Culture

A Voyage to the North

A new exhibit chronicles daily Indigenous life in northern Ontario in the ’50s and ’60s

TikTok’s Reigning Math Queen

One and a half million math converts have flocked to Santos’s @onlinekyne account for camp explanations of quadratic equations and square roots

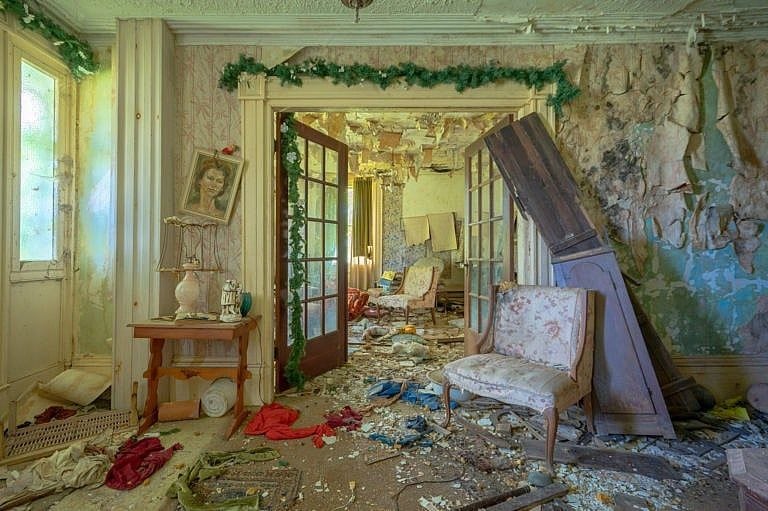

The Ontario photographer who shoots abandoned churches, schools and mansions

His images reveal the things we leave behind

Montreal’s Gabriel Diallo is a tennis giant in the making

At 22 (and six-foot-eight), Diallo is a towering presence at the net, drawing comparisons to another Canadian upstart: Milos Raonic

How Calgary’s Kablusiak made Inuit art pop

The Inuvialuk artist’s oeuvre—complete with Furbies, soapstone tampons and satirical selfie backgrounds—has garnered plenty of attention, a bit of outrage and even a Sobey Art Award

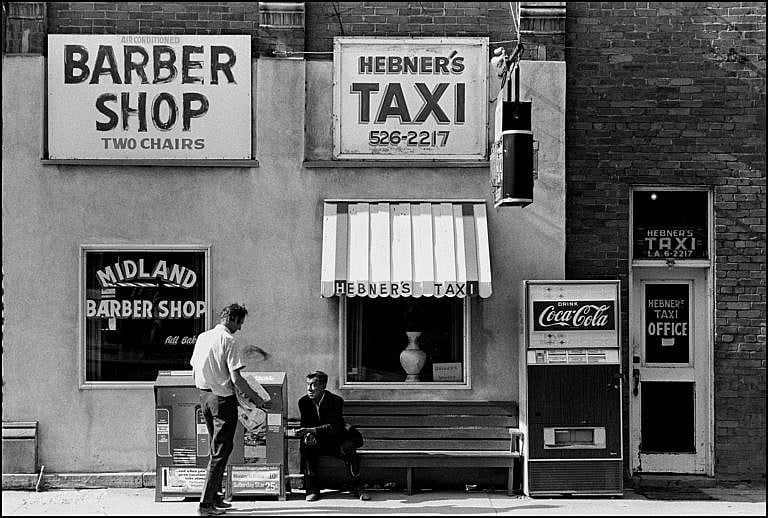

This new exhibit showcases six decades of quirky Canadian street photography

Canadian photojournalist Ian MacEachern shoots iconic street scenes and eccentric characters

Meet Yannick Nézet-Séguin, the maestro behind Bradley Cooper’s Maestro

Nézet-Séguin’s savant-like conducting chops made him a star in the classical music world. Then Hollywood came calling.

This librarian turned photographer takes stark, dazzling images of the Prairies

Sandra Herber braves treacherous winter weather to shoot the region’s iconic grain elevators and churches

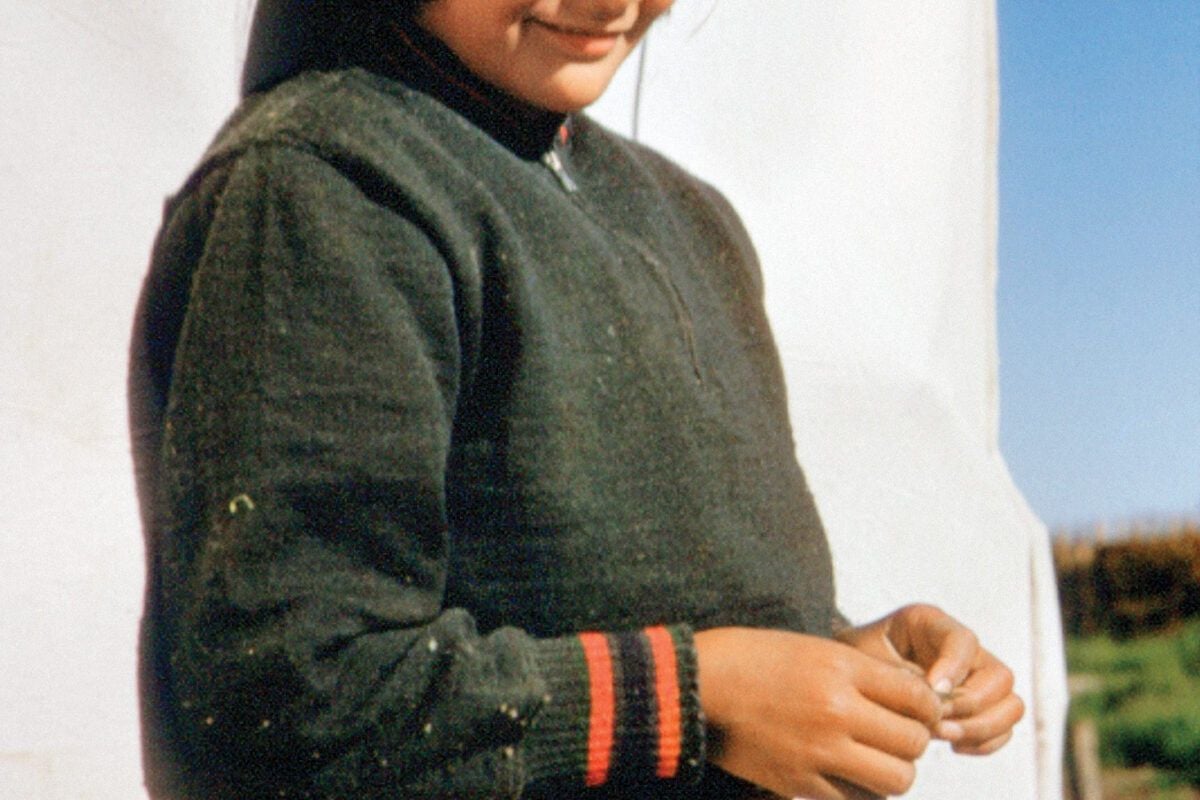

For knitwear designer Paolina Russo, it’s always sweater weather

Paolina Russo’s designs have found favour among cool-girl celebs like Phoebe Bridgers and buyers at Nordstrom. Not bad for a former fashion blogger from Markham, Ontario.

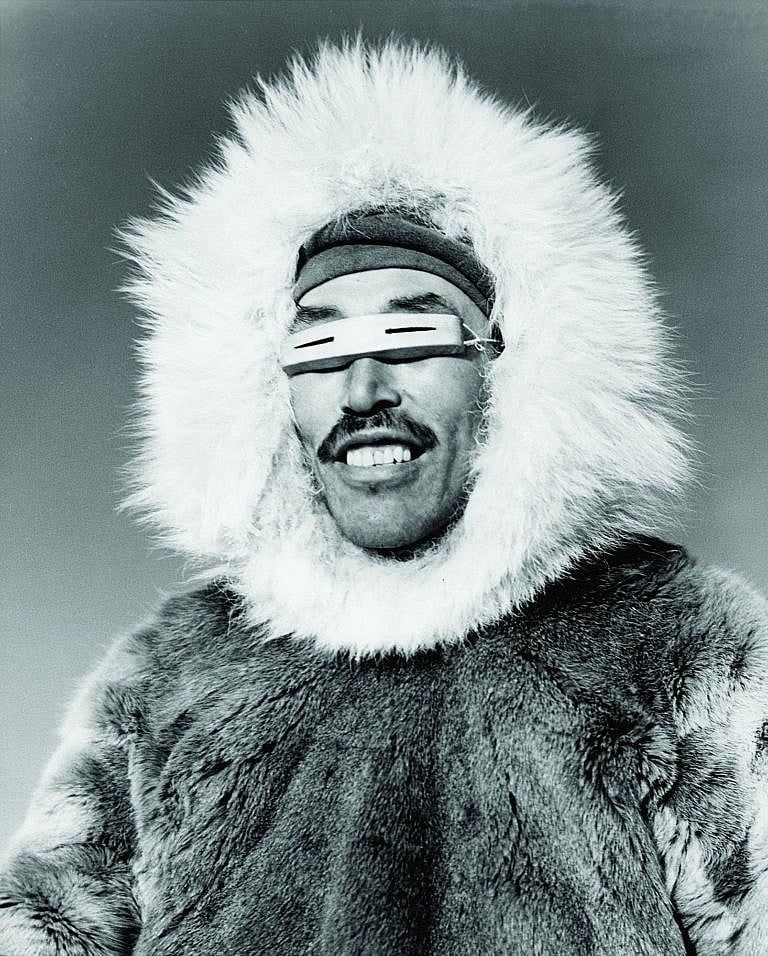

This mid-century photographer captured the Inuit’s disappearing way of life

A new book chronicles the Canadian Arctic expeditions of photographer Richard Harrington, who visited the Canadian Arctic six times between 1948 and 1953

The Building: A cozy, communal gallery for Fredericton’s art lovers

Don’t let the imposing columns outside Fredericton’s Beaverbrook Art Gallery fool you—its new expansion is a warm, inviting space for art buffs (and an ideal party spot)