Could art forgeries be even better than the real thing?

Art forgers not only turn themselves in, they have lucrative careers even after conviction. Just ask Michelangelo.

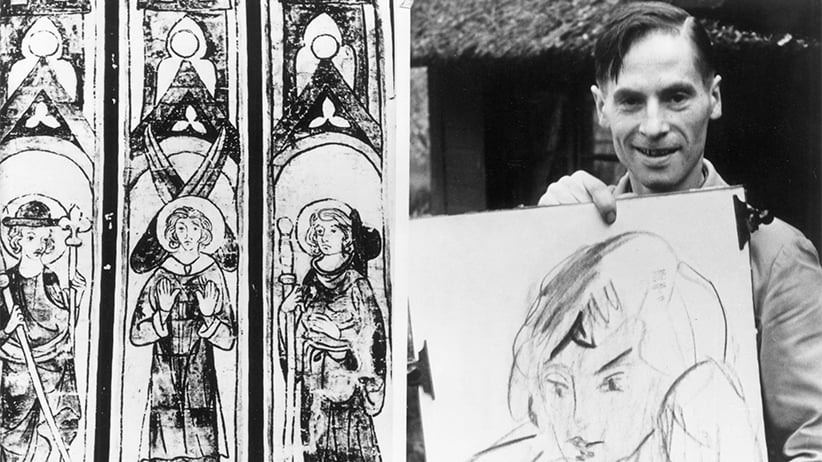

HANS VAN MEEGEREN (1889-1947). Dutch painter, art-restorer, and art-forger. Photographed 1946-7. (ullstein bild/Getty Images)

Share

Are you an artist, a struggling, grudge-filled artist? Do you have technical abilities of a high order, but come up a little short on the inspiration side? Do you enjoy extracting money from uber-wealthy patrons and—perhaps even more satisfying—shredding the reputations of experts? Are you willing to accept a little light punishment for a life of material comfort and artistic recognition? If so, the art world, more than ever, has a well-trod career path open for you. “There’s no other economic crime,” says Noah Charney, author of The Art of Forgery, “where you can be proud of the crime even after being caught, or have so lucrative a career—in the same field—after you get out of prison.”

The monetary incentive for art forgery is obvious. Most of the market value of an art object is tied to the story we can tell about it. Which is why a known fake, with its own compelling story about how it was created and how it fooled the experts, can also acquire value. Charney, the founder of the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art, notes how a teenaged Michelangelo got his start in the 15th century faking antiquities for Renaissance collectors, statues that started off as valuable because they were thought ancient, became worthless when revealed as forgeries, and became valuable again when the owners realized they were by Michelangelo.

Related: Teddy bear nitpick: The mystery of the Beaumont Bear

Small wonder that large-scale and often lucrative fakery is common. Geert Jan Jansen, who forged works by his Dutch compatriots in the 1970s and ’80s, made a fortune that investigators had trouble estimating—because his embarrassed victims were reluctant to come forward—but which was large enough to keep him in a spectacular castle adorned with genuine masterpieces. New York art dealer Ely Sakhai took to buying paintings valued in the six figures, and thus not headline-making works, and having them copied by a workshop of Chinese immigrant artists he maintained in the garret of his gallery. Sakhai then sold the copies in Asia and the originals in the West, hoping the twain should never meet. They did, though, in 2000, when the new owners both consigned their Vase de Fleurs by Gauguin for sale at the same time—the real one to Sotheby’s and the fake to Christie’s. The auction houses had a chat with each other, and Sakhai, whose estimated profits amounted to $3.5 million, went to jail.

But mercenary motives do not top the list for most forgers, says Charney. “Many want recognition. They have real skills and tried hard to make their own successes, before turning to fakes and the multiple benefits they derived—proving to themselves they were as good as past masters and showing up the critics who had ignored their own works.” And because the revenge is incomplete until the truth of what they see as their accomplishments is known, many make sure they are caught. Even if the art world is too oblivious to notice and they need to confess, one way or another.

Take Lothar Malskat, hired to repair bomb-damaged medieval frescoes in Lubeck, Germany, in 1948. He painted a whole new set while he was at it, frescoes he successfully passed off as part of a discovery made during his repair work. To eventually prove his responsibility, Malskat embedded what would later be called time bombs, anachronisms that would prove an art object couldn’t date to its purported time. In his case that meant portraits of a turkey (unknown in medieval Europe) and actress Marlene Dietrich (1901 to 1992). But such was the investment of experts and the client—the West German government printed four million celebratory stamps—that Malskat was ignored when he confessed. Incensed, he sued himself in court and eventually received a 20-month sentence.

The forger emerged from prison and began a new, comfortable living selling “original Malskat forgeries.” After all, it’s the story that that sells the art.