Québécois music isn’t marginalized—it’s English Canadians who are missing out

How Quebec’s music industry has remained strong, prolific, and diverse, while also being unapologetically Québécois

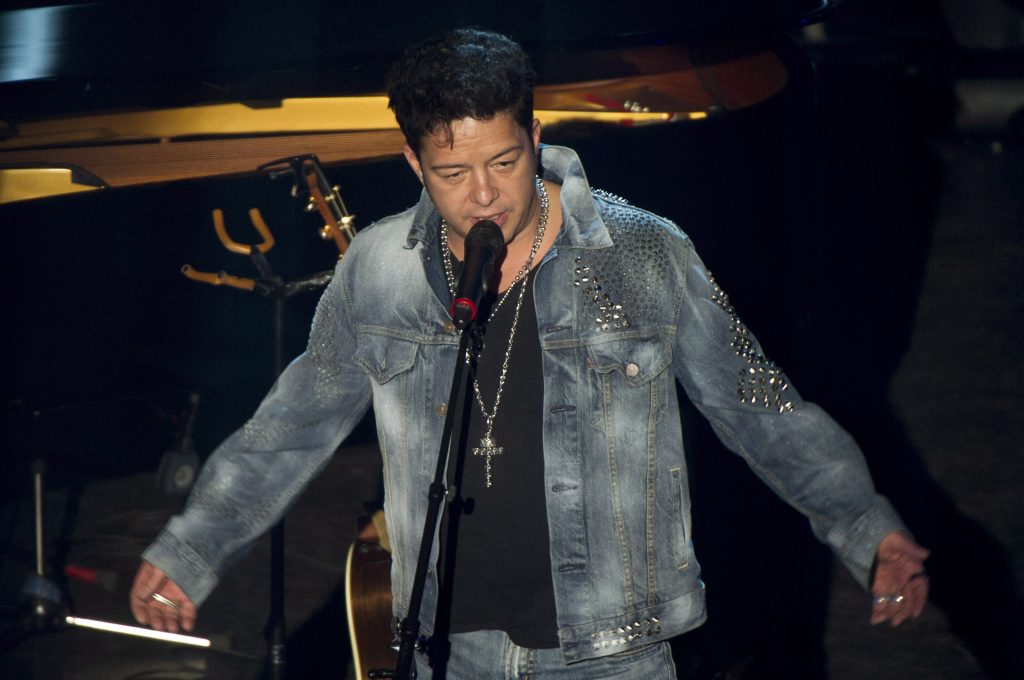

Hubert Lenoir performs during the Polaris Music Prize gala in Toronto on Monday, September 17, 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/ Tijana Martin

Share

The best Canadian-born performer going right now isn’t playing at Wembley Stadium or Madison Square Gardens, nor at Tokyo’s Nippon Budokan or Toronto’s Rogers Centre. He’s playing at places like L’Agora des Arts, a steepled brick building built in 1931 to serve as the first church in the Quebec mining city of Rouyn-Noranda, which hosts Festival de Musique Émergente. It’s since been converted into an arts performance venue, which is how Quebec City artist Hubert Lenoir came to be shirtless, slugging back beers and tugging on a cigarette, in the middle of a stage ringed by his band.

Lenoir, born Hubert Chiasson, is by any description a newcomer to the Canadian music scene. The 24-year old released a debut record, Darlène, earlier this year, and at first, it didn’t stir much attention. But Darlène, recorded in a Quebec City artists’ co-op, narratively set in Quebec City, and features just one song sung in English, has gradually elbowed its way to the front of not just Quebec audiences, but the consciousness of Canada’s Anglophone listenership: the record has landed him spots on Quebec reality show La Voix, CBC’s popular radio program Q, and the shortlist for the 2018 Polaris Music Prize; when he played at its annual gala on Sept. 17, it was his first live performance west of Quebec.

This fact presents two items of note. The first is that French-language music in Canada has long been underrepresented outside of Quebec. The second is that this circumstance might be changing—and that’s a good thing for all Canadians, no matter what language you speak.

Since its colonial beginnings, Francophone music in Canada has been at once borrowed, singular, and incredibly influential. The colourful instrumental reels and dance tunes of New France drew from Scottish, Irish, French, and English traditions, and still exist today as folk music standards on Canada’s east coast. Our national anthem was written by Calixa Lavallée, a French Canadian, 26 years before it was translated into English. Later, Quebec’s popular chansons style of music would emerge from the lineage of France’s chansons françaises, which feature a prominent vocal performance. But those chansons were driven by poetry and poignant lyricism as opposed to musical presence, which meant that beyond listeners who understood French, Quebec’s leading sound mostly fell on deaf ears.

This rift between French music and English listeners has only widened over time. Most Canadian music institutions are built around the English language thanks to pervasive social and geographical barriers. Canada’s vast terrain has made it difficult for bands from Quebec to break into markets west of their provincial borders, and communities with dominant French-language presences outside of the province are few and far between. In fact, it’s easier for Québécois bands who sing in French to travel to French-language countries in Europe, where they can play shows to bigger markets that aren’t so broadly dispersed and play to audiences who respect and share their mother tongue.

These factors have combined to create a sort of exclusionist English supremacy within the popular Canadian music industry outside of markets that are explicitly French. Although provincial and regional funding for French-language acts is indisputably strong, the JUNO Awards, the country’s premiere music awards event, still relegates non-English music to categories outside of the spotlight. And under the CRTC’s Commercial Radio Policy, French-language radio stations are required to play 65 per cent French-language pop music; Anglo stations, which naturally constitute the majority in the country, have no such language requirements. “No offence to anyone,” Bonsound Records founder Gourmet Délice chuckles drily, “but it’s a bilingual country, supposedly.”

Anglophones might assume that Québécois artists are the ones on the losing side of this equation, missing out on large Anglo-Canadian audiences in a time where Canadian pop and hip-hop superstars have put an international spotlight on the country at large. But in fact, it increasingly feels like English-language audiences and artists are the ones missing out on some of the country’s richest musical offerings, which can offer inspiration as Canadian music continues to evolve.

After all, Francophone artists hardly feel subjugated by English Canada’s oversight: Quebec’s music industry is booming and self-sustained. More than a third of the records that reached Canada’s Top 10 album charts in 2017 were from Québécois artists who performed in French, a higher percentage than any other province; only 800,000 more records were sold in Ontario compared to Quebec, even though the province has 5 million more people. And this week, veteran Quebec musician Richard Séguin’s new record sits at number three on the charts, behind only new records from Eminem and Paul McCartney.

This success is thanks in part to strong arts and culture funding programs that privilege French-language music as part of a cultural preservation movement, and national funding bodies like MusicAction and FACTOR are supplemented by provincial funding from the likes of SODEC, which provides a wealth of tour support, and Quebec Arts Council. “Sometimes big companies, big labels, they ask us, ‘What’s in the water here? Why are people still buying CDs?’ The support for the culture is so important,” Délice explains.

There’s also Quebec’s long-established vedette system, which lifts up Québécois artists and makes local celebrity a vaunted position, explains Martine Groulx, the president of indie record label Lazy At Work. “There are people who are famous here who nobody else in Canada has ever heard of. They can live off of their music, and there’s a lot of money to invest if you want to break into [the rest of] Canada.”

Take, for instance, Éric Lapointe, a Québécois rocker who’s released five platinum records, which denotes a record that has sold more than 100,000 units. Double platinum is reserved for records that sell more than 200,000 units, and two of Lapointe’s records have achieved that distinction. But, as Délice says, “he’ll never play a show outside of Quebec.”

But there’s another thing that’s changing: in Quebec’s music industry, as in major markets like Montreal and Quebec City, French and English are increasingly mixing. Veteran Montreal rapper Obia Le Chef performs in French, but when he started, he was rapping in English. “Most people wanted to rap in English because of the American influence,” he says. “Eighty per cent of the music that gets fed to us is Anglophone by default because of the market and the powers that be.”

Obia Le Chef notes that while there used to be a divide between Franco and Anglo rap in Montreal, younger MCs in the city are more likely to collaborate across language lines. “It was like a turnoff if there was a French hook and the verses are in English or vice versa… but I think now, more and more we’re seeing that type of situation where people mix up both languages,” he says. “I think that opening is more due to the fact that the younger crowd is more unified than the older MCs have been.”

“We live in a multicultural country. I think it’s a gift for all musicians to be able to play with other people that don’t speak the same language,” says Frank Lafontaine, a member of Montreal freeform rock band Klaus who also played in the Polaris Prize-winning Montreal indie rock group Karkwa. “When you say, ‘One, two, three, four,’ it’s not about the language. It’s about the music.”

That’s increasingly true because streaming, which has disrupted all parts of the music industry—even one that seems to operate in another era, with its vedettes and chansons and booming CD sales—has diffused the difference between English and Québécois songs.

“Because of streaming, [for] a lot of people, it won’t matter what language the song is in,” says Camille Poliquin, of the electropop duo Milk & Bone. “Half of the songs I listen to in English, I don’t understand the words cause of the vocal treatment. I can find out the meaning afterwards if I want to.”

Indeed, American writer David Turner recently opined that the streaming app’s incredibly popular playlists focus on curating experiences rather than music, and mood-setting doesn’t need to abide by laws of language. “There are some Francophone songs that show up on Spotify and Apple Music on English playlists,” notes Groulx. “Hopefully there’ll be more and more of that.”

That desire for more interplay between Anglo- and French-Canadian styles has also meant that vocals-first chansons are no longer the reigning musical format, says Sam Joly of Klaus. “The vocal is more [part of] the music, than just the lyrics with the music in the background,” he says. Délice agrees, citing Québécois rock group Malajube as a success story beyond the province’s borders. “Their vocals were mixed almost like as an instrument,” he says. “You don’t need to understand the lyrics to appreciate it.”

Lenoir, whose personality and compositions are as central to his music as his French lyrics, shares the sentiment. “I think that I see myself as a Quebecer in a different way than maybe a generation before me that was very into conserving the language,” he says. “We’re kids of the internet. We see ourself in the world different. There’s this thing with identity that a lot of people have because of mobilization, and I guess everybody’s kind of confused about who we are as a nation and as people.”

For Lenoir, Darlène was created with mixing cultures in mind; he simply wished for everyone to be able to enjoy it, whether they spoke the language or not. But still, he wanted the lyrics to remain untranslated, worried that the words would lose their poetry. “It’s just a thing of feeling,” he says. “I really believe that we get amazing as writers when we know how to be amazing in our own language.”

Still, individuals in positions of power in the industry have an opportunity to begin to reconcile the imbalance around Québécois music. It’s worth observing that when Anglophone institutions signal-boost French-language acts, their English-speaking constituents listen. The Polaris Prize is seen by many Quebec artists as putting in that work, and according to data from Nielsen Music Canada, in the week after their Polaris victory, Karkwa’s Les Chemins de verre sold more physical units in Canada outside of Quebec than it had in the five-and-a-half months prior.

But Groulx and others note that the Quebec scene isn’t competing to break into the English market, but rather working to uplift the whole culture. “The one thing that’s important to everyone is that people continue to listen to French music,” she says. “If Hubert is having success right now, that’s good for everybody else. Since we’re fighting to keep the culture alive, we have this way of kind of working as a team.”

This is perhaps the crux of Quebec’s music scene: it is a community that, perhaps more than any province in Canada, proves the artistic value and opportunity of fluid, supportive, cross-cultural creation. It is both unique and derivative, independent and communal, idiosyncratic and accessible, insular and open. In the crucible of all of these qualities, a truly compelling sound has emerged. It is up to Anglophones in Canada to listen in.