Robin Thicke and the tyranny of the breakup album

For too long, we’ve given breakup albums, however bad, a free pass. Robin Thicke’s ‘Paula’ may help us fall out of love with the genre.

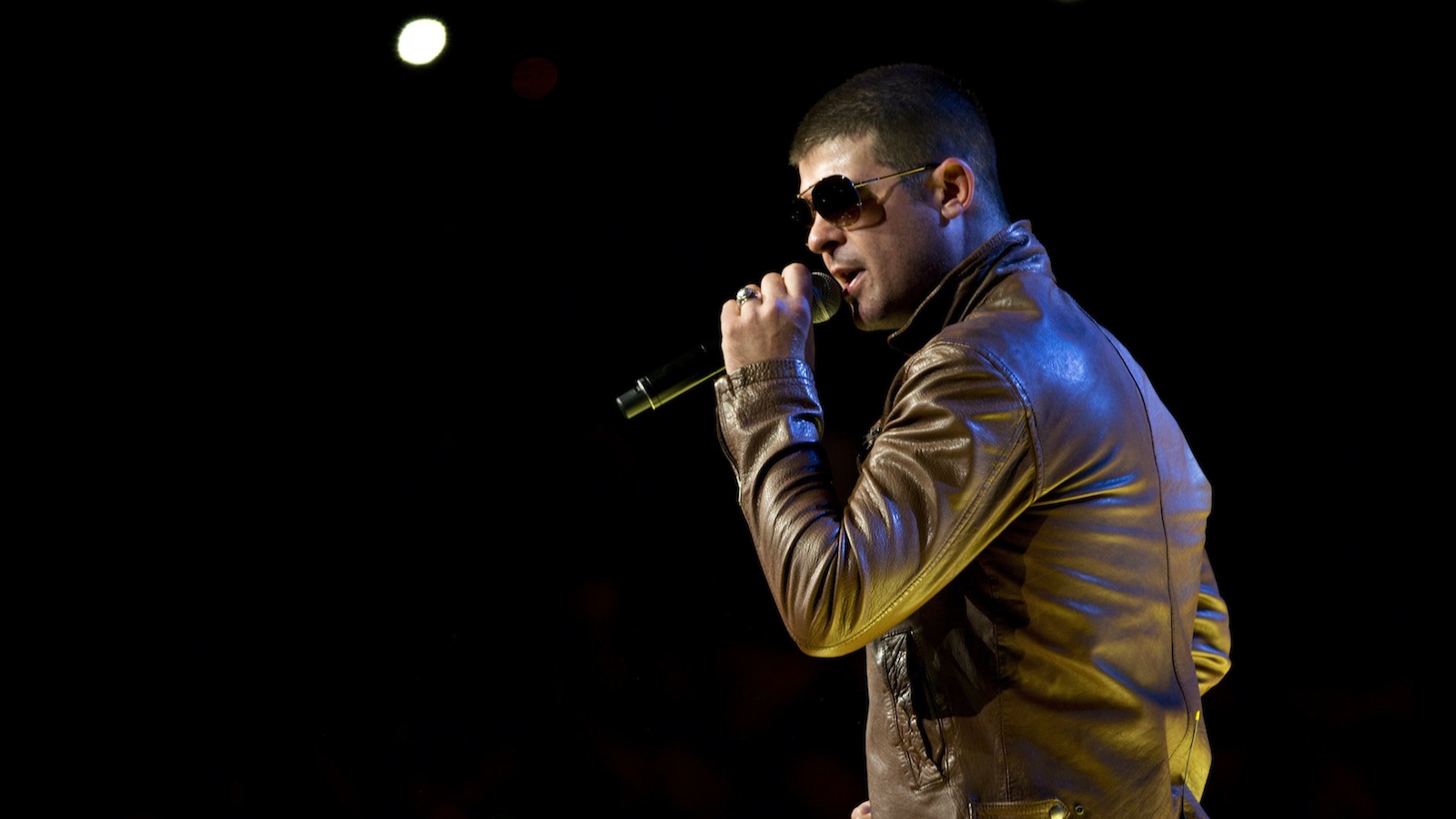

Robin Thicke. (Sarah Bentham/AP)

Share

Mawkish, thy name is Robin Thicke. There’s nothing blurred about his lines these days: The dual U.S.-Canadian singer who owned the song of last summer is dead-set on reuniting with his wife, Paula Patton—estranged since alleged infidelities in February—and is using every tool in his toolkit to do so. His new album comes out Thursday, and it’s not-so-subtly named Paula. Its tracklist includes titles like Get Her Back and Love Can Grow Back. Last weekend at the BET Awards, he made waves—uncomfortable, queasy waves—by appearing to sniffle and tear up during the debut performance of his song Forever Love off the new record.

Okay, so Thicke isn’t known for his subtlety anyway. This is the guy, after all, who raised hackles for a song whose lyrics veered a little too close to endorsing rape; in the music video, he doubled down by exulting around topless women as balloon letters exclaimed about Thicke’s phallic gifts. Paula‘s very first lyrics are unapologetically ham-fisted (“Baby I got a feeling / We ain’t never gonna be friends / Baby I got a feeling / Tonight”); the rest of it occasionally ventures into buffoonery (“Shine your rainbow of hope and hot pot of gold on my body” is an actual lyric). But for all the insipid music that Thicke has wrought here, it’s worth applauding him for doing one fairly remarkable thing: He’s snapped the long, spellbinding thrall in which breakup albums have held listeners around the world.

Take Coldplay’s latest record, Ghost Stories. There may not be a band quite as reviled as Coldplay, that most milquetoast of musical groups. On its surface, the album is full of hollow sentiments (“And I can’t get over / Can’t get over you / Still I call it magic / You’re such a precious jewel”) that, by any rights, should get a critical thrashing. But Ghost Stories comes hot off the heels of lead singer Chris Martin and actress Gwyneth Paltrow’s “conscious uncoupling,” so some now call it one of the best albums the band ever ever made. It’s earned grudging positive reviews, earning approving adjectives like “moody,” “emotional” and “vulnerable.” Never mind the fact that the album was recorded over the course of two years, and that the Martin-Paltrow split happened just two months before pressed albums found its way to shelves—such is the breakup album’s power.

Great music has come from despair, to be sure. Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear, a searing, exquisite record, is the most seminal; divorce court ordered him to send half the profits from it to his ex, Anna Gordy Gaye (the sister of his label’s founder, no less). And, for many mid-career artists, the breakup album is a useful, if unwelcome, tool in the toolkit: It can reawaken the creative spirit and inject a bit of relevance. Frank Sinatra resurrected his career with In the Wee Small Hours, which reflected his loneliness in his marriage to Ava Gardner. Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors is famously turbulent, a remarkable piece of art squeezed from the stones of three different marriages in freefall. Amy Winehouse’s finest (and last) record, Back to Black, was the product of a stormy relationship with her on-and-off boyfriend. The rapper Nas‘s most successful record since his classic debut was Life Is Good, which tackles his divorce head-on (the album cover features him, nonplussed, seated with a wedding dress on his lap). Bon Iver, Adele, Taylor Swift, Justin Timberlake, Maroon 5: All owe their rise to stardom, in at least some way, to the affecting release of a heart-wrenching record.

The best breakup songs catalyze sorrows into melody. They refract the singer’s experience into something universal, or flip a cliché into a fresh thought. (Canadian singer-songwriter Bahamas’s solemn koan in the excellent breakup record Barchords comes immediately to mind: “Overjoyed/There’s joy in feeling sad”.) There can be exquisite pleasure in music that makes you feel more of what you already feel.

But, increasingly, “great music comes from despair” has become a mantra rather than an interpretive possibility. The success of Coldplay’s latest record shows us we’ve started to conflate heartache with straight-ahead quality, eschewing the critical eye. If we’re getting a voyeuristic peek into heartbreak, it’s got to be good—even if the lines are as clichéd as “I’m wide awake / And now it’s clear to me / That everything you see / Ain’t always what it seems” (Katy Perry) or feature as horrible a simile as ” ‘Cause I took a chance on love / It’s like I’m dyin’ ” (Usher).

As for Thicke? He’s doing it all wrong. The album may be named Paula, but it’s all about him, right down to the blood on his face in Get Her Back and the sentiment of Freedom (“She can do whatever she wants,” he says, genuinely believing himself to be gracious). It’s the equivalent of emotional hostage-taking. It’s also surprisingly impersonal. As BET Awards host Chris Rock awkwardly joked after Thicke’s Sunday performance: “He’s singing like she don’t know him.” Thicke should know that this kind of thing doesn’t generally have the intended effect: Lenny Kravitz’s sunny Motown-stained ballad It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over is perhaps the finest in the field of modern grand-gesture torch songs, and his marriage to Lisa Bonet permanently dissolved anyway.

It was going to take a catastrophically ill-advised and painful album for us to fall out of love with the breakup album. By all early accounts, Paula is that record. For this, we should thank Robin Thicke.