Ahead by a year: Remembering the Hip’s last show

‘It was a communal experience of religious proportions.’ Canada’s musical luminaries remember the Tragically Hip’s final show.

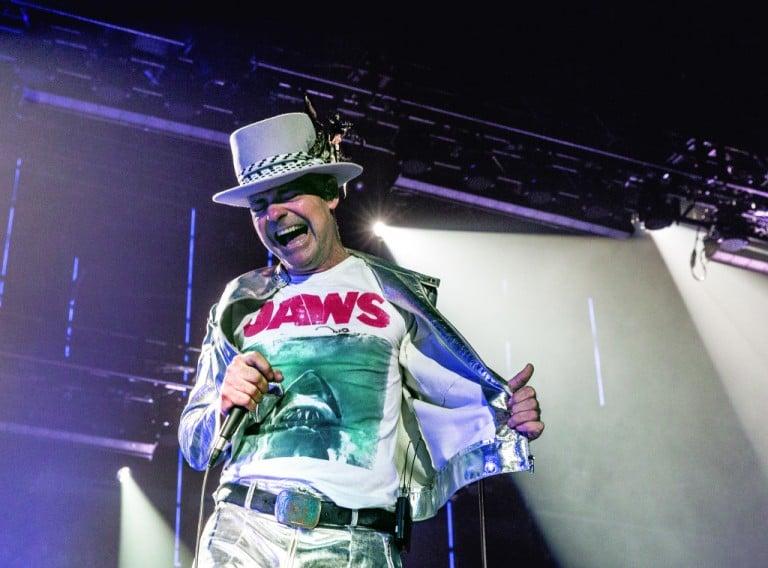

Gord Downie, lead singer for the Tragically Hip, performs during the band’s last concert in Kingston. (David Bastedo/The Tragically Hip)

Share

This time last year, the Tragically Hip were entering the final stretch of their 2016 tour, an event coloured by singer Gord Downie’s diagnosis of terminal brain cancer. It all culminated with their final show on Aug. 20, 2016, in the band’s hometown of Kingston in front of 6,700 people in the K-Rock Centre and 25,000 in Springer Market Square around the corner; at least 11.7 million Canadians watched the CBC broadcast of the concert. Over the band’s 32-year career, the Hip became mentors to generations of Canadian musicians. In an exclusive excerpt from my upcoming biography of the band, The Never-Ending Present—due in early 2018—22 of the Hip’s peers reminisce about where they were and what they were thinking on that unforgettable night.

Allan Gregg: principal, Earnscliffe Strategy Group

Relationship with the band: Co-manager, 1986-94

I watched it on television. My kids literally grew up on Gord’s lap, at band meetings in my basement. I brought them to the Air Canada Centre show [in Toronto]. We didn’t go backstage. The show was remarkable. I should’ve felt deadeningly sad, but I didn’t—because Gord didn’t. He looked like he was having the time of his life. I told my kids that they’ll be singing “Bobcaygeon” 50 years from now. That will be Gord’s legacy: the songs. Those songs will be here forever and part of the Canadian fabric when you’re an old, old man.

Colin Cripps: guitarist, Blue Rodeo

Relationship: guitarist in Crash Vegas, which opened for the Tragically Hip from 1991 to 1993

I was playing at the Molson Amphitheatre [in Toronto] with Blue Rodeo that night. We played “Bobcaygeon” as a tribute. Somehow [the tech crew] got a feed to show [the Hip] playing live on our screens, and they were also doing “Bobcaygeon.” Total f–king fluke. We had no idea that was happening. Suddenly people started going crazy, and we looked up and there’s Gord. It was an amazing Canadian moment. People were crying. We were emotional. It was fantastic. You couldn’t help but feel all the history you have together.

I watched about a third of [the Kingston show] later. I couldn’t watch the whole thing, to be honest. I went to two of the shows, one in Toronto and one in Hamilton. I stood at [guitar tech] Billy Ray’s station at the side of the stage. It was an amazing show, both times. I was blown away. That was enough for me. The last show was too much. They’re my buddies and I’m a big fan. If I was watching it in the moment, it would be different. But to go back and watch it? No. It was a communal experience of religious proportions. People were celebrating the Hip but also all of us being a part of that community, and feeling that through music, which is such a powerful thing.

Michelle McAdorey: singer

Relationship: Singer in Crash Vegas, which opened for the Tragically Hip from 1991 to 1993

I was at the Blue Rodeo show. That was really intense, for so many reasons, for me, personally. Backstage at this Blue Rodeo gig everyone was watching the Tragically Hip show. Then Blue Rodeo did their Tragically Hip tribute [by playing “Bobcaygeon”], and I had a friend there who was so riddled with cancer—and that was the last time I saw him. There were so many emotions. I’d watch a bit of the Hip show, then a bit of the Blue Rodeo show, then I’d be talking to my friend. That was an overwhelming day and night. It was such a gorgeous moment, that “Bobcaygeon” moment. But it was hard to watch.

Chris Tsangarides: producer

Relationship: produced Fully Completely (1992)

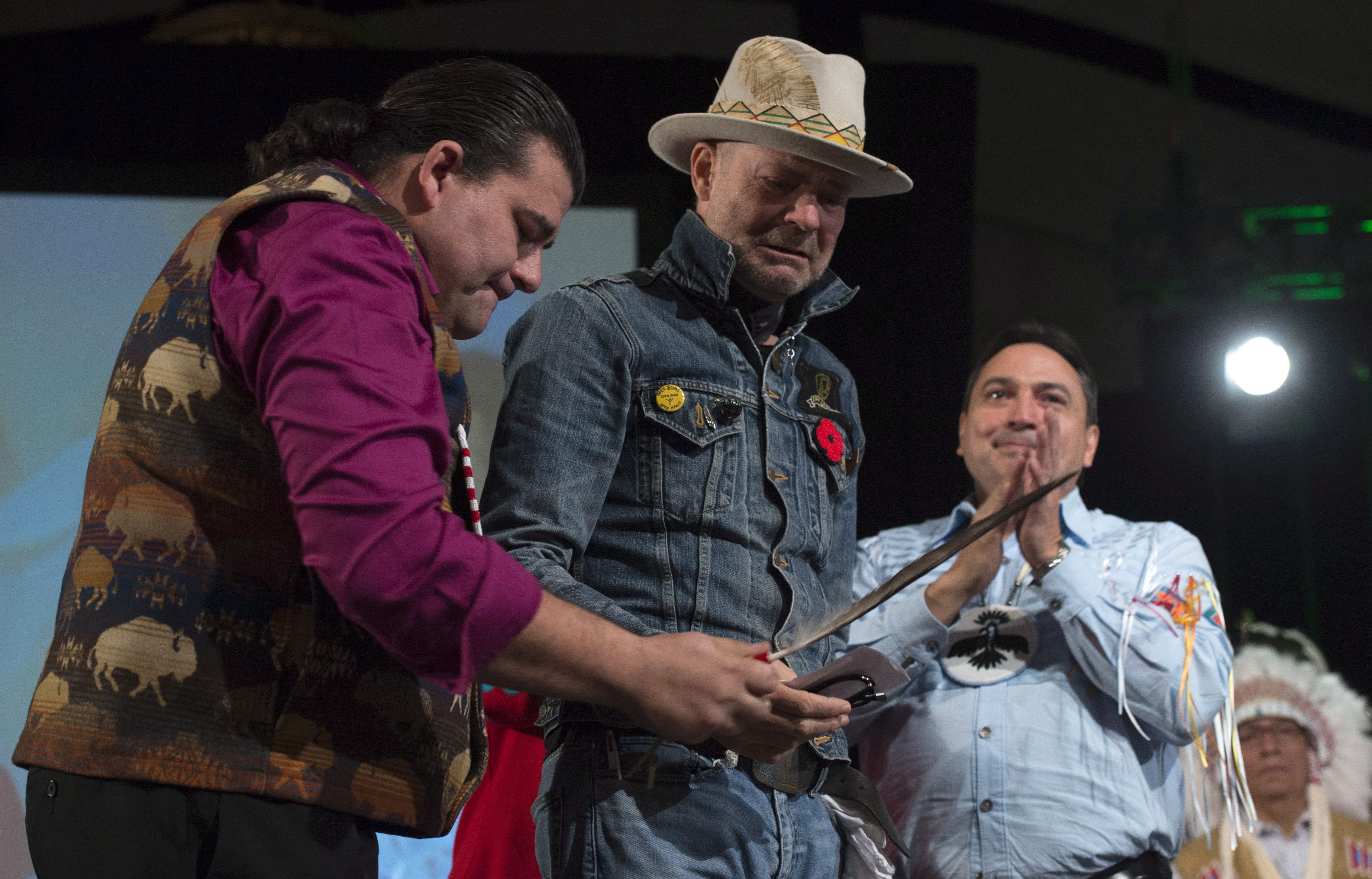

I was here [in England], in my studio, watching it through the tears. To watch him break down, you felt his pain. Everyone in that room felt the anguish and unfairness of it all. One of the worst things that can happen is knowing you only have so much time to live. That must be godawful. I don’t know how he could carry on. The best way about it is to go when you don’t know, because then you carry on in your merry old way. Then a few months later I saw the blanket ceremony [where Downie was honoured by the Assembly of First Nations], and I broke down watching that. I have a real thing about Native Americans, an amazing people with an amazing ethos. It brings it home just what a bunch of s–theads we were to these people all these years ago, and still are today.

Dave Clark: drummer in Rheostatics and Dinner Is Ruined

Relationship: Played drums in Gord Downie and the Country of Miracles, 2001 to 2010

I’d been watching it on my TV [in Toronto], and it sounded amazing in the house with the windows open. I went outside to see what the city’s doing. Everybody had their windows open. People all over my neighbourhood, no matter where I walked, it was like a living boom box. Then bars and cafés and courtyards on College Street were hanging bedsheets and projecting it outside. It was blasting out of wide-open doorways. It was amazing. And putting the Prime Minister on the hot seat in front of Canada—that was a really good thing. Whether you like the Hip or don’t like the Hip, man, you can’t deny that stuff. That night that they galvanized Canada. It was a really special national moment. I was glad to witness it. It made me cry.

Bruce Dickinson: former A&R executive

Relationship: Signed the Tragically Hip to MCA Records in 1988

I’ve had my own medical issues in recent years. That afternoon of the show, part of having been ill, I was very dizzy. I fell off a bus and landed square on my chin. I went into an ER at Columbia Presbyterian, a few blocks from where I live [in New York City], with a mild concussion and my shirt was covered with blood. They looked at me and said, “You’re going to need 14 stitches.” I looked at the doctor and said: “Here’s the deal. I have to be walking out of here at 7:30.” “What if we want to keep you here for observation?” “No. I’m walking out of here at 7:30. Do what you have to do so that can happen.” Because the show was going to start at 8 o’clock! I came home, kind of woozy, and watched the show on my Mac. It was very bittersweet. I was extremely proud of the guys. They were phenomenal. To see Gord Downie be able to summon what he did to do that show—my throat is catching as I describe it to you. It’s part of what makes him a great artist. He’s got that inner drive and that inner spirit.

I saw that right away, way back at [the first time I saw them, at] Massey Hall [in 1988]. This is a guy who will not be denied. That’s what you need. You need an artist who will grab you by the lapel and go, “I have something to say and you’re gonna listen.” And you could see the love and support from the other guys. When Gord might have been about to falter on some words, Paul [Langlois] could see it coming and he was right up there next to Gord, doing a harmony so the lyrics came through. [Rob] Baker and [Gord] Sinclair were watching Gord throughout the show, ready to do whatever needed to be done to support him. When they did the encores, Johnny [Fay] was literally carrying Downie down the steps at the back of the stage. All of that stuff added up to one of the most powerful things—if not the most powerful thing—I’ve ever seen on a stage.

Dale Morningstar: guitarist, Dinner Is Ruined

Relationship to the band: guitarist for Gord Downie and the Country of Miracles, 2001 to 2010

I was at [my spouse’s] mother’s house in Manitoulin Island. Her whole family was there: brother, stepdad, sister and her husband. We were all down in the basement. They knew I had an association with Gord, but they didn’t know how close. We’re watching it, and I’m saying, “The best part of it is when the band leaves the stage and Gord delivers a soliloquy. It’ll drive you to tears.” As soon as the band left the stage, there was a storm, and—boom—no signal. It was like, “Wait, what?” The timing was impeccable. The TV kicked back in for the last song of the last encore. I went out for a swim after, alone. It was still storming out. I was just yelling at the sky.

Ian Blurton: guitarist and singer, Change of Heart, Public Animal

Relationship: opened for the Tragically Hip multiple times, from 1991 to 1997

Not all of it, but I did watch it, yeah. I was at home. I thought they way they did it was great, and calling out Justin Trudeau was a stroke of genius. But it was hard to watch.

Steven Drake, guitarist and singer, the Odds

Relationship: opened for the Tragically Hip, 1994-95; mixed Trouble at the Henhouse (1996) and Music @ Work (2000); produced Gord Downie’s Coke Machine Glow (2001)

I kinda watched it and didn’t watch it. I’d just seen them a few weeks before in Vancouver. I had the broadcast on while I was doing other things in the house. I think I was building a telescope or something. I couldn’t sit there and watch it; it was too intense. But I couldn’t turn it off.

José Contreras: guitarist and singer, By Divine Right

Relationship: opened the Tragically Hip’s 1999 tour, played on Coke Machine Glow

I didn’t watch it. Friends of mine from Edmonton, the Wet Secrets, asked me to play a show at the Drake in Toronto. No one checked the calendar; we only realized 10 days before that it was the same night of the Hip show. I called the Drake and said, “Can we broadcast the show, 8-10, and then play our show after?” They said they had an event and couldn’t do it. I was really torn up. Then I realized I got this gig for the same reason I played with the Hip: because a friend offered it to me. I’m a working artist; that’s what I do. I don’t have management, a label, or a booking agent. I take what comes to me. It sucked, loading into the Drake, bumping into friends, who asked me, “What are you doing?” “Um, loading into the Drake.” “Okay, weird. Bye!” But you know what? We had a great show. Lots of people there. I took a picture of the Wet Secrets during their set, when they hit that moment when they were great. I remember thinking: this is worth it. This is music. This is life. This is my life.

Sam Roberts: bandleader, the Sam Roberts Band

Relationship: opened for the Tragically Hip more than any other act, beginning in 2002

One of my relatives from South Africa was here last summer when the concert was being broadcast on the CBC. We had a big party at another cousin’s house: brought the TV outside, speakers out. It was a very emotional time. I’m watching my cousin, who has never heard this music before, going, “What is this about? What am I listening to?” But after half an hour, 45 minutes, there was definitely the dawning of something [for them]—which to me suggests that [the Tragically Hip’s music] is not just this impregnable fortress, where if you’re not literally born to it that you’re not going to understand it. Whether it was the music itself, or the delivery, or the performance, or Gord’s character coming through. I don’t know what it was, but it left an impression.

The grief [for the rest of us] was very real. Very deeply felt. It was not a superficial grief in any way, and it was collective. I don’t know what people’s expectations were in terms of what they were going to see on that stage. The fact is the band went out once again and went far beyond even what I’ve seen them do before—in terms of the depth of their commitment on stage. Maybe we take it for granted because they’ve done it so consistently over the years. It takes a great deal out of you to be able to do that.

Bry Webb: guitarist and singer, the Constantines

Relationship: opened for the Tragically Hip in 2006

I watched it on TV. The most moving thing about it was Gord’s vulnerability and his response to his own vulnerability, or his own fight—the guttural release coming from him in moments of that set, and the look of peace and bliss and enlightenment on his face. Two minutes later, he would be bestial, just catharsis and release. It was everything I value about him and performance and art—it was all there. It was pretty punk, from five men kissing each other full on the lips before taking the stage, to watching him drop a few lines and be aware of it and just say “f–k it!” There was a lot of great punk rock energy to that show. The shout-out to JT was full of intent and was a really interesting decision. I read it as putting the pressure on. It wouldn’t make sense, in terms of the energy of that moment, to say “f–k you” about this issue. It was him saying, “Here’s some energy. I’m putting a spotlight on this at the moment, in a way that I can.” Knowing the intention with which Gord does things, I felt that was what was happening at that moment.

Kate Fenner: singer/songwriter

Relationship: backing vocalist on the Tragically Hip’s 2000 tour, one of only three guest musicians to have ever toured with the band in 30 years

I couldn’t do any of those shows. I didn’t see any. Just couldn’t. [My family and I] went to Greece and Malta. I was born in Malta, but I’d never been back. I was on a rock in the middle of the Mediterranean. I got a coffee and opened the paper, and—motherf–ker!—the Times of Malta had a huge picture of the last show. It was unbelievable.

Brendan Canning: co-founder, Broken Social Scene

Relationship: Opened for the Tragically Hip as a member of hHead in 1994 and as a member of By Divine Right in 1999; opened as a solo DJ during 2015 tour

I went to a Toronto show and thought it was sweet how tight they were on stage. And it was nice to hear new material as opposed to just all the old songs again. But the last show? I wasn’t interested. I’d been on tour with them in 2015. I’ve been watching them play since 1989. I didn’t need to see another Hip show. Everyone was talking about it, and I was like, ‘Yeah, yeah, I get it.’ I was in [the Hip’s studio outside Kingston], with Broken Social Scene that night. Kev [Drew] went to the show. I’m not one for fanfares of that regard. It’s a heavy emotional thing—which is the understatement of the year—but I don’t need to be there for it. Any chance I can be at the studio without a bunch of people around, I’m going to take it.

Shannon Cooney: choreographer

Relationship: Worked with Gord Downie on a dance piece in 2002

I watched it [where I live] in Berlin, where there is a six-hour difference, so it started at 2 a.m. I was worried I wouldn’t be able to watch it, because CBC video content is usually blocked outside the country. But then I realized I couldn’t miss this, and the CBC unlocked it. All of Berlin was sleeping while I watched this show until 5 in the morning. I danced in my living room. But then I was kind of emotionally destroyed for the next few days. It was hard to explain to my German boyfriend just how much Canada loves Gord and that whole band. They could have broken up long ago; Gord could have been a solo artist, but he’s a loyal member. What a show! It was political: he was talking about strong women, and he called out Justin Trudeau on our dirty, dark secrets that we didn’t all know we had until the reconciliation process. Music is present, but it’s also a marker of time. We went from the late ’80s until now with this presence, this poetry that you either completely love or you push up against because you don’t like it, but it runs through these generations. It has personal resonance; it’s not just about watching these people on stage.

Neal Osborne: guitarist and singer, 54-40

Relationship: Peer

In the 1980s, we were in Saskatoon at some festival: it was Spirit of the West, us, and Tragically Hip. I hadn’t seen them much until then; I knew they were starting to grow a following. It was really rainy. Spirit went on and it was drizzly and rainy and I felt bad for them. Then for some reason, for us the clouds broke and it was all nice and the sun was setting. Then a storm came in and just poured, and there was lightning, and Downie was out in front just givin’ er, and I thought, “Okay, I get it. This guy is committed.” That’s when I became a fan. I always think back to that gig, because both those guys [Downie and Spirit of the West singer John Mann, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s] have gone through some trials. [On the night of the Hip’s last show] we were playing in Saskatoon again, actually. We did a shout-out to them and then we managed to catch the last couple of songs in the hotel lounge; we finished our show early enough to do that.

Jim Creeggan: bassist, Barenaked Ladies

Relationship: Peer

I’d already seen one of the Toronto shows. I watched a bit of the final show on TV. I was on a family vacation, sleeping in a cottage on P.E.I. Down the way, some neighbours were blasting it. The ocean wind was blowing, and it was this ethereal Hip experience. It was good, because then I had time as I was falling asleep and listening to the sound blowing around, to process how I felt about it. It was a good time to reflect.

Jennie Punter: journalist

Relationship: Covered the band extensively in the ’80s and ’90s for the Queen’s Journal, the Kingston Whig-Standard, Impact Magazine

My husband doesn’t really like that kind of music, so we had plans to go to the Markham Jazz Festival to see Lonnie Smith that night. We had to eat first, so we went to a pub. They had the show on, and it was just starting. I could imagine what it was like to be in Kingston, because the Whig-Standard building used to be right there, off the square. I didn’t feel like I wished I could be there. But I was very emotional inside. I was with my husband and my daughter, so it was a very private thing for me.

It was a surreal experience: I was in a bar in a town I never go to, going to an event I’ve never been to, in a pub I’ll never go to again, in this festival setting with ice-cream booths and people tying balloons and all the stuff you see on a street closed to traffic. Then there’s this event that all of Canada is watching, and I’m not one of those people. It made me aware of how big an event it was. If I’d watched it at home alone in a room with the door closed, I wouldn’t have thought about that factor.

Virginia Clark: Kingston promoter, the Grad Club, Wolfe Island Music Festival

Relationship: Friend

I was sitting in the family section at the venue [in Kingston], and there was a lot of crying—pretty much non-stop for three hours. It was crying but also elation and joy, not just sadness. All the feelings! I’d never felt this way during any performance, ever, and how many shows have I seen in my life? Countless. I held on to that show for at least a week with melancholy. I was depressed and exhausted. I don’t know how to describe it.

Steve Jordan: founder and director, Polaris Music Prize

Relationship: At CKLC in Kingston in the late ’80s, he was the first DJ to play the Tragically Hip on Top 40 radio; MC’ed many early gigs

I don’t go back to Kingston often. My wife and I walked up and down Princess Street; every single place was blasting Hip songs. Went to Zap Records. [Owner] Gary [LaVallee] was playing some bootleg he had from ’88. The gravity of it was getting weird. Went to [Kingston venue] the Toucan for some pre-drinks. All the people I’d see at the shows all the time back then, that was their HQ. Right upstairs, in [a room once called] the Terrapin, was the first time I saw the Hip, capacity: 40. The reality of it started to kick in. I couldn’t help but drink.

When the band went into “Courage,” I thought, “This is the last time they’ll play this song—ever.” I collapsed. Started bawling. I felt like I was crying out of my pores. It was such a weird sorrow. I’d never felt anything like that before. Then the crying subsided and I tried to live in the moment. On that tour, I had a new appreciation for the band that I didn’t have before. They’re a proper f–king band, an excellent band. It’d be an easy show to have collapse around you, and those guys held it all up. Then I got sad again, cried out of my pores again. But it was definitely joy in the room. It wasn’t just undistilled sadness. It was every strong emotion in one cocktail. And I’m just a guy who sort of knows them, who was lucky enough to see the very early beginnings. That’s what was informing a lot of my emotion: “I’m not in the band. How are they even doing this? How did they do this for three weeks?”

Jake Gold: CEO, the Management Trust

Relationship: manager, 1986-2003

I saw six shows on the 2016 tour, including two in Vancouver and the show in Kingston. I hadn’t seen them play live since I [last] worked with them [in 2003], so: 13 years. It was great to watch them as a fan. It was good. It was interesting. While I think for others there was melancholy, I saw it as a celebration. I completely saw where Gord was coming from. He was saying goodbye to everyone he loved. That, to me, was how I walked in the door. It was really emotional, don’t get me wrong, but I didn’t shed a tear until the day after the Kingston show. Kingston was so beautiful the day of the show. It was everything you want for a Hip show: hot and sweaty and sunny out all day. The next day I woke up and it was pouring rain. I broke down and started to cry. But it didn’t happen until that day.

Rich Terfry, a.k.a. Buck 65: rapper and CBC radio host

Relationship: opened for the Tragically Hip in 2006, hosted CBC Radio broadcast of the Aug. 20 show

Through the night Gord is communicating in two different ways: with the microphone and his words, but with the rest of his body as well. I don’t know if what he’s feeling is being translated in that way, or maybe there’s something he’s taking from us that he’s reflecting back. I was never sure. I’ve seen Iggy Pop and Tom Waits and James Brown and Bruce Springsteen—I’ve seen them all live. But I’ve never seen anything quite like that, ever. It’s hard to imagine that I ever will.