Gord Downie’s not-so-Secret Path to truth and reconciliation

Everything about it—the music, the film, the band, his performance—makes you want to pay attention

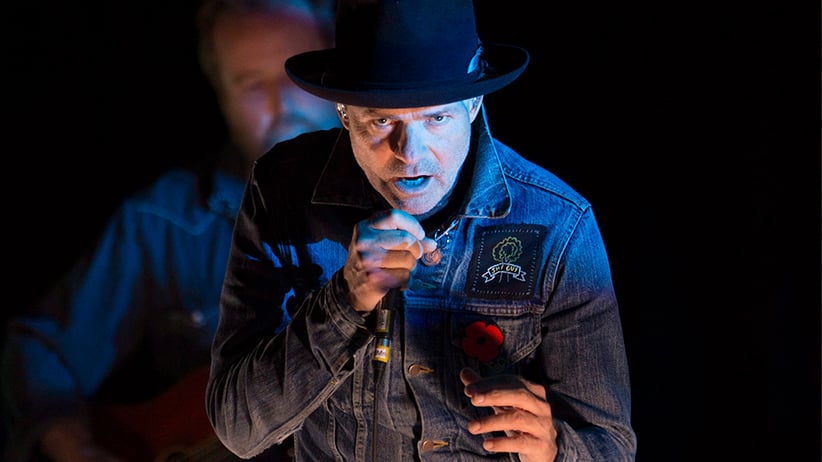

Gord Downie is seen performing part of his solo project, ‘Secret Path’ at the National Arts Centre, in Ottawa. The album is a collection of songs which tell the story of Chanie Wenjack, who died fleeing a residential school 50 years ago. (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

It was white guilt night for the Toronto elite, some of whom paid $1,000 (for something called Gold Circle Tickets) to spend their Friday night at Roy Thomson Hall watching a man dying of brain cancer sing songs about a boy who died trying to escape residential school 50 years ago.

The event was the release of Gord Downie’s Secret Path: an album, graphic novel and animated film that tells the story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old boy from Ogoki Post, a tiny fly-in community halfway between the vast expanse of Thunder Bay and Attawapiskat, territory that’s all but invisible to most Canadians, even more mysterious than our Far North. Downie’s older brother, Mike, discovered Wenjack’s story in a 1967 Maclean’s story, which has since spawned a small cottage industry that has transformed the powerfully symbolic—but until last month, completely obscure—story into practically as much of a household name as Alan Kurdi was in 2015.

One can’t deny the role of Downie’s terminal condition in all of this: interest in new Tragically Hip albums waned considerably in the last 15 years, and only diehards seemed interested in following his (highly underrated) solo records. Then came the summer of 2016 and the massive outpouring of affection for Downie and everything he’s built in our tower of song.

And so if Gord Downie wasn’t in acute danger of disappearing, of investing his final days in a cause that rails against the albatross of facile nationalism hung around his neck, would anyone be interested in his solo project about a long-dead “Indian” boy? With last year’s conclusion of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the time is ripe for non-Indigenous people to be receptive to this particular tale of gross negligence that’s indicative of a larger stain on Canadian history. Mike and Gord Downie admit that as recently as just a few years ago they were ignorant of the horrors of residential schools, of unmarked graves, of the Sixties Scoop. As role models for a new “woke” white Canada, they’re doing plenty of heavy lifting.

One could choose to be cynical about “white saviours” fetishizing Indigenous tales of woe as a way of processing collective guilt. One could choose to speculate how many people at the Roy Thomson Hall show were even aware that this week Toronto is hosting its annual celebration of thoroughly modern Indigenous visual media and arts, ImagineNative. Or one could embrace the fact that Canada is finally having this conversation at all. After all, which side needs to do the reconciling here?

The evening began with brief remarks from Mike Downie, the filmmaker, who promised that we would all “be a part of history and reconciliation tonight.” That’s setting the bar pretty high. Gord and his ace band—keyboardist Kevin Hearn (Barenaked Ladies, Rheostatics, Lou Reed), guitarist Josh Finlayson (Skydiggers), bassist Charles Spearin (Broken Social Scene, Do Make Say Think) and principal musical collaborators on Secret Path, Kevin Drew (Broken Social Scene) and Dave Hamelin (the Stills)—entered and started playing the album in order, underneath a screen projecting the film (which is an extended, animated video devoid of dialogue or narration). The music is appropriately contemplative and atmospheric, rarely up-tempo; fans of both Downie and Drew could place it somewhere between Downie’s Coke Machine Glow (2001) and Drew’s Darlings (2014).

The lyrics, unsurprisingly for Downie, are not direct narratives. These songs do not tell a linear story. They do not document abuse. They don’t even specify geography. Maybe that’s to their credit. But out of context, a casual listener would never know what any one of these 10 songs is about. The words of the great poet may, in fact, be the weakest link in the project. The film, which is striking and beautifully done, also only makes sense if you already know the broad strokes of the story. What makes it effective is the whole package, and the fact Downie has thrown his weight behind it. Everything about it—the music, the film, the band, his performance—makes you want to pay attention and find out why this is so important to him. The onus is on you.

(Essay continues beneath the video)

What was most remarkable at the show was Downie’s voice: this was not the gruff, clipped rock’n’roll barker he is in most of his work both in and outside the Tragically Hip. On songs like “Seven Matches” and “I Will Not Be Struck,” he was going for the higher notes in his range and holding on to them with an almost operatic strength he’s rarely displayed before. In this setting, there were no signs at all that his body or his brain might betray him any time soon. That said, it was chilling hearing him sing the lyrics of the final song: “I feel … I hurt … I lived … I died … You sign / Here, here and here.”

Downie only addressed the audience once, before the penultimate song. “Let’s not celebrate the last 150 years,” he said, on the eve of this colonial country’s sesquicentennial. “Let’s celebrate our next 150 years.” At the end of the set, he looked at the Wenjack family—25 of them, Chanie’s four of his surviving five sisters and their descendants—and said, “Sorry family. This will get things going.”

Perhaps the evening should have ended there.

Instead, we were shown a short documentary about Downie visiting Ogoki Post to visit the Wenjacks, who thank him for bringing their brother’s long-forgotten story to light. Downie is gracious and largely silent; he knows this is not about him, even if the film doesn’t: in a situation where the pathos is more than obvious, we probably don’t really need to see scenes of Downie crying over Chanie’s grave. The lone heckle of the night (outside of two or three random calls to “Gord!”) was someone yelling, “Sorry, Chanie,” after the film’s conclusion.

Afterwards, MC Mike Downie introduced graphic novelist Jeff Lemire, animator Justin Stephenson and producer Stuart Coxe, who stood to the side like a trio of groomsmen beside the best man. Downie took that theme and ran with it, going on to introduce his youngest brother, then the band, and finally Gord, lauding him and laughing with him in a strange combination of wedding toast and funeral eulogy, concluding by telling him, “I’ve never been more proud of you than I am tonight.” Then we met the author of the 1967 Maclean’s article that started it all, Ian Adams. Nobody spoke except Mike Downie, lavishing praise on everyone present, and excited that the book and film were going to be used in education projects. His speech was punctuated by frequent applause. One half-expected him to channel a rock’n’roll preacher: “Are you ready to reconcile tonight?” (Note: not actual quote.)

Finally, 25 members of the Wenjack family took to the stage to an extended standing ovation; two granddaughters gave short speeches, and then Pearl Achneepineskum unleashed a river of tears in the audience with a traditional a cappella song—there was clearly room for more than one star on that stage. Finally, we listened on the P.A. to “Ashes of Love,” a country standard that was Chanie’s favourite song, one he would dance to with sister in the middle of the night, when he couldn’t sleep because of post-surgical pain in his lungs.

It was a beautiful, albeit odd moment, the urban crowd clapping along to a corny old country song in Roy Thomson Hall while we watched a Toronto creative team stand silently on stage beside an extended family from northwestern Ontario weep for a relative—whom many of them never knew—who died a tragic death, a death that has become a national symbol practically overnight, his long-forgotten life suddenly a metaphor for one of our greatest collective crimes. It was a remarkable collision of public and private pain, something Mike Downie noted that his family now knows something about first-hand.

But awkward though the evening’s denouement may have been, that’s also what real life is. Real life is not spectacle, not cool, not happy endings. It’s embracing total strangers and telling them you love them. It’s being there when people need you most. It’s living with your pain and soldiering on—if you’re lucky, you can transform that pain into art. Real life is corny country songs.

After Pearl Achneepineskum wiped her own tears and was embraced by Gord Downie, she said, “If Charlie’s life can save other children, then I’ve done my work.”

Gord wants the rest of us to get to work.