The man who fell to Earth: The ultimate David Bowie playlist

David Bowie shaped generations of music fans, and the music we’re still discovering today. Here are Bowie’s 20 most important songs, and why they matter

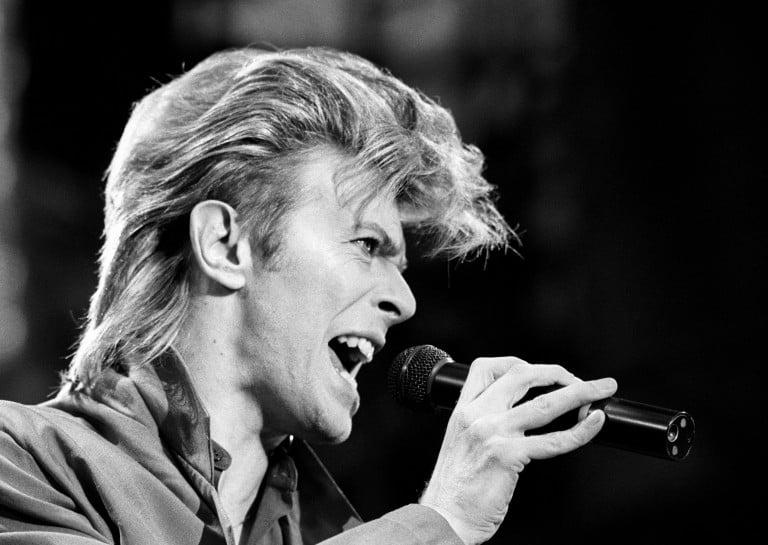

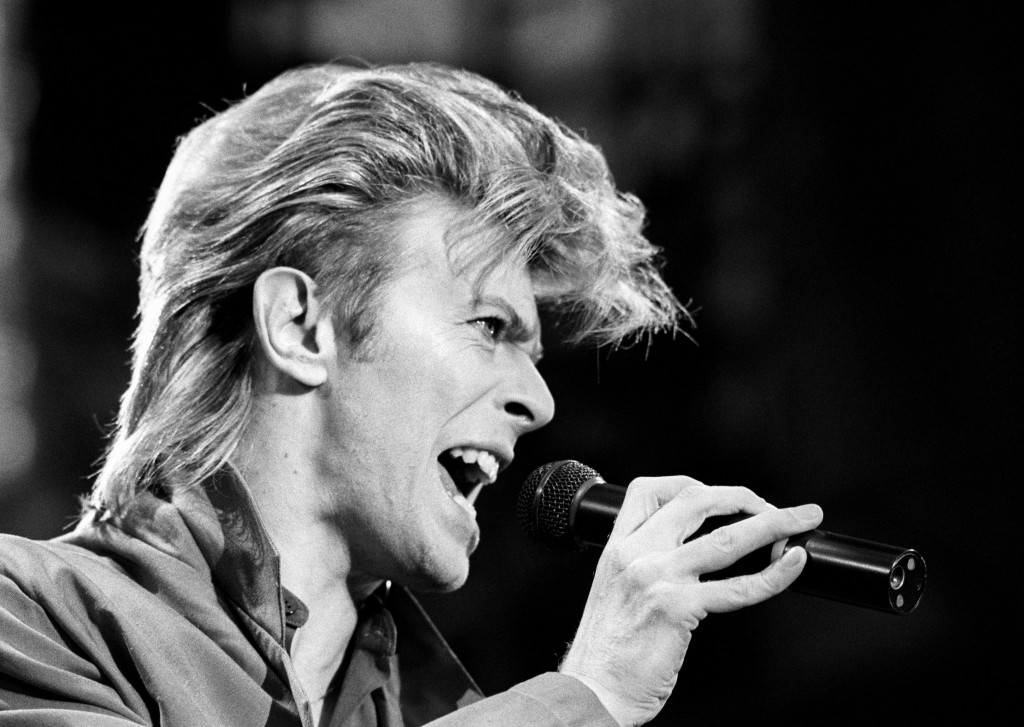

This is a June 19, 1987 file photo of David Bowie. Bowie, the other-worldly musician who broke pop and rock boundaries with his creative musicianship, nonconformity, striking visuals and a genre-bending persona he christened Ziggy Stardust, died of cancer Sunday Jan. 10, 2016. (PA, File via AP)

Share

It was Neil Young who put out an album called Trans, in 1982. But if any artist owns that prefix, it’s David Bowie: transgressive, transgender, translator, transformative, trans-generational. But what did we really know about David Bowie?

When it comes to the last 12 years of his life, the answer would be: absolutely nothing. After an emergency angioplasty forced him to cancel the remainder of his 2004 tour, Bowie loomed as large in our imagination as he always had. Not because the public was eagerly awaiting new work: Albums from the 1990s and 2000s—Reality, Heathen, Hours, Earthling and Outside—appealed to hardcore fans only, with only one single (“I’m Afraid of Americans”) leaving any dent in the world outside Britain.

Related: David Bowie, dead at 69

But because the first 20 years of Bowie’s career continually rewrote the rules of rock music, constantly borrowing from underground trends of the day and bending them to his own vision, he was always on our mind. Bowie was not an innovator, as an examination of his obvious influences makes clear; he hung around and borrowed extensively from Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, Iggy Pop, Luther Vandross, Klaus Nomi, Brian Eno, Nile Rodgers, and Trent Reznor—to name just a few he absorbed into his oeuvre. But in terms of repackaging radical ideas and using his platform as a pop star to reach far and wide, he set the agenda for decades of rock, pop and avant-garde music, influencing everyone from Madonna to Kanye West to Arcade Fire to Antony and the Johnsons.

Ask any small-town outcast or art school student who grew up in the 1970s or 1980s who their pop idol was, and the near-unanimous answer will be: David Bowie. Bowie, who explored gender fluidity in ways society still has trouble processing 50 years later. Bowie the shapeshifter, whose 90-degree turns were essential for artistic growth, who proved time and time again that it was never too late—or impossible—to reinvent yourself. Bowie the alien, the cypher, the man whose elegance and natural otherness set him apart in every situation, on- or off-stage, on screens large and small. Bowie, who sang with both Bing Crosby and Iggy Pop, who clowned around with Mick Jagger and worshipped the weirdest singer-songwriter of the late 20th century, Scott Walker. Bowie the actor, whose choice of characters reveals so much: Pontius Pilate, Andy Warhol, Nikola Tesla, a goblin king, a vampire, a space alien. Bowie the cultural barometer, who was more than happy to share with you his reference points and celebrate truly alternative culture. Did you ever feel that you never fit into this world, but had the capability to change it and bend it? David Bowie was your man—if, in fact, you considered him to be human at all.

Because his legacy was always being rediscovered by new generations, the fact he had been silent for more than a decade didn’t seem that strange. Most fans had forgotten about his health issues; many assumed he wasn’t putting out music because he simply didn’t have anything else to prove—not untrue, of course. No one outside his family or closest confidantes knew about the cancer he fought for the last 18 months of his life.

His comeback album, 2013’s The Next Day, was a surprise release, the creation of which was a closely guarded secret. 2016’s Blackstar, released just last Friday, on Bowie’s 69th birthday, was another surprise, preceded by the 10-minute long title track in December. The jazz-tinged album has received unanimous praise as his best album in—what, 30 years? More? It’s a beautiful, daring work and, given the timing, a haunting experience. Which was his plan all along, according to his producer, Tony Visconti, right down to the video and lyrics for “Lazarus”: “Look up here, I’m in heaven / I’ve got scars that can’t be seen / I’ve got drama that can’t be stolen / Everybody knows me now.”

Do we, though? Did we ever?

The songs that shaped Bowie’s career

“Space Oddity,” from David Bowie (1969). Released five days before the Apollo 11 moon landing, the song by the then-unknown artist was somehow landed by Bowie’s management in the BBC’s coverage of the event. Which is even more strange, considering that the song’s ending clearly implies that Major Tom loses touch with ground control and is left floating in space.

Title track from The Man Who Sold the World (1970). Look at that album cover, and eat your heart out, Boy George. The title song would be covered 24 years later by Kurt Cobain, who was known to wear dresses in public to bait homophobes, and had his own hangups about selling out to the world.

“Changes,” from Hunky Dory (1971). “Turn and face the strange” might well be a rallying cry for Bowie fans of all generations. This week, however, the key line might well be: “Look out all you rock’n’rollers / Pretty soon now you’re going to get a little older.”

“Five Years,” from Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders of Mars (1972). Bowie opens his greatest pure rock’n’roll album with a 6/8 epic poem with killer couplets like this one, that would make Bob Dylan jealous: “A soldier with a broken arm / fixed his stare to the wheels of a Cadillac / A cop knelt and kissed the feet of a priest / and a queer threw up at the sight of that.”

“See Emily Play,” from Pin-Ups (1973). Pink Floyd was just about to release Dark Side of the Moon, but Bowie wanted to pay tribute to its exiled founder, Syd Barrett, by reinventing this Barrett gem, which he did on Pin-Ups, his all-covers album. Bowie was always trying to shed light on contemporaries he admired, giving his pop audience a master class in the history of alternative art.

“Rebel Rebel,” from Diamond Dogs (1974). The anthem of androgyny needs no further introduction.

“Fame,” from Young Americans (1975). Jamming with John Lennon over a blatant James Brown groove: surely this must be yet another case of a white artist—one of the first white artists to appear on Soul Train, no less—stealing from a black icon? Yes, this sudden shift to soul music could be seen that way. But the funny story about “Fame” is that it’s much more complicated than that. His guitarist, Carlos Alomar, had played in—and was fired from—James Brown’s band. Bowie and his band played a cover of an obscure ’60s soul single called “Foot Stomping” by the Flares on the Dick Cavett show before recording Young Americans. James Brown saw the performance and immediately went into the studio to rip it off for a song called “Hot (I Need to Be Loved).” By the time “Foot Stomping” had transformed into “Fame,” Brown’s nearly identical record had already beaten Bowie to the charts, albeit much lower than where “Fame” would end up: At No. 1. Not surprisingly, however, you’ll only ever hear “Fame” on classic rock radio—not “Hot” nor anything else by James Brown.

“Wild is the Wind,” from Station to Station (1976). A Johnny Mathis song best known for a version by Nina Simone. Bowie sings it with an aching beauty—perhaps because this was a year of great turmoil for him, during which he fired his manager, overdosed on cocaine several times, and was making bizarre pro-fascist comments in the press.

“Warszawa,” from Low (1977). After bottoming out, Bowie went to Berlin with producer Brian Eno for a series of albums starting with Low, which was heavily influenced by German electronic music of the time, such as Kraftwerk, Neu and Harmonia—which is most evident in this instrumental track.

Title track from Heroes (1977). The only “hit” to come out of his Berlin period, it remains one of the most eerie and beautiful songs of his career, marrying Velvet Underground guitars with droning synths and one of his finest vocal performances.

“DJ,” from Lodger (1979). “I am a DJ / I am what I play.” This came out at the height of disco, although it was far too druggy and deranged to actually be a dance hit; it owed more to Talking Heads and Public Image Limited, if anything at all.

“Ashes to Ashes,” from Scary Monsters and Super Creeps (1980). The hit single from the last album most Bowie fans agree to be his best; it’s also the last time he “faced the strange” for about 15 years.

“Under Pressure,” from Queen’s Hot Space (1981). A vocal showdown with Freddie Mercury, it’s not at all an understatement to suggest that this is the greatest duet ever recorded between two male vocalists.

Title track from Let’s Dance (1983). Whoa, where’d the weirdo go? There was no longer any black-and-white, or shades of grey, just a Technicolor ’80s pop daydream produced by Nile Rodgers of Chic (and who would soon produce the breakthrough by that other great shapeshifter, Madonna). This is a fantastic pop single from top to bottom, from the “Twist and Shout” opening to the Creature Cantina horn section to the big-’80s drum sound to the percussion bouncing around a giant reverb chamber to the Stevie Ray Vaughan guitar extro. Oh, and perhaps Bowie’s most powerful vocal performance for sheer technique alone, displaying every bit of his range.

Title track from Tonight (1985). Yes, the reggae duet with Tina Turner. By this point, we’d come to expect just about anything from Bowie, and this is one of his most underrated pop moments—and of course unlikely to be praised by anyone whose lives were changed by Bowie in the ’70s.

“Day In Day Out,” from Never Let Me Down (1987). This song will make no one else’s playlist of David Bowie greats for one obvious reason: it’s terrible, a crime against music. It’s presented here if only to demonstrate the depths Bowie—and, to be fair, so many ’60s and ’70s icons in general—had sunk by 1987. If it’s any consolation, Bowie himself later called Never Let Me Down “an awful album.”

“Under the God,” from Tin Machine (1989). Before the ’80s were done, Bowie stripped down to basics and formed this (apparently democratic) rock band, inspired by the Pixies and predating the grunge explosion by two years. Largely mocked at the time, it holds up better than you probably remember.

“I’m Afraid of Americans,” from Earthling (1997). Bowie was listening to Nine Inch Nails and London’s drum’n’bass scene and thought he would chime in. Whatever, old man. But against all expectations—especially considering his discography of the preceding decade—the result was a surprising renaissance.

“The Loneliest Guy,” from Reality (2003). “I’m the luckiest guy, not the loneliest guy,” he sings here, but he sure sounds like the last man on the planet on this devastatingly gorgeous vocal.

“Lazarus,” from Blackstar (2016). Even if this wasn’t from the last album by a great artist, even if it wasn’t accompanied by a creepy video about death that debuted mere days before his passing, it would still be one of Bowie’s greatest singles: the weeping guitar riff, the moaning saxophone, the stately rhythm section, and a vocal performance rich with experience, faded glory, dignity and resilience. So few artists continue to make career-best work so late in life; for a while there, it looked like Bowie would not be one of them. As it turns out, he orchestrated his high-point finale in ways even his biggest fans couldn’t have predicted, and left us loving him even more.