic: We gave the Prime Minister a tour of the facility. I was walking him around—“This is what we’re doing here, and this is what we’re doing there”—and he got to meet some people. And then he asked for all the staff, all 150-plus people, to gather in this one open area of the terminal. He wanted to speak and to thank everyone.

Franzgrote: I remember the plane was late, and it seemed like a neverending waiting game. It felt so much longer because of the great anticipation.

Bonnie Crombie, Mississauga mayor: Everyone was very anxious because there was a long delay, so we were all kept in a holding room. We were pacing a little bit and drinking coffee.

John Tory, Toronto mayor: We ended up having a couple of hours when we were told we would have a few minutes. So I ended up having conversations with a number of people there about different issues. I actually had a very long chat with Jenny Kwan, the NDP MP from Vancouver, about supervised injection sites, because she’d been through all that.

Virani: I’m a Muslim so I have some fluency in Arabic. My Arabic is not flawless but we were going through some basic greetings, helping some people with their pronunciation. I remember [Ontario] Premier [Kathleen] Wynne was pretty flawless in her pronouncing how to say ahlan wasahlan, which means “welcome.”

Boudakian: We were so excited when we finally got closer to Canadian land.

Chitjian: It was after 11 p.m. so everything was dark, but it was beautiful, the lights.

Jamkossian: I could see squares of lights and it was perfect. I don’t forget this moment, I liked it too much.

Sarkisian: You would see lights for infinity.

Farah: The pilot landed at the airport so smoothly that we couldn’t believe it.

Chitjian: Everybody cheered because the pilot was so perfect. We never felt like we were landing.

Garabedian: People were applauding when the plane landed. There was a feeling that finally we are away from the war. Finally we are safe. Finally we are going to take the first step toward our future home.

Jirair Agigian’s daughter, Aster, walked to school to the sound of bombs. (Adam Scotti/PMO)

PART V: ‘Thank you, Canada’

Alex Macleod, commissionaire: Our role was to provide security for the infield terminal. I was on the lower level, right near a window where we could see the nose of the plane coming toward the building. It was an exciting moment: “Well, here we go.”

Jurisic: There was a quiet reverence. We weren’t all going, “Woo hoo, they’re here!” It was almost like a collective holding of our breath.

Charles Bernard, maintenance response manager, Pearson: I watched the airplane door open and saw the passengers come off. It was absolutely amazing. I was standing with my associate director and my electrician inside the bridge. It put tears in my eyes, really, just to watch them come out. I watched a person actually bow down and kiss the ground. I thought, “Thank God I am Canadian.”

Jurisic: All the processing with the Canada Border Services Agency was done in private. We weren’t allowed in that area. We were just on the other side.

Mary Jago, communications adviser, IRCC: I brought the cameras upstairs, we got set up, and then we waited. It took a bit longer than I had anticipated, just because it was something that was very real. When I work with a press pool, I like to tell the journalists, “There are five people coming through, here are their names, here are their ages.” But it was a bit of a running play. We didn’t know which family was going to come out first.

Al-Tameemi: I was wearing a yellow vest that showed I was an interpreter. I introduced myself to one of the press coordinators and informed her that I’m here, ready to interpret for the Prime Minister when he meets the families. She said, “Oh, excellent.”

Jago: The Prime Minister and the premier were in place, and the media was in place, and then, as I was waiting in the hallway, the Prime Minister actually walked over to where I was standing and was looking down the hallway with me. He made a comment about the time—I don’t remember exactly what time it was—and I responded that I had completely checked out of time. Then this family, this wonderful family, I saw them coming.

Al-Tameemi: There was a husband and wife, and the husband was carrying his little girl in his arm.

Jago: I walked up to them and I said, “Welcome to Canada. Would you like to come and meet our Prime Minister?”

Jamkossian: If you see the video, you can see my face. I was very, very surprised to see the Prime Minister there. I knew him.

Al-Tameemi: You have this feeling of, “Is this real?” But I had a duty to complete, so I focused all my attention on the communication. The family knew some English, like “thank you,” and in the beginning the father tried to speak some English. Then he realized he can’t, so he started to speak in Arabic.

Jamkossian: I didn’t speak English when I come, but I understood a little bit. He said, “Welcome to your new home.” If the Prime Minister says to me, “Welcome to your new home,” I think I can live here and be happy.

Jago: We were in very tight quarters with the photographers, and the family had a little girl about a year old. The photographers were very close to her shooting, and I kept saying, “Guys, step back.” They would step back, but it was such a great shot that they would step forward again. I thought, “OK, if she starts to cry or appears distressed, I’ll be able to convince everyone to give a little space.” She never, ever appeared distressed, and I was amazed by that. I remember thinking, “There is something happening in this moment.” It wasn’t until later that I saw the power of that moment and how it was broadcast to the world.

Jamkossian: After, if I go to the market or wherever I go, people come and say to me, “I see her in the TV. She is the first refugee coming to Canada.”

Garabedian: When I shook hands with Mr. Trudeau, I felt how amazing the country is—not only him, the country. I didn’t need the translator. I spoke English. The first thing he said was, “Welcome home.” We felt at that moment that we actually are at home.

Gebeil: The Prime Minister said hello and hugged my husband and hugged my kids. He said, “Welcome to Canada.” He gave us all coats, and we use them every day. My jacket and my husband’s jacket are black. My daughter’s is blue and my son’s is blue.

Boudakian: The jacket they gave me is purple and purple is my favourite colour.

Crombie: Mayor Tory and I were together, handing out mittens and hats. It was such an emotional and inspirational experience, one I’ll always treasure.

Virani: I came to Canada as a refugee from Uganda in 1972. I was 10½ months old so I don’t have a recollection of arriving in Dorval airport in Montreal. But I started to picture what my family would have been composed of: 10-month-old me, four-year-old sister, and two parents in their early thirties. I started to find families that looked like that and that’s when it really came to bear: that’s me four decades ago.

Franzgrote: We see trying situations every day. If you walk through the arrivals hall any time of the day, it’s usually a tear-jerking experience. But this was definitely a different feeling. We rarely get the opportunity to affect change in this way, to make a difference, to leave a stamp. That’s how this day differs.

Al-Tameemi: It felt like something nice that you never want to end. Watching the children play in the play area, they just felt at home completely. You can feel that. Their parents were looking at them, and you could see some of them in tears. Their kids were happy and safe. Some of the parents asked me, “Will it be long before my kids go to school?” I told them, “In no time—and they will be your interpreters in the future.”

Jurisic: I will never forget this. There was a gentleman who came off that first flight, and he had with him a handwritten note. The gentleman was so intent on finding a government official to present this message to. Our security detail was the Corps of Commissionaires and they have an official-looking uniform, so this man made his way toward Alex.

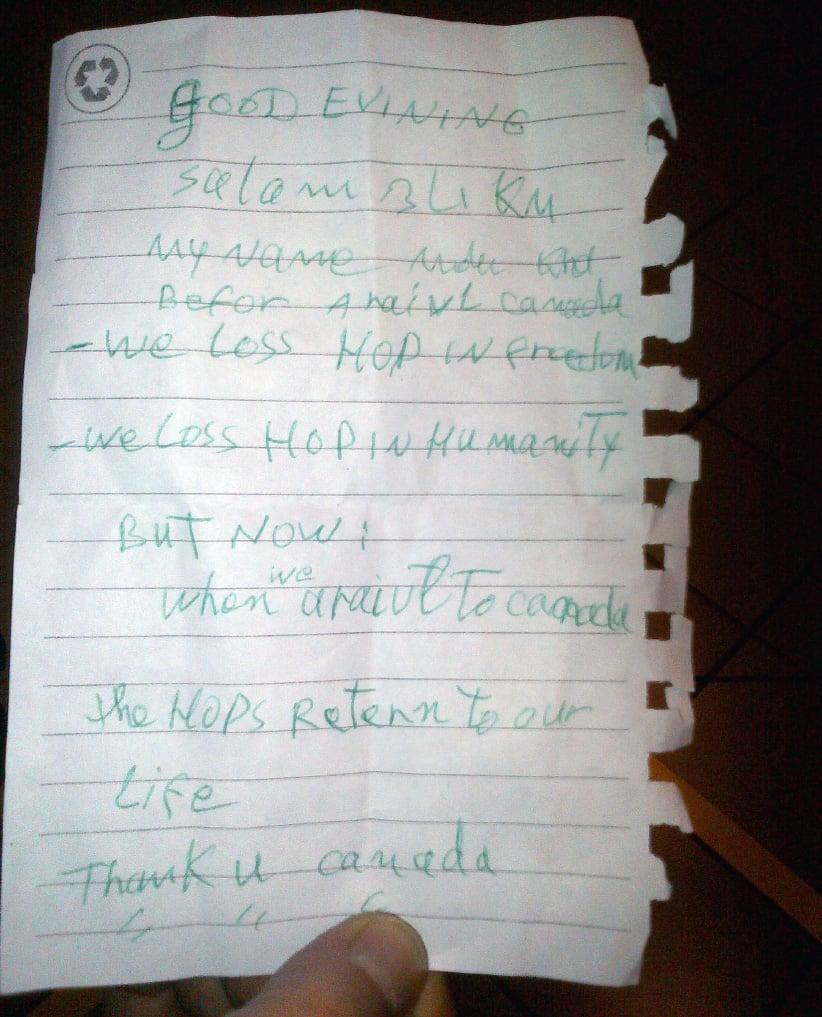

A refugee letter given to a commissionaire (Photo courtesy Alex Macleod)

Macleod: He wasn’t speaking English so I couldn’t understand what he was saying, but he was smiling and positive. I shook his hand and then he handed me this letter. It took me a minute or two to decipher what he was saying. I was quite moved by it.

Jurisic: I have a picture of this letter. It says, “Salaam Alaikum … Before we arrived in Canada, we lose hope in freedom, we lose hope in humanity. But now when we arrive to Canada the hope returns to our life. Thank you Canada.” When Alex came to find me to show me this note, he was in tears.

Macleod: It was so far from my reality that it was really hard for me to absorb. It sort of stopped me in my tracks, and I didn’t stop thinking about it for a very long time. To hear that he had given up hope, the situation stopped being something that was distant—a war in another country—and became something that was right here in my face.

Al-Tameemi: I left the airport at 5:30 a.m. I was there for 11½ hours. I was thinking as I drove, “Canada made history today, and I was part of that history.” When I arrived home, I was just waiting for my daughters to wake up so they could see me on the TV interpreting for the Prime Minister and welcoming people who were are now safe in Canada.

Grundison: We thought we had moved a mountain to get through that first flight. It had taken us weeks to get to that point, so we thought, “We are at that historic moment.” But it had just started. It really was the end of the beginning.

Reporters: Michael Friscolanti, Aaron Hutchins

Editor: Colin Campbell

Art director: Stephen Gregory

Director of Photography: Liz Sullivan

Assistant editor, digital: Nick Taylor-Vaisey

Published: November 29, 2016