‘If I had known what it meant for a woman to invade a man’s world I wouldn’t have been able to face it’

Agnes Macphail, the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons, on sexism in politics and daily life

Share

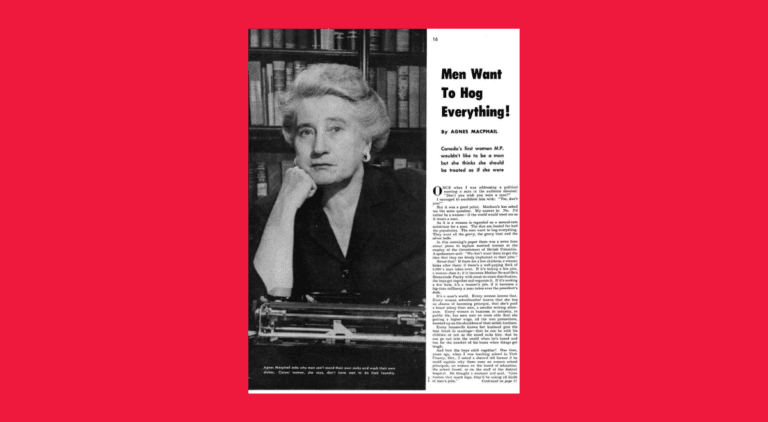

Reflecting on her career, Agnes Macphail wrote in the Sept. 15, 1949 issue of Maclean’s. Macphail became the first woman elected to the House of Commons 100 years ago, on Dec. 6, 1921.

ONCE when I was addressing a political meeting a man in the audience shouted: “Don’t you wish you were a man?”

I managed to annihilate him with: “Yes, don’t you?”

But it was a good point. Maclean’s has asked me the same question. My answer is: No. I’d rather be a woman—if the world would treat me as it treats a man.

As it is a woman is regarded as a second-rate substitute for a man. The dice are loaded for half the population. The men want to hog everything. They want all the gravy, the gravy boat and the silver ladle.

In this morning’s paper there was a news item about plans to replace married women in the employ of the Government of British Columbia. A spokesman said: “We don’t want them to get the idea that they are firmly implanted in their jobs.”

Never that! If there are a few chickens, a woman looks after them; if there’s a well-paying flock of 5,000 a man takes over. If it’s baking a few pies, a woman does it; if it becomes Mother So-and-So’s Homemade Pastry with coast-to-coast distribution, the boys get together and organize it. If it’s making a few hats, it’s a woman’s job; if it becomes a big-time millinery a man takes over the president’s desk.

It’s a man’s world. Every woman knows that. Every woman schoolteacher knows that she has no chance of becoming principal, that she’s paid a lower salary than men, a smaller retiring allowance. Every woman in business, in industry, in public life, has seen men no more able than she getting a higher wage, all the nice promotions, boosted up on the shoulders of their selfish brothers.

Every housewife knows her husband gets the best break in marriage—that he can be with his children or not as the mood suits him; that he can go out into the world when he’s bored and run for the comfort of his home when things get tough.

And how the boys stick together! One time, years ago, when I was teaching school in York County, Ont., I asked a shrewd old farmer if he could explain why there were no women school principals, no women on the board of education, the school board, or on the staff of the district hospital. He thought a moment and said, “Give women that much rope, they’d be taking all kinds of men’s jobs.”

The logic was perfect; but the premise was wrong. To him it was as natural as the seasons that the juicy plums belong to the men. It reminded me of the visitor to Westminster Abbey who was discovered kneeling in the centre of the floor. Asked what he was doing there he explained he was praying. He was told, “But if we allowed everybody to do that we’d have people praying all over the place.”

Men still regard a capable woman as a departure from the normal. As I write there is an account in the newspapers about a woman who appealed for permission to fly over Canada. She was told, “Go home and take care of your baby.”

What kind of a remark is that? Her ability or inability to handle a plane wasn’t questioned: it wasn’t even mentioned. She was treated rudely only as a woman. What had having a baby to do with her right to fly over Canada in a plane? Why not tell Prime Minister St. Laurent to go home and mind his grandchildren?

Every woman driver has gone through similar experiences. I did myself just recently. I was crawling along Toronto’s Bloor Street looking for a place to park when a car full of teen-age youngsters nearly ran into me. As they passed I heard one lad say, “What could you expect? It’s only a woman.”

Those youngsters were already cheering for the winning team. And it isn’t only the youngsters. A few days previously a traffic policeman had abused me for at least a half a minute for making a wide turn, obviously feeling a bit pompous because he was dealing with a woman. It was the longest lecture any man has ever given me without having his ego punctured. I didn’t say a word. I decided that there wouldn’t be enough time to say what I had to say between green lights.

Yet women have proved themselves just as capable as men in cars, as in most other fields. In spite of the fact that they have to beg, cajole and flatter their husbands into letting them learn to drive, they turn out to be better motorists than their husbands; not better drivers, perhaps, but better motorists—more careful of human life, more considerate of the rights of others. Any instructor of any driving school will tell you that. In Ontario for 1948, although 17.3% of licensed drivers were women, the percentage of accidents involving women drivers was only 4.8.

There are modifying factors, of course; men do more driving than women as a rule. Still, at least until a closer comparison is made, it seems neither fair nor reasonable to assume that women are more of a menace behind the wheel than men.

Women are just as well suited as men to manage the world’s affairs; far better suited to serve the people because looking after others is part of their nature. Women are naturally unselfish; unselfish with men, unselfish with children. Women don’t like wars—they don’t want to raise their sons to be shot to satisfy the ego of some windbag.

Men on the other hand act like selfish children. They are spoiled from the time they are born, first by their mothers, then by their wives and daughters. If a man loses a collar button he simply needs to make a noise and his wife or his daughters find it for him. My own father was a dear fellow, but I don’t think he ever in his life found his shirt and his studs at the same time. He could usually find his shirt and sometimes he could find his studs, but never did he find both his shirt and his studs.

Men couldn’t do their work without women. Some men will even admit it. When Prime Minister Mackenzie King made it known that he didn’t want any of his cabinet ministers to have women secretaries, W. R. Motherwell, Minister of Agriculture in King’s cabinet, faced with the possibility of having to do without Miss Cummings, his secretary, said: “To — with him. I couldn’t get along without her.”

Often a woman does the work while the man provides the front. And what a front! A few weeks ago a woman friend of mine went on a three-day buying trip for a small women’s wear shop. She called on a well-known blouse manufacturer in Montreal, but found that he was at an important luncheon and would be away most of the afternoon. His secretary, a quiet little woman in her 30’s, took charge of my friend, showed her samples and quoted her prices.

The second day the manufacturer came out of his office, boomed a hearty welcome and turned my friend over to his secretary again. His secretary once more took charge of things neatly and efficiently.

When on the last day my friend went back to wind up her business she didn’t bother to ask for the owner; she was doing fine with the secretary.

That night she went to a convention and listened to the blouse manufacturer give an impressive talk on how he ran his business like a baseball team. She heard one man whisper ecstatically, “There’s a grand old man.”

The world is full of “grand old men” who could go on a two-year cruise without being missed as long as their secretaries are on the job to look after things. Why are there no “grand old women”?

Is War Just “a Binge”?

And, by the way, why is a fumbling male human known as an “old woman”? He isn’t an old woman, or anything like an old woman. If he were an old woman he’d have some sense. What be is is a fuddle-headed old man. Why not say so?

If I had known before I entered public life what it meant for a woman to invade a man’s world I wouldn’t have been able to face it, just, as most men wouldn’t be able to face war if they knew what it meant, instead of thinking of it as a prolonged binge away from their wives.

On the night in 1921 when I was nominated as U.F.O. candidate for Southeast Grey I learned that after I’d left the hall an old farmer, hearing that a woman would represent his party, snapped, “What? Are there no men left in Southeast Grey!”

I was well-informed on that particular election issue: well enough informed that the farmers had been in the habit of dropping in at the school where I was teaching to ask my opinions. Yet it took strenuous campaigning for two months just to stop people saying, “We can’t have a woman.”

I won that election in spite of being a woman.

In the first parliament I was in, J. S. Woodsworth, at that time the member from Winnipeg, picked a few of his favorites to be his guests at a luncheon in the parliamentary restaurant. When he told J. B. Bourassa, the Liberal from Levis, Que., who would be there, Bourassa said, “If Agnes Macphail is going, I’m not.”

Years later Bourassa told me, “You are an awful plague to me. I’ll be frank: I still don’t think a woman has any place in politics, but I must admit you’ve done all the right things. Now my daughters are always throwing you at me.”

Not that men’s disapproval of women usually takes so personal a turn. I was only 31 when I was first elected and I never lacked men to take me to dinner. I even had a few narrow escapes from marriage. I always got away before we reached the altar.

I never did like cooking, housework, or finding men’s collar buttons. I don’t think I would have made the kind of meekly helpful wife men like. One time it came back to me that a man to whom I’d been introduced said, “I wouldn’t want to be married to that woman. She could see right through me.”

Salute—on Both Cheeks

I was treated with courtesy. I was even paid a few compliments, including one from Prime Minister R. B. Bennett, of whom I was very fond. He once told me, “Agnes, you have a lovely ankle.”

Whenever R. B. Bennett came down to chat with me in the Commons the man who happened to be sitting beside me always made a point of giving way to him. One time it was G. G. Coote, the member from Macleod, Alta., and when R. B. had left, Coote said indignantly, “What’s the matter with him? Does he think we’re all blind?”

One of the most consistently gallant was Jean-Francois Pouliot, the Liberal from Temiscouata, Que. He was completely charming, almost too charming on one occasion. It was a time when Hugh Cleaver, M.P. for Halton, Ont., John Diefenbaker, of Lake Centre, Sask., Pouliot and myself had been invited to give a talk to students on parliamentary affairs in Toronto University’s Convocation Hall.

When Pouliot, who was the last to arrive, saw me he sighed, “Ah, Agnes,” rushed over and saluted me on both cheeks.

The other men in the room looked as if they thought they shouldn’t have been there. They probably thought a bit uneasily of a smear campaign that had been launched against me early in my career which pictured me as a sort of feminine roué.

But I was under no illusions about most of the superficial courtesies extended me. The old ideas of chivalry justify men in thinking of women as a rather poor choice in human beings. Put her on a pedestal, then put pedestal and all in a cage.

I had to tell several well-meaning boys that I wasn’t a quivering helplessness who had to be loaded onto streetcars, buses and trains like a sack of oatmeal.

When I first came to the House of Commons and walked out into the lobby men sprang to their feet. I asked them to sit down since I’d come to walk around. I didn’t want them doing me favors. I figured I was going to have trouble enough.

I was right. I found that I couldn’t quietly do my job without being ballyhooed like the bearded lady. People in the gallery pointed me out and said, “Right there. That’s her!”

I lost 12 pounds while I was in the Commons. (I wish I could do it again.)

I couldn’t open my mouth to say the simplest thing without it appearing in the papers. I was a curiosity, a freak. And you know the way the world treats freaks.

Poor G. G. Coote, who was my deskmate in the Commons for 10 years, got as tired of it as I did. So many eyes were on our section of the House that he began to feel like a freak himself. One day we were strolling through the hook department of a Toronto department store when we saw a book called, “Man in a Cage.” He called a clerk, pointed to the book, and said, “That’s me. I’ll buy it.”

When I first found myself in politics I rubbed my hands and said to myself, “Now to get down to brass tacks. Now to get things done.” I’d forgotten for a moment that I was a woman. Men don’t like women telling them how to get things done.

A woman in a man’s world has to cope at every turn with the danger of wounding the male ego. All men are too pompous. Their egos are a bother. They’re like the big balloons that were used over London during the war.

Soon after I was elected for the first time I gave a talk to a woman’s audience into which one solitary man had found his way. That one man spoiled my talk and almost spoiled my evening. I found myself editing everything I had to say so that I wouldn’t hurt the poor boy’s feelings. It was the first time I’d come up against that particular kind of handicap. It wasn’t the last time.

An audience of all women is fine; you can get down to cases. An audience all of men, or half of men and half women, is all right. When men are backed up by one another their morale is at its usual high. But one man is a problem. You can’t call a spade a spade. You must be constantly reminding yourself that a bundle of sensitivity and puffed ego is present. It’s a terrible bore to women who are trying to get things done.

There were many things that made me realize that this is a man’s world, but I managed to survive. I survived partly because I have a temper like a tinderbox soaked in coal oil and a tongue that men have learned to respect.

I threw sparks early. I think the first time was when Mitchell Hepburn made the remark that there would never be any difficulty in having women to do the work for men as long as there were wedding rings.

But, more important, I managed to keep a sense of humor for which 1 was many times grateful. Without it I’m afraid I never could have lasted.

But, most important, I tried to be natural, to say what I thought sincerely, to abide by my own standards. That sums up the most important advice I can pass on to women today.

Women have made encouraging progress in the past 20 years, but we still need more women doing more things. We need more women in welfare work, on school boards, on hospital boards and in government. Our House of Commons is now all-male again; I didn’t think it would ever go back after my 14 years there.

My advice to women is: Don’t let men make clothes horses out of you to demonstrate their economic prowess. Don’t let them make you props for their advertisements. As I write this I can see on my shelf a package of soapless detergent which shows a smiling model washing the dishes. Don’t let the men fool you. There is nothing modern, progressive, advanced or desirable about having to slave over dishes, either with or without soapless detergents.

Don’t be among the women who are afraid of their men losing their jobs to able women. Don’t let men convince you that women are a naturally destined subjugated race, a race of slaves who do the washing, ironing and housework. Why can’t men be responsible for their own socks and shirts? Career women don’t have men doing their laundry for them.

If there is one thing that makes me boil it’s the sight of grown men, men in public office, swelling before the camera while their wives hover helpfully in the background. What are these men that they can’t take care of themselves? Babes in arms?

Above all be yourself. Don’t imitate anybody. One of the most deplorable sights in the world today is that of women trying to act like men. Women wrestlers! They make you blush for the human race. If these women must try to imitate men, why pick the “he”-man as their pattern? The “he”-man—the aggressive male—is the one who causes the trouble, the suffering, the wars, the one who obstructs social reform. He’s a muscle-bound hang-over from the days when a man’s importance to the group depended on how much he could lift. But we have cranes to do the lifting now: and bulging muscles are too often synonymous with flat heads.

Today’s “he”-man doesn’t always wear a sombrero, wrestler’s tights or a soldier’s uniform. In his most troublesome form he wears a shiny top hat or grey business suit. The get-rich-quick boys, the politicians, the boys on the make. And they’re busy as bees.

I could be in the Federal Cabinet if I’d been on the make for Agnes Macphail. I was offered everything in the book. I was told if I’d take a certain line I could choose what I liked except the prime ministership or the ministership of finance.

But all men don’t like wrestling matches, bull fights and wars. There are civilized men, men with a sense of responsibility, with wisdom and tolerance.

There are even some men who think a woman should get a fair break. Not many, but enough to make the struggle seem worth while.