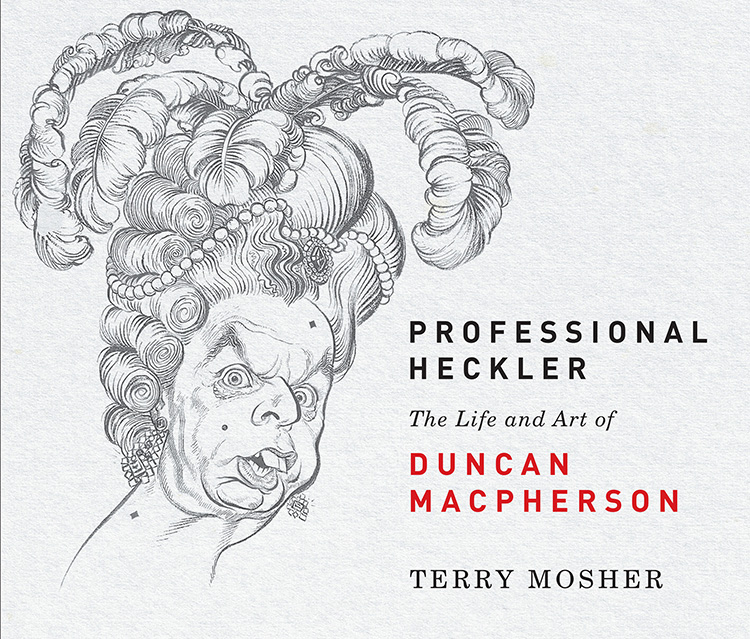

The man who drew Canadian politics

In a new biography Terry Mosher writes about one of this country’s most important political cartoonist, Duncan Macpherson

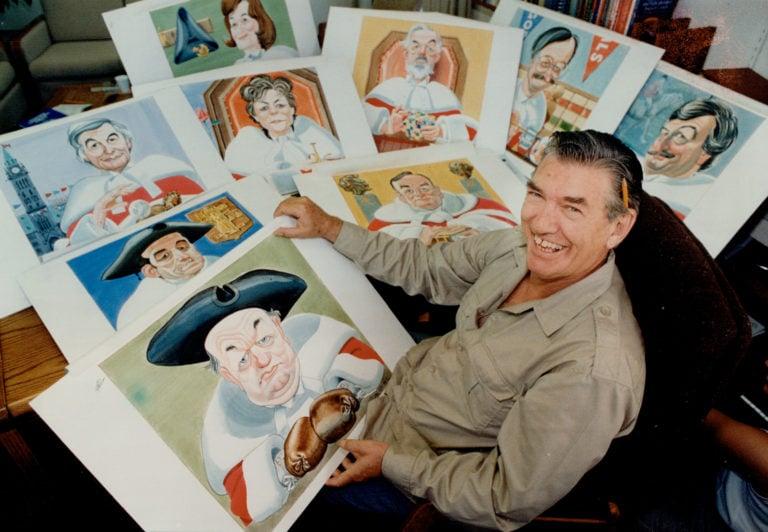

Cartoonist Duncan MacPherson (Doug Griffin/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

“Lots of people knew Duncan Macpherson, so what qualifies me to write a book about him, other than the fact that I admired him and am still standing?” asks Terry Mosher, in his new biography of the artist. “Well, no one else seems to be doing it.” Macpherson, who was arguably Canada’s most important political cartoonist, was also a mentor to Mosher (the well-known political cartoonist who goes by Aislin). “I consider this work to be a bit of payback for the great professional advice he gave me back in the 1970s when we became friends,” he says. In this excerpt from ‘Professional Heckler: The Life and Art of Duncan Macpherson’, Mosher looks at Macpherson’s years at Maclean’s in the 1950s, where he worked before joining the Toronto Star.

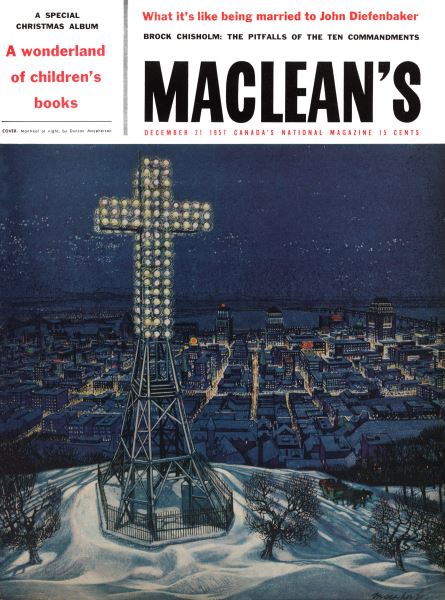

By the mid-1950s, Duncan Macpherson had started doing a lot of work for Maclean’s magazine, illustrating fiction pieces, and painting the occasional cover, as he did for the 1957 Christmas issue. The magazine had wanted to feature a star-filled view of Montreal from the vantage point of the cross atop Mount Royal, with the glowing city lying below in the background.

In a world before Google, illustrators had to do a lot of actual legwork to research their subjects. Macpherson rarely worked from photographs, preferring to prepare rough sketches on site for use as source material back in the studio. For this Maclean’s job, Macpherson took the train from Toronto to Montreal. He then walked up Mount Royal with the idea that this would give him the best bird’s-eye view of the city. Spotting the CBC/Radio-Canada transmission tower, Montreal’s highest structure, he thought he might as well climb it. He had got a very little distance in his climb before acknowledging it was a dangerous idea, so he abandoned the attempt. Macpherson then walked back down Mount Royal to reconnoiter, and soon decided the top of the new Montreal General Hospital would suit. He was fortunate to find an access point to the roof, and a convenient spot among the vents to sketch a series of cityscapes. During the overnight train ride back to Toronto, he assembled those sketches into a rough layout, and the next morning, returned to his studio to paint the final illustration. When he arrived at Maclean’s with the canvas, the paint was still wet.

As always, Macpherson had delivered: on brief and on time.

In his journal, he explained that, “… the Montreal Standard had paid very well in comparison to Maclean’s. However, Maclean’s was coming on like gangbusters with a first rate lineup of authors: Robert Thomas Allen, W.O. Mitchell, McKenzie Porter, Blair Fraser, Sid Katz, June Callwood and others. Another early and regular feature was “Jasper”, a panel cartoon by Simpkins. If ever there was an all-Canadian panel cartoon, that was it.”

Macpherson had actually preferred working for the Standard, because he had more freedom there, and the atmosphere felt a loss less buttoned-up than in Toronto. Still, working for Maclean’s suited him very well. At the corner of Dundas Street and University Avenue, it was close to home—not a train-ride away in Montreal—and the magazine had two great art directors in Gene Aliman and his assistant, Des English.

Christina McCall was a great Canadian journalist, who, with her husband Stephen Clarkson, wrote a much-lauded biography of Pierre Trudeau (Trudeau and Our Times). In an introduction to Macpherson’s 1978 collection of cartoons, she recalled an enlightening conversation with Duncan when she was a 22-year-old researcher at Maclean’s. “I was just out of university—earnest, ambitious and in awe of managing editor, Pierre Berton.”

“Berton wanted to write a feature on cartooning, and asked me to do some background research for the piece. I spent hours in the library, analyzing the great caricaturists of the past, and then persuaded Duncan Macpherson, a contributor to Maclean’s at the time, to talk to me about his work. I spun out torturous theories about the social import of Daumier and Hogarth, David Low and Herblock. Seriously uncomfortable with all this, Duncan would answer my ponderous questions with a “yep”, a “nope” or a “maybe.” Then he looked into my serious, eager young face and said: “What the hell, kid, what you’ve got to understand is that cartooning is a living.”

“We both started to laugh uproariously.”

Maclean’s superb editor in those days was former war correspondent Ralph Allen, originally from Oxbow, Sask. One of his most successful initiatives was a new feature at the magazine: writer Robert Thomas Allen’s funny short stories about life with his wife and two daughters.

Although he is almost forgotten now, Allen (1911-1990) was as popular a humorist in the 1950s, 60s and 70s as Stephen Leacock had been in his day. Allen played an important role in the evolution of Duncan Macpherson’s career.

Allen was born and raised “on the Danforth” in Toronto, so close to the Don River that he and his pals spent the hot summer days swimming there. Later, Duncan Macpherson was to produce a magical vision of those boys—not a swimsuit among them—horsing about in the water, choking on illicit cigarettes, or leaping off an overhanging willow branch into the river. It became the popular cover for Allen’s 1977 book, published by Doug Gibson, “My Childhood And Yours: Happy Memories Of Growing Up”.

After finishing school, young Bob Allen was glad to get work in the consumer catalogue business, where Macpherson also put in some time. These mail order catalogues were essential reading in Canadian homes across the country, and later, in the nation’s paper-starved out-houses. With no further education—because money was always tight—Allen tried his hand at writing, and began to submit humorous articles about everyday life to various magazines and newspapers. They were published, and actually brought in money. His popularity made him a sought-after contributor to major popular magazines like Reader’s Digest, The Imperial Oil Review, The Canadian–and, of course, Maclean’s.

Bob Allen was a short, shyly smiling man, who was always dressed in a suit and tie, with glasses perched on his nose –a strikingly old-fashioned figure. Yet his way of working would resonate with today’s millennial sitting and working at their laptop in a Starbucks. Allen would spend his days wandering around downtown, pausing to do his day’s work in a cheap café, scribbling on a napkin or a scrap of paper. When asked why he worked this way, Allen just mumbled something about liking to be around ordinary people. The result, however, was far from ordinary. It won him the affection of millions of readers, and the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour in 1956 (The Grass Is Never Greener) and again in 1970 (Children, Wives, And Other Wildlife).

Maclean’s editor Ralph Allen hired Duncan Macpherson to be Bob Allen’s illustrator. It was a match made in heaven. As for Duncan, he was delighted to illustrate these articles, as he considered Allen to be one of the best humour writers in North America.

Allen’s stories most often centred on life at home with his wife and two daughters. Macpherson enjoyed the tales, and provided affectionate cartoons of the four family members. However, the caricature of Allen morphed over time into a separate new character, a rumpled, bespectacled “John Q. Public”, who was later regularly featured in Macpherson’s work for the Toronto Star. American writer and critic Edmund Wilson, writing in The New Yorker, expressed his appreciation for Macpherson’s undersized common man, someone he said was “…gopher-nosed and chinless — surrounded by predatory monsters who bewildered him, bullied him and left him in tatters.”

Allen wasn’t thrilled about being identified with these ‘little guy’ portrayals, particularly when he and Duncan both ended up at the Toronto Star. Despite these minor frictions, Macpherson was always grateful for the association. “Thinking back, illustrating Robert Thomas Allen’s stories was the highlight of my association with Maclean’s.”

Macpherson also enjoyed his role in another of Ralph Allen’s projects for Maclean’s, which was to reacquaint Canadians with their history. Allen started by commissioning articles covering different eras. Macpherson recalls: “The period I covered mostly was early Montreal and Quebec. I found that I enjoyed the process of meticulously researching the time period before beginning the drawings.”

Maclean’s was starting to devote more space to news events, so Ralph Allen created a new feature called Up Front: two yellow pages at the front of the magazine to highlight breaking news. These were the last pages printed, so the work had to be done quickly. Within a couple of hours, Macpherson would spot-illustrate the section with thumbnail sketches. “The section grew, and two other illustrators came on board: Lew Parker and Bert Grassick. The three of us specialized in fast art, all being brush men.”

Duncan Macpherson was an excellent illustrator, of course, but there were many who were better known. It was his cartooning—not his illustrations or paintings–that was about to put him into the ‘genius’ category.

The charmed period for artists like Macpherson was about to end. Hand-rendered illustration was becoming passé. According to Duncan, “Quite simply, photography was faster, cheaper and not as much of a headache in terms of color separation.”

During World War II, Maclean’s covers generally alternated between photographs of war scenes and photos of pretty girls. After the war, the magazine turned to illustrators to provide cover art. Much as The Saturday Evening Post was showcasing American art and artists, Maclean’s featured paintings of interesting Canadian scenes. Taken as a collection, these images provide an invaluable reflection of Canada during the 1940s and 1950s.

In those days, photographs were rarely used as cover art. Maclean’s first issue of 1961 was a turning point. From that edition on, the magazine’s covers were almost exclusively photographs and montages. During the next dozen years, cartoons were featured only twice. In 1963, Duncan Macpherson drew a futuristic cover and foldout relating to the upcoming World’s Fair in Montreal (later called Expo67). Almost a decade later, during the Canada-Russia hockey series, Maclean’s put my cartoon of Phil Esposito on the front cover.

The 1950s really were a magic age for magazine illustrators. Maybe the sun always seems brightest just before it sets.