American beauty: The outsider spirit of U.S. photography

As America debates who gets to be American, a new AGO exhibit is a reminder that America is made great by its outsiders

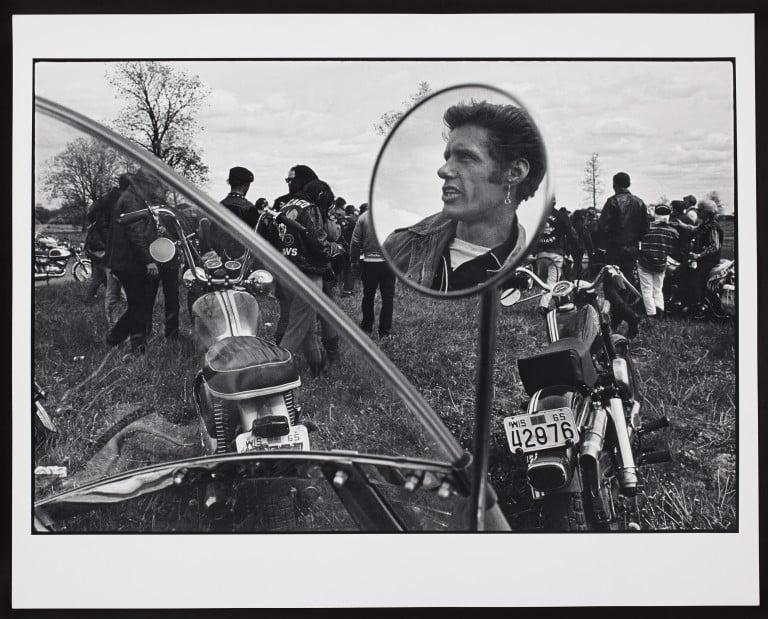

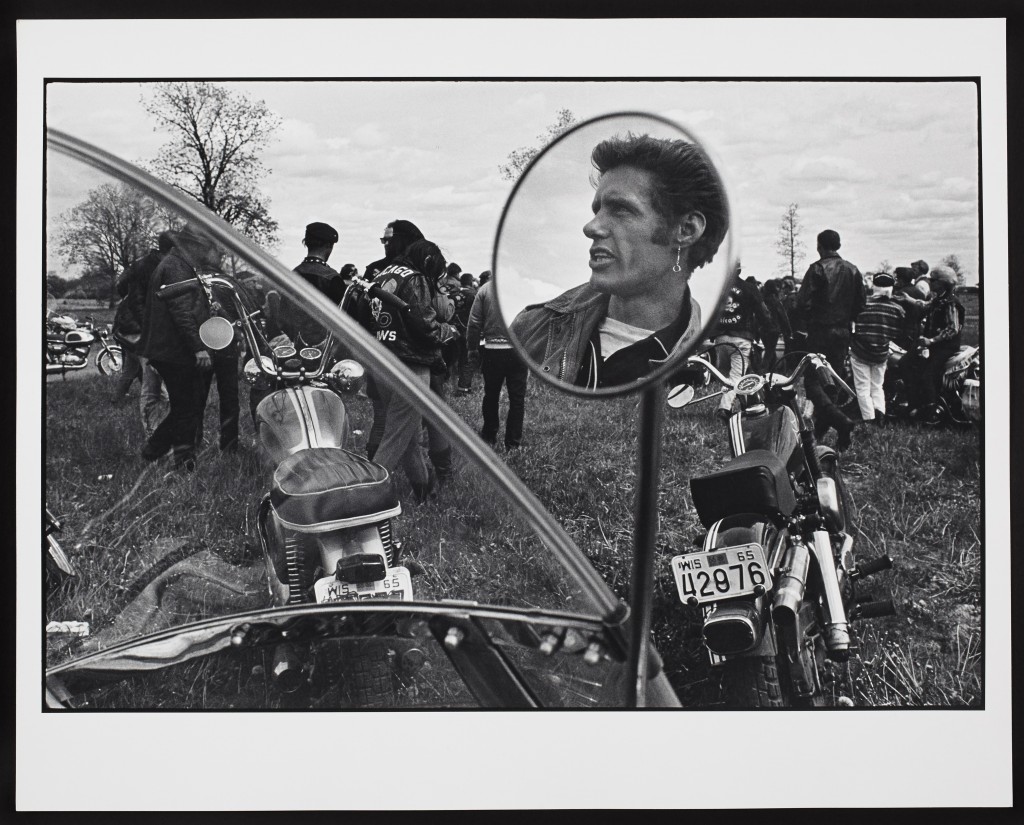

Danny Lyon: ‘Cal, Elkhorn, Wisconsin,’ 1966. Gelatin silver print, 40.6 × 50.8 cm. Promised gift, James Lahey and Brian

Lahey, in honour of our mother Ellen Lahey. © 2015 Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos.

Share

It is rare for outsiders to be comfortable becoming insiders. They’re supposed to stand at the periphery, staring cock-eyed at the establishment and the comfortable narratives it tells. If, as the painter Robert Motherwell says, art is necessary as the “examination of self-deception,” it’s important for artists to be outsiders—to jar us from easy truths, to cause clean lines to blur, to make us question our world.

And so it is striking that seeing the Art Gallery of Ontario’s new exhibit, Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s-1980s—a compelling and ambitious look at the essential American photographers who captured the oddballs and underbellies and miniature tragedies of the country’s fecund postwar period, from Diane Arbus to Garry Winogrand and beyond—is also seeing the works of the essential canon of American photography as a whole. All together, it tells an interesting story of its own: that the establishment of American photography is constituted of rebels, that American photography was made better by its outsiders—and that America was, too.

“These are the giants,” said Jim Shedden, the AGO’s manager of publishing, of the photographers and filmmakers featured in the exhibit he co-curated. “The technology and the time, and its contradictions—that you can choose to be free in America, but many chose not to be free—these photographers were responding to that, that culture of conformity and oppression and blandness.”

Lahey, in honour of our mother Ellen Lahey. © 2015 Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos.

It was a time of easy American narratives. The United States, puffed up and buoyant after its triumphal interventions in the Second World War, revelled in its new place as a true global superpower. That rise, many believed at the time, was achieved through the ethos of its American dream: that anyone could do anything through hard work amid limited social barriers. But the most toxic social barrier of all became that same American dream; it allowed figures like Joseph McCarthy to protect American ideals by defining themselves against who they weren’t—those damn Soviet commies—at any cost. America, between the 1950s and 1980s, was an ascendant, flush country that wanted you to be as American as you could be, but under a specific, paralyzing set of national values. If you decided not to follow them, you were un-American—and there could be nothing worse.

Photography became a major part of the telling of this rigorous American narrative. New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which culture author Fred Turner called “an extraordinary forum for the development of pro-democratic propaganda and for debates about what forms it should take” in the 1930s, produced the popular 1942 exhibit Road to Victory, discovering that photography was an ideal medium to subtly stir the American spirit. The MoMA followed that up in 1955 with the legendary Family of Man, which became a record-smashing success, the showcasing of lives through photos by artists like Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams. But by presenting largely white faces and the nuclear family, it advanced the myth of a singular, specifically American dream. Lange’s original callout for submissions sought to “reveal by visual images Man’s dreams and aspirations, his strength, his despair under evil”; the exhibit was sponsored by the U.S.I.A., a diplomacy arm of the government. By exhibiting in 37 countries—to more than nine million people—it became a state-sanctioned act of soft power. “It was an American effort to use photography to try to normalize American values in an international context,” said Sarah Parsons, an associate professor at York University’s visual arts department.

And so, as artists do, American photography rebelled.

You can see it in Gordon Parks’s searing photos of a black family in 1960s Harlem, daring to have them published in Life—the leading magazine for white, middle-class America, a magazine that provided at least a fifth of the photos in the Family of Man exhibit, and an outlet that would not typically force its readers to reckon with the uncomfortable realities of poverty, literally staring them in the face. You can see it in the photos of Diane Arbus, whose artistic portfolio collapsed the line between the surreal and real, a carnival of marginalized people marching in front her lens. You see it in Danny Lyon’s striking photos of biker culture, his “New Journalism” photographs serving a clarion call for a style of American liberty that is today seen as rote cliché but was, at the time, subversive.

And you can see it in what may be the crown jewel of the AGO’s exhibit, a collection of photos from “Casa Susanna,” a secreted-away New York compound where men would come to cross-dress, to cavort, to photograph each other to give proof of an existence they knew was real but felt they had to suffocate to live in American society. “They needed to document the reality of their lived existence in order for that experience to be complete,” said Parsons. “Maybe there’s something particularly American about that, this sense of confirmation of reality.”

Then a funny thing happened on the way to rebellion. Through sheer talent and the searing imagery, the outsiders became the institutional names of their medium. Perhaps that was always going to happen; as Parsons says, photos that resonate the most are the ones that “use photography to give us an image we don’t necessarily have in our own mind, or that we’re not familiar with.” Indeed, seeing their work today is to see a truer vision of America—perhaps a more recognizable America—than the vision of nuclear families and tidy lives. Images like the ones from these outsiders have now been pulled to the centre of American life.

There is, too, something very American about this era of photography. Perhaps it comes from the legacy of those American MoMA exhibits; perhaps it’s in the muscular portraiture of these stark photos, of the brazen certainty in freezing a certain moment; perhaps it’s in the fact that America is today’s destination for people looking to train to become a photographer. Perhaps it’s the fact this was a fledgling country finding its footing whose adolescence was being documented like all the firsts of an infant, and by being documented made the narrative realer, like the photos from Casa Susanna. Or perhaps it’s in the way that this America was able to reflect the world at large: “I think it’s … a place that’s very well-suited to photography in that it seems kind of class-less,” says Parsons. “It has both high and low, it can speak to historical moments, it enables us to articulate totally different positions and see them all together.”

Certainly, America doesn’t have a monopoly on contemporary photography—the medium’s fertile heritage in Europe contradicts that possibility—and it is not the sole American art form, given the existence of abstract expressionism, jazz, and hip-hop. But seeing the work of these photographers is simultaneously a chronicle of the blossoming of America and the blossoming of an art form—and it’s hard to see them as distinct.

What does it mean when outsiders critiquing the idea of America becomes the American institution? It makes it all the more powerful, more inclusive—and reforms the story that America tells. It means something, too, that this American art form, constituted by these outsider visions, is created by outsiders themselves; nearly all of the artists featured in the AGO exhibit are Jewish immigrants, or first-generation Jewish-Americans, a community “that is deeply outsider, not by choice,” says co-curator Shedden. And it means something that arguably the defining photographer of the U.S. is Robert Frank, whose seminal work The Americans collected elegiac portraits of his pan-American road trip (and whose influence suffuses the AGO’s exhibit)—but he isn’t even American, having been born and raised in Switzerland.

The idea that there is something very American about photography makes Outsiders, then, a surprisingly timely exhibit. These days, America has found itself wracked by division, its politics obsessed with Mexican migrants, Syrian refugees, and debates over who gets to be an American. A return to order is needed, its politicians promise; America must be restored to its former lustre. But as the leading American artists in a leading American art form shows, it took a collective of outsiders to make America great in the first place. And, maybe, once again.