The Building: Labrador’s striking new cultural centre

For the Nain project, Newfoundland-born architect Todd Saunders took inspiration from Inuit sod house shelters on nearby Rose Island

(Photographs courtesy of Saunders Architecture)

Share

The town of Nain, on the rugged, mountainous Labrador coast, gives new meaning to the word “remote”: it’s inaccessible by road and overlooks the wild Labrador Sea, which freezes for six months of the year. It’s also a gateway to the jaw-dropping Torngat Mountains National Park and an important cultural centre for Labrador’s Inuit community, who make up the vast majority of the area’s population. (Nain was founded in the late 1700s by Moravian missionaries.) Until recently, the community had nowhere to showcase artifacts from its rich history. That’s why, in 2009, the self-governing Nunatsiavut government commissioned Newfoundland-born, Norway-based architect Todd Saunders to design the $19-million Illusuak Cultural Centre.

Saunders is known for creating contemporary geometric structures that draw from the striking landscapes that surround them. He’s also the architect behind Newfoundland’s Fogo Island Inn, a celeb-magnet destination hotel meant to evoke the stilted fishing structures built by outport settlers 400 years ago.

For the Nain project, Saunders took inspiration from nearby Rose Island, specifically its sod houses—rounded, sunken temporary shelters the Inuit would build in the summer months. The result: a curved, flowing structure that features a café, a craft shop, studio space and a 75-seat theatre, as well as offices for the Nunatsiavut government and Parks Canada. The building opened in the fall of 2019 and now serves as a gathering spot for the community to celebrate its roots. So far, it has hosted grade school visits, presentations, meetings, cultural performances and weddings.

Illusuak was built on solid permafrost in one of the country’s harshest, most isolated environments. Its building materials had to be floated in by barge. The steel-and-timber-frame structure is wrapped in ceiling-height windows and hand-cut Kebony spruce cladding, which will weather to grey with time, blending into Nain’s landscape. Inside, there’s timber panelling, stone floors and locally sourced sealskin floor coverings. Among the treasures housed in Illusuak’s exhibit space are Inuit-made soapstone pots and lamps and whalebone and ivory tools, some of which were returned home from the Smithsonian.

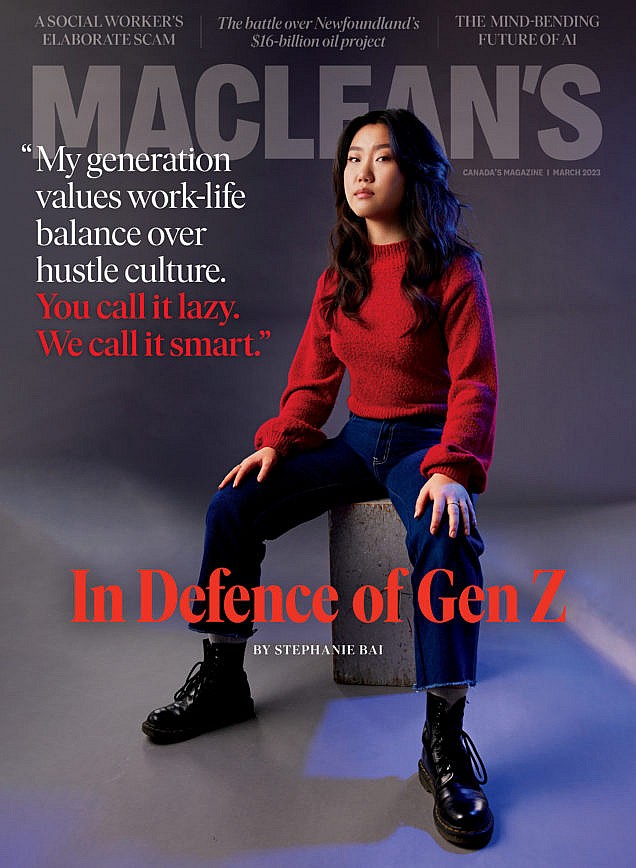

This article appears in print in the March 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $29.99.