How Sarah McLachlan saved Run-DMC’s Darryl McDaniels

Mired in a profound depression, Darryl ‘DMC’ McDaniels explains how a Canadian singer became a ‘life preserver’

Jonathan Leibson/Getty Images for ELLE

Share

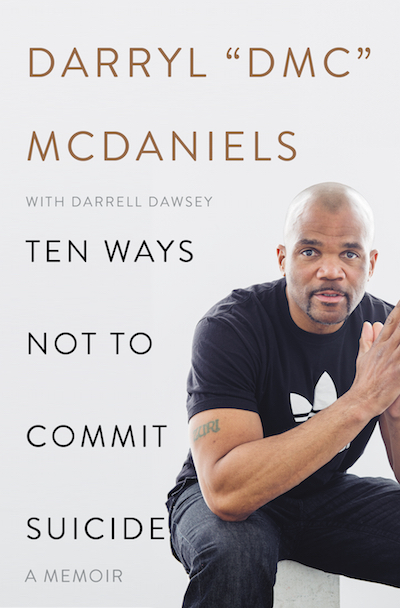

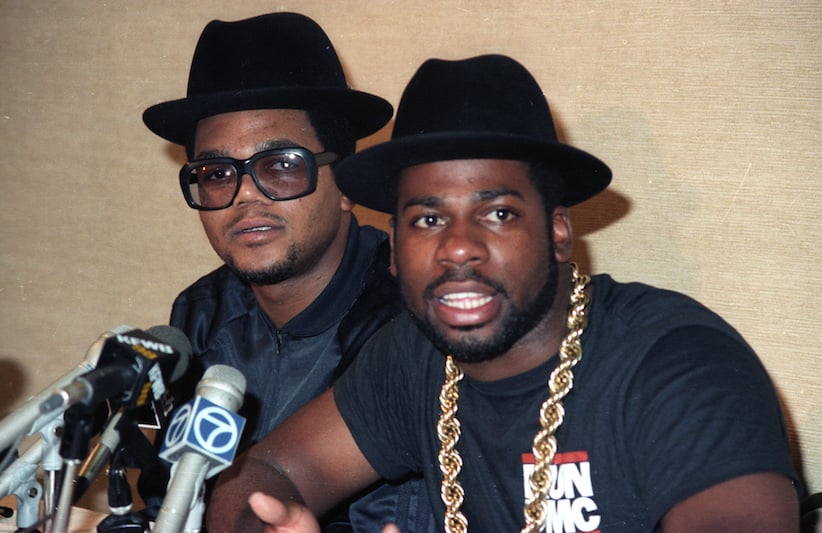

No one grows up being prepared for the wrenching despair of depression—not even if you’re a world-famous rapper. For Darryl McDaniels, better known as DMC from the legendary Run DMC—the highly influential hip-hop trio who were the first to have a gold album, a platinum record, and appear on the cover of Rolling Stone, and the second to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame —there was no guidebook on how to escape, no way to know how to find solace or salvation. He considered killing himself; he indulged in alcohol and drugs. But then, he found a potential way out—and it involved one Canadian crooner. In this exclusive excerpt of his new book, Ten Ways Not To Commit Suicide, McDaniels explains how he came across the music of Sarah McLachlan, how her song ‘Angel’ made him a huge fan—and how it saved his life. Read McDaniels’s long conversation with Maclean’s writer Adrian Lee here, about mental health, his story, and rap’s past and present.

No one grows up being prepared for the wrenching despair of depression—not even if you’re a world-famous rapper. For Darryl McDaniels, better known as DMC from the legendary Run DMC—the highly influential hip-hop trio who were the first to have a gold album, a platinum record, and appear on the cover of Rolling Stone, and the second to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame —there was no guidebook on how to escape, no way to know how to find solace or salvation. He considered killing himself; he indulged in alcohol and drugs. But then, he found a potential way out—and it involved one Canadian crooner. In this exclusive excerpt of his new book, Ten Ways Not To Commit Suicide, McDaniels explains how he came across the music of Sarah McLachlan, how her song ‘Angel’ made him a huge fan—and how it saved his life. Read McDaniels’s long conversation with Maclean’s writer Adrian Lee here, about mental health, his story, and rap’s past and present.

Most of us need someone to talk with as a form of seeking help. We need counselling, therapy. It is not a sign of weakness to seek help. Life is complex and subtle and insidious, in that problems often accumulate quietly, festering inside you for years sometimes before you realize how serious they’ve become. At the same time, to complicate matters more, changes are taking place within us all the time. If we’re not diligently scrutinizing, critiquing, and bettering ourselves, incremental damages can sneak up on us. But work hard enough, desire a goal enough, put enough pressure on yourself, and you can at least start the process of working through whatever troubles you.

I’m still trying to repair myself. I always will be, in a lot of respects. I work on myself in all aspects of my life, because being whole means just that—fixing all of you. Therapy has taught me that anger and resentment are like acid. Holding on to them just corrodes me from the inside. I can remember the long years of silently simmering at the world. Even when I was sober, I kept so many negative feelings pent up inside me that I felt weighed down every day. They weren’t just negative feelings about others. The worst of these feelings I often directed at myself. I allowed myself to be victimized by circumstances that I should’ve taken control of, but didn’t, and I became consumed with bitterness and regret.

After I shattered under the weight of my problems, I began the long process of piecing myself back together. Exercise helped. My counseling sessions with professionals like Wendy Freund were critical. But I also found relief in other, sometimes surprising, ways.

One example is how I ran across “Angel,” the song that, as I explained earlier, helped save my life. I had arrived home from a trip in 1996. I came out of JFK airport, got in the car, and the young-dude driver said, “Oh, s–t!” He was impressed that DMC was his passenger. The whole time he was driving, he kept peeking at me in the rearview mirror. When I’d look up at him, he’d turn his head like he was looking elsewhere. Eventually, we stopped at a red light and he fully turned around to look at me. “I’m not supposed to do this. I might get fired, but, yo, I got to take a picture. I love Run-DMC.” I never, ever have a problem with taking pictures with fans. I’ve always been grateful to anybody who listens to our music and appreciates what we do. “Sure, whatever you want.” We took a picture before continuing on our journey. I was quiet, caught up in my own world of problems, when the driver asked if it would be OK if he turned on the radio. (In fancy cars they ask. In ghetto cars it’s on blast before you even get in, and you have to yell for the driver to hear your requested destination!) I said, “Yeah, whatever.” He turned it to Hot 97, the hip-hop station. The last thing I wanted to hear was hip-hop. Since I couldn’t rhyme anymore, I didn’t even want to hear it.

MORE: Maclean’s interview with DMC, on rap, asking for help—and Drake vs. Meek Mill

The station had Busta Rhymes or Method Man or someone like that on. There was a bunch of people being interviewed on Funkmaster Flex’s show, and all of these dudes were talking about the commercialization of hip-hop. I couldn’t take it.

“Don’t turn it there, please,” I said. “Can you try something else? Anything else.”

He looked at me kinda funny at first—how the f–k does a rap legend not want to listen to the hip-hop station?— but then he obliged and turned it to this Lite FM station, WPLJ. The station often took me back to some of my earliest exposure to music on the radio, when I was a kid listening to Creedence Clearwater Revival and Harry Chapin. Now, though, it wasn’t those songs that touched me. The song that was playing on the radio was one that I’d never heard before, one that went right to my soul as soon as I heard it. It moved me in ways I had never been moved before. Oddly, as I wallowed in my own pain and sorrow and self-pity, it was just the song I needed to hear.

“Angel” is a piano record—dark and heavy. Right then and there, cruising through the bustling city, just home from Europe, I felt that song speak to me like no other. It felt like Sarah McLachlan had recorded that song specifically for me and I was meant to hear it at that very moment. I woke up the next morning with my wife at my side. “Hey, honey, you heard of Sarah McLachlan, that song ‘Angel’? I really like it.” I mentioned it to her because anything I say that I like, my wife likes to get it and surprise me. Sure enough, the next day I had the whole Sarah McLachlan album. Over the next year, that was the song I listened to every day, “Angel,” all day, on repeat. I listened to all the other songs on the album, “Building a Mystery,” this and that. Then I went out and bought everything she’d ever recorded.

For a whole year, every day I listened to “Angel” for almost the entire day. Wherever I was and whatever I was doing, the song was with me. Sometimes, I didn’t even want to leave my house for listening to that song. When the guys would come and pick me up for a gig, I had the song in my possession and they had to listen to it, too. When I got into the car I would tell my crew, “Yo, you got to play this,” and hand them “Angel.” After a while, Smith and Jay began protesting: “We ain’t playing that song!”

When they would refuse to play the song, I would turn around and walk back into the house. Erik, my manager, made them realize that I wasn’t joking around. “That motherf–ker’s serious, yo!” “All right, D. All right.” I’d sit in the limo, humming the song. They got sick of it, but I didn’t care. I needed that record.

It would be too simple to say that song got rid of all my negative feelings and pain and resentment, because that’s not what happened. It couldn’t rid me of the wounds or of that strange, inexplicable, gnawing void that was compounding all the hurt and rejection I’d endured. “Angel” was like a life preserver tossed to me in an ocean during a storm. It didn’t pull me out of the water, but it did help me stay afloat until other help came along.

I fell in love with “Angel” during my deep depression in the late 1990s, and several months after I first heard it I got a chance to actually meet the woman whose song had had such an impact on me. We met at a Grammy party thrown by the record executive Clive Davis in 1997.

Erik called me one day to tell me that he’d landed tickets to Clive’s bash, which was a very big deal in the music industry. He was excited about it, too, as tickets to Clive’s parties weren’t easy to come by, even for star recording artists. As excited as he was, though, I was equally as uninterested. I couldn’t have cared less about anything related to the music business at that point, especially not parties. The fame, the glamor, the money, to my mind, were all nonsense. Erik, who is usually a very laid-back guy, was audibly annoyed by my lack of concern. He and Tracey Miller, Run-DMC’s publicist, had pulled some pretty big strings to get those tickets. “Yo, D., you need to go,” he said. “It’ll be real big. Tracey Miller set this up.”

“I don’t care,” I told him. “I ain’t going.” “D., I worked real hard to get these tickets.”

Erik had to resort to explaining that he’d promised Tracey that I’d show up. I still acted like I didn’t care anything about it. Erik repeated his plea. “D., you don’t know how hard I worked to get these tickets. I told Tracey you were going.”

“You shouldn’t have told her that,” I replied coolly.

Erik has always stood by me, through some of the best and worst times in my life. Even before he became our manager, he used to tote around coolers filled with my 40-ounces. It wasn’t a high-profile job by any means, but he did it with the same seriousness and commitment that he does almost everything. Erik had paid dues and has remained a loyal friend, even when I’ve given him a hard time. For that, he has always merited my respect. Furthermore, he’s as business-savvy a dude as he is a devoted friend, which makes me listen to him when he talks, even if it takes me some time to come around. I knew that he was angry at me because of the way I was acting, but in spite of his being upset, he stayed after me about that party until the date finally arrived a couple of weeks later.

“OK, I’ll go,” I said. “But I’m only staying for one hour.”

“That’s fine with me,” he said. “All you have to do is walk the red carpet and take a couple of pictures.”

“I ain’t doing all of that, but I will go to the party.”

On our way to the opulent Beverly Hills Hotel, where the party was being thrown, I swore to him that I wasn’t staying longer than an hour. I meant it, too. I was supposed to sit at some VIP table, but I took a table near a back corner of the room instead. It was as close to the exit as I could get. As soon as I sat down, I glanced at my watch and began the minute-by-minute countdown to the moment when I could bounce. Fifty-nine . . . fifty-eight . . . fifty-seven . . . If I could’ve speeded up time, I would have gladly done so.

As the party picked up, the major stars who always attend Clive’s gigs filed in—Stevie Wonder, Alicia Keys, Busta Rhymes, P. Diddy, and the like. I stared around with an almost glazed look in my eyes. I was as unmoved as I’d been when Erik first invited me. Meanwhile, people were walking up to my table showing me nothing but love, telling me how young I looked and asking for the secret to my youth. I made nice, but in the back of my mind, all I could think about was going back to my hotel room, cranking up “Angel,” and reading books on metaphysics or something.

On my behalf, Erik was working the room, selecting particular media personalities who he wanted to have interview me on the red carpet. Usually, I was happy to talk to an entire pressroom full of reporters. This night, though, I probably spoke to maybe only three journalists total. That had to be some kind of all-time low for me. Then, minutes after I wrapped up my last interview and was about to resume my countdown, I looked up, and what I saw nearly made my eyes pop out of their sockets.

Sarah McLachlan had walked in.

Since I was near the door, I was the first person to see her as she strolled into the room. “Oh my God, that’s her,” I said, gasping. I couldn’t stop staring as she walked across the room, speaking with small groups of people.

I wanted to rush over to her, but I hesitated. Only a few people knew I was a closet Sarah McLachlan fan—and almost none of them were at this party. I thought briefly of how it might look to others to see the “King of Rock” fawning over a pop soloist. I quickly said, “Forget that.” This woman had helped save my life. As I saw that she was about to head into a larger room that was swarming with industry bigwigs, I feared that I might never get another chance to tell her what her music meant to me. Nervous and excited, I quickly made my way over to where she was standing. When I opened my mouth to speak, I sounded nothing like the swaggering rap superhero I projected onstage and in videos. My tone softened considerably.

“Excuse me, Ms. McLachlan,” I started meekly.

She turned around, saw it was me, and allowed a giant grin to spread across her face. “DMC? Oh, Run-DMC, I love you guys!”

Surprisingly, she began to actually rhyme the lyrics to some of our songs. It was a medley of Run-DMC classics. “It’s tricky to rock a rhyme/ to rock a rhyme that’s right on time.” “My Ahhh-didas walk through concert doors / and roam all over coliseum floors.” She sounded damn good, too. I was beyond flattered. I even thought, OK, that’s a good reason to stay alive. Sarah McLachlan likes my group’s music.

Jittery with nerves, my tongue drying out with each word, I continued: “That’s so cool, thank you. Well, Ms. McLachlan, I just want to tell you that one of your records saved my life. This past year I’ve been depressed and suicidal. I listen to that record every day. It’s the crutch that I stand on. I don’t leave my house without listening to that record. I don’t work out without listening to that record. I don’t travel without listening to that record. The name of the record is ‘Angel,’ and you sing like an angel. People say you are an angel, but you’re not an angel to me. You’re a god.”

I must’ve babbled on like that for more than two minutes. When I finished, I could see bafflement all over her face. Clearly, she hadn’t expected me to pour out my heart all over the floor in front of her at the hottest party of the year. I’m sure the poor woman simply intended to say hello, pay me a compliment, and keep it moving. She was gracious about it, nonetheless. She shook my hand, looked me in my eyes, and said, “Thank you for telling me that, Darryl—but that’s what music is supposed to do.”

I was overjoyed.

I will never forget that meeting.

Excerpted from Ten Ways Not To Commit Suicide, by Darryl McDaniels with Darrell Dawsey. Copyright © 2016 David Halton. Published by HarperCollins. All rights reserved.