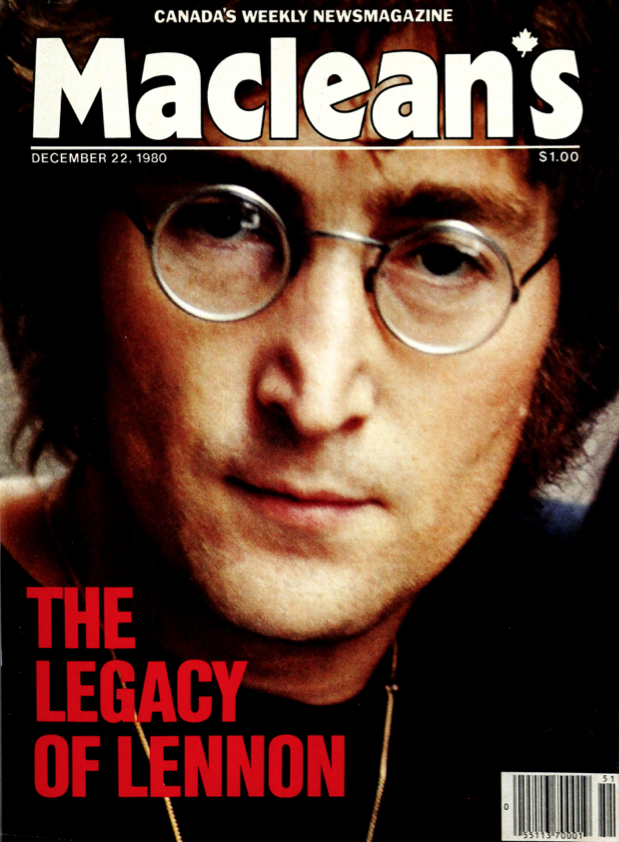

From Maclean’s, Dec. 1980: The legacy of Lennon

On Dec. 8, 1980, John Lennon was assassinated outside his own home. From the archives, Maclean’s reported on the scene at the Dakota, and Lennon’s enigmatic life

Share

Dec. 22, 1980’s issue of Maclean’s brought news that would not look out of place in 2015. “Gun-control debate intensifies.” “Springsteen, born to win.” “Pop psychology hits AM radio.” But at the top of the table of contents, its shocking cover story: the brutal assassination of John Lennon, as he walked into his New York City apartment building.” The former Beatle was assassinated on Dec. 8 35 years ago, and Maclean’s entertainment critic Lawrence O’Toole was outside the Dakota apartments where Lennon lived and fell. Here is O’Toole’s story, from the archives, replicated in full.

Dec. 22, 1980’s issue of Maclean’s brought news that would not look out of place in 2015. “Gun-control debate intensifies.” “Springsteen, born to win.” “Pop psychology hits AM radio.” But at the top of the table of contents, its shocking cover story: the brutal assassination of John Lennon, as he walked into his New York City apartment building.” The former Beatle was assassinated on Dec. 8 35 years ago, and Maclean’s entertainment critic Lawrence O’Toole was outside the Dakota apartments where Lennon lived and fell. Here is O’Toole’s story, from the archives, replicated in full.

“I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together.”

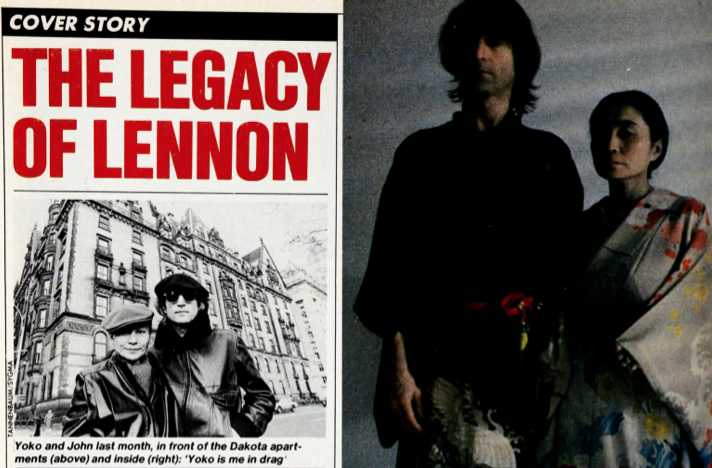

Outside New York’s Dakota apartments on the day after the assassination of John Lennon crowds have gathered in the December damp. Police barricades are up, unnecessarily: people are walking around, some of them carrying flowers, others merely wearing a lost look. Nobody knows what to do or say. Some of the flowers end up strewn on the ground, some are painstakingly attached to the iron gates of the Dakota. Except for the loud hum around the block, which is the noise of New York in the middle of the afternoon, the only sounds are those of songs coming from radios or tape players: a snatch of Imagine, a bit of Back in the USSR. In the centre of the Dakota’s iron gates is a picture of Lennon wearing the granny glasses that became as recognizable as Gandhi’s.

Later that night, a couple candles flicker in the rain. All the old youngsters are still wandering, desultory, forlorn, strangely vigilant. Lennon’s widow, Yoko Ono, had sent down a note in response to all the tributes asking the mourners to “pray for his soul.” But the crowd is still there, still not knowing what to do with themselves. Some have travelled from as far away as Brazil; some will wait out the night. A few voices quietly take up the strands of a snog from a radio. Hey Jude, don’t make it bad … And in the swell of the gathering a momentum emerges as other voices chime in and rise … take a sad song and make it better ….

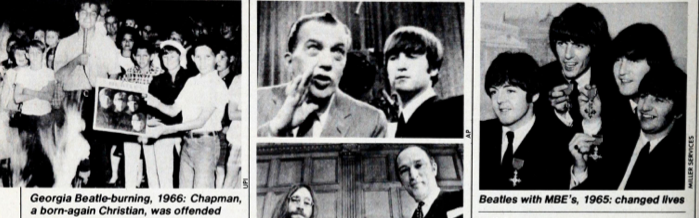

For the generation who discovered that hair covering a fraction of the ears could be subversive and that music could be a shiny political tool as well as a toy—and who had forgotten about it for a while—Lennon’s murder was a rude reawakening. John, Paul, George and Ringo (“And now for the youngsters—the Beatles,” Ed Sullivan once said) had changed the lives and dreams of a generation through music that grew in sophistication but never became remote—not even a decade later. “That guy with a gun stole away our childhood when he shot Lennon,” said Bob Geldof of The Boomtown Rats, one of the new bands of the ’80s, the inheritors.

The watchers outside the Dakota echoed that sentiment as the death of the man who wrote songs for all the lonely people led them all back through time. “I feel that he was a part of my life. I’m going to stay here as long as my feet hold up,” said Tara Gerdes, 22. “I always thought I’d marry a Beatle.” The man standing next to her, Jack Shea, 27, added: “He [the killer] killed a big part of me.” Although not part of “the Beatles generation,” Brad Durrell, 20, is nonetheless moved. “Lennon stood up for what he believed in. That deserves tribute. Some of the older guys at the office today were just walking around red-eyed and in a daze. It was unbelievable.”

Unbelievable. The biggest slap in the face the world can offer: mortality—made known to millions, its reasons comprehended by none. The Kennedys, King, Lennon. All of them leaders of thought and spirit, the last an artist, an incredible target for an assassin’s bullet.

“Was she told when she was young that fame would lead to pleasure?”

In self-imposed exile from the press and the public gaze since 1975, Lennon spent his time sequestered in domesticity as a “househusband,” baking bread and babysitting his five-year-old son, Sean. His wife, Yoko Ono, 47, vilified by fans as the whore of Babylon who broke up the Beatles, looked after their business interests (Lennon left $30 million in his will.) Having sat-in, bedded-in and dug his heels in for peace at the height of the Vietnam War and having fought a deportation suit by the U.S. government, he retired from recording. He didn’t have anything to say. Unlike other rock stars of his era who didn’t have anything to say, but said it a couple of times a year with new albums, Lennon would remain silent.

Meanwhile, documents of his and Yoko’s business acquisitions—five co-operatives in the Dakota, six sprawling country estates and, comically, for a couple who had been so politically attuned, big expensive dairy cows—found their way into the papers. Some fans consoled themselves by ruminating on the rumours of the Beatles’ return: there was even consolation in the possibility that John and Yoko might be doing an album any day now. John Lennon was invisible, but omnipresent. All this was beautifully articulated by a November Esquire cover story in which the reporter told of his defeated efforts to track Lennon down. That there wasn’t a single quote from the guru of peace and living musical legend didn’t matter; Lennon on the cover and Lennon’s elusiveness would sell copies. Then rumour finally became reality, and John and Yoko’s new album, Double Fantasy, was released, soaring to the top of the charts. As Lennon was emerging artistically and perhaps emotionally from his five-year-old cocoon in the Dakota, he was gunned down at the entranceway to the courtyard while returning home from the recording studio. The man charged with his killing was a former adoring Beatle fan, 25-year-old Mark David Chapman.

Before Double Fantasy was released, Lennon and Ono granted several interviews the most revealing of which was one in the January, 1981, issue of Playboy. “You’re like the typical sort of love-hate fan,” he told interviewer David Sheff, “who says, ‘Thank you for everything you did for us in the ’60s—would you just give me another shot? Just one more miracle?’ ” Lennon continued: “…people still had the idea that the Beatles were some kind of sacred thing that shouldn’t step outside its circle.” There was a reference to the “f—ing price of fame.” Hallowed and hounded, Lennon’s life outside the Dakota became a series of strained attempts to be normal. But the autograph hounds hung around the entrance gates waiting for him to return anyway. One of them was Chapman, for whom Lennon had signed an album earlier in the evening. It wasn’t enough.

It never is. The divine right of the devoted fan in this era is one of pursuit, and possession. A glimpse, a snap, a scribbled signature. Living in a society that constantly courts celebrity (running the gamut from People magazine to Andy Warhol’s Interview) and nursed on the notion that privacy is an unforgivably selfish act, the devoted fan assumes that right. “The king,” said Lennon, “is always killed by his courtiers.” The courtiers and the curious alike outside the Dakota kept their vigil for days, some of them cool, if not hostile, to the press. Lennon had hidden from the press, therefore the press was not welcome.

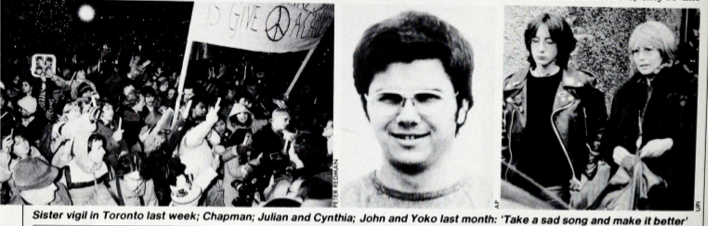

Lennon’s death ricocheted, turning into the “event” it could not help but become. Beatles fans made death threats to the owner of the store in Honolulu where the murder weapon was bought. Chapman’s court-appointed lawyer—who claimed his client was “nuttier than a fruitcake”—quit the case after receiving several death threats. The British press blamed New York, calling it “gun city.” STOP THE AMERICAN HANDGUN WAR said posters outside the Dakota, and suddenly gun control has become a major issue again (see page 30). Two despondent Lennon fans—one in Florida, one in Utah—took their own lives. Fifteen thousand people gathered at a sister vigil in Toronto and when the celebrities arrived, heads craned. “Oh, look, there’s Ringo,” said someone outside the Dakota. George and Paul never did show up to pay their respects. Double Fantasy couldn’t be bought for love or money—100,000 copies were sold in Canada on Tuesday alone—and record stores couldn’t keep Beatles’ albums in stock. There was hushed talk of the eeriness of the Dakota, where Rosemary’s Baby was shot, to lend the event an even greater aura. When Lennon was cremated on Wednesday, three decoy cars were necessary to foil those who would follow him to his grave. By Thursday, Yoko had asked that the vigil cease, having already requested 10 minutes of silent prayer for Sunday. TV stations flashed pictures from Mark David Chapman’s high-school yearbook, showed the place where he last worked, displayed reasonable facsimiles of the gun he had carried. Despite radio stations such as Toronto’s Q107 refusing to mention his name, Mark David Chapman will have the 15 minutes of fame promised by Andy Warhol to everyone—and more.

“He’s a real nowhere man,

Sitting in his nowhere land,

Making all his nowhere plans for nobody.

Doesn’t have a point of view,

Knows not where he’s going to,

Isn’t he a bit like you and me?”

Lennon’s somewhat throwaway contention in a 1966 interview that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus Christ” resulted in Beatle-burning bonfires in the American Bible Belt. Chapman, charged with second-degree murder (only killers of policemen and prison guards and charged with first degree in New York State) was a born-again Christian raised in Georgia. A former roommate, David Moore of Chicago, has said that Chapman took great umbrage at Lennon’s old quote. But, according to his father, David Chapman, Mark “loved” the Beatles. “He collected every album they’ve ever made.” (His collection grew so mammoth and collecting so consuming that his parents forced him to sell it.) Clearly, before he came to New York and checked into the 63rd St. YMCS on Dec. 6, Chapman was suffering some kind of identity crisis. As he left his job as a security guard and maintenance man, he taped over his identity badge and signed out as John Lennon, which he then drew a line through. (Like Lennon, he also married an older Oriental woman.)

Chapman was a drifter who had twice attempted suicide, was into the drug scene heavily before having a breakdown and, like many of his generation, had aspirations of becoming a musician or a painter. A nowhere man. Within the society that produced him, he was the most humiliated of all—a nobody. “Chapman may well have resented Lennon’s success because he hadn’t gone very far in life himself,” said David Abrahamson, an expert on criminal behaviour currently writing a book on the Son of Sam killings. “He may very well have wanted to kill himself and, not having the courage, chose the closest substitute—Lennon.”

Lennon himself may have been more astute when he said that “people got hooked on the teacher and missed the message.” The iconography of idolatry, the acquisition of relics such as snaps and autographs, adopting the physical style of the leader-guru were all part of an avocation Lennon found “naive.” The essence of his Playboy interview can be boiled down to a single quote: “Produce your own dream.” Lennon’s five-year exile could have been construed by some as a form of betrayal, abetted by the exaggerated reports of his incredible riches. The man who had left a blaze on every tree in the ’60s was now silent. He wasn’t even being generous musically. He was a deserter. Thought it may never move beyond the realm of speculation, psychiatric reports notwithstanding, it may be that when Lennon stepped out into the world again, Chapman, who so closely identified with him, was surprised, confused and emotionally ambushed.

“Help me if you can I’m feeling down

And I do appreciate you being ’round

Help me get my feet back on the ground

Won’t you please help me?”

John Lennon, born in 1940 to working class Liverpudlians, spent a great deal of his life looking for the Lennon catchwords, peace and freedom. The driving philosophical force behind the world’s most popular musical group, he was always the first of the four to set foot on strange territory. He tried grass, claimed to have taken more than 1,000 LSD trips, sought the healing powers of meditation with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and, in 1970, underwent primal scream therapy with Arthur Janov. By his own admission, Janov and the Maharishi were sought out as father figures, his own father having deserted him and his mother when he was born. (The prodigal father attempted to return home to his son at the height of Beatlemania.) Lennon’s childhood was matriarchal and not particularly happy (he constantly referred to Yoko as “Mother”) and, in 1967, his acquired father, Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, died of an overdose of sleeping pills. He left his first wife, Cynthia, and their son, Julian, for Yoko in 1966. When Yoko kicked John out in the early ‘70s (“Suddenly I was a raft alone in the middle of the universe”), he hit the bottle with Harry Nilsson and Keith Moon as buddies in despair. She took him back 18 months later; retired in 1975, he devoted his time to his newborn son because “It’s owed.”

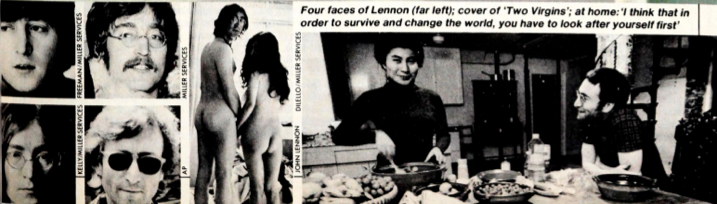

What purified Lennon in the eyes of many, more so than the other Beatles, was his willingness to try every avenue open to self-realization and his willingness to admit some of them were cul-de-sacs. He had the good sense not to fear making a fool of himself, therefore experiencing no humiliation or embarrassment. He and Yoko released Two Virgins in 1968 with themselves naked on the cover, and record companies refused to release it. He stuck a Kotex on his forehead in a restaurant and played the fool. He and Yoko held a public honeymoon in their bed in Amsterdam in 1969. But the messages of love, peace and freedom, as simplistic as they might have sounded, needed no decoding and seeped into public consciousness. However, the wingy messenger himself had more impact: in these times, the icon seems more tangible than the prayer that dies a quick death.

Lennon was, in some instances, a deep contradiction. The man who wrote Working Class Hero led a cushy, if confined, life in the Dakota. An incisive and clear thinker, he nonetheless attributed magic powers to the Egyptian antiques he collected. A very rich man by any standard, he said that he and Yoko “feel more comfortable now”—though they did set aside 10 per cent of their earnings for certain causes, one of which was bulletproof vests for the New York City Police.

“Is there anybody going to listen to my story

All about the girl who came to stay?

She’s the kind of girl you want so much it makes you sorry

Still you don’t regret a single day.”

As overwhelming a cultural force as the Beatles were, John and Yoko became a union to be reckoned with. They produced a blush on the world’s fair complexion by proclaiming how much they loved each other, and how that was so right, from under the sheets of hotel beds around the globe. Yoko, who played the straight man, hardly ever smiled: John, with an alternately droll and sassy wit, did the original fool on the hill. They were playing high mass on a kazoo.

“Yoko,” said John, “is me in drag.” For others she was the dragon lady, a distaff Svengali, a conceptual artist who influenced John’s music to its detriment. When the Beatles broke up in 1970, Yoko was generally blamed and there was talk of death threats. Several weeks ago, she said: “Those hate vibes, they’re like love vibes, they are very strong. It kept me going. When you’re hated so much, you live. Hate was feeding me.” A confirmed pacifist until he died, Lennon, ever changeable, changed his mind once again, stepping onto new ground inside the Dakota: “I think that in order to survive and change the world, you have to take care of yourself first.” In the end, devoted to his life with Yoko, Lennon had taken care of himself very well. He recently said: “If Yoko died, I wouldn’t know how to survive. I couldn’t carry on.” Some of those left behind felt forsaken, others merely got on with the business of life leading into the bleak ‘80s.

“You and I have memories,

longer than the road that stretches out ahead.”

The Cavern Cub where the Beatles first played is now a parking lot. Lennon’s death is a reminder of the promise held in the ‘60s, his new song, Starting Over, a renewal of a promise of a slightly different sort. After the shock of his death has passed, this is his legacy to the generations that held candles last week. Of his new music he said: “I hope the young kids like it as well, but I’m really talking to the people who grew up with me … Did you get through it all? Wasn’t the 1970s a drag, you know? Well, here we are. Let’s make the 1980s great because it’s up to us to make what we can of it.” That thought can be carried around, like a talisman.

—With files from Rita Christopher, Jill Eckersly, Marni Jackson, Ann Johnston and David Livingstone