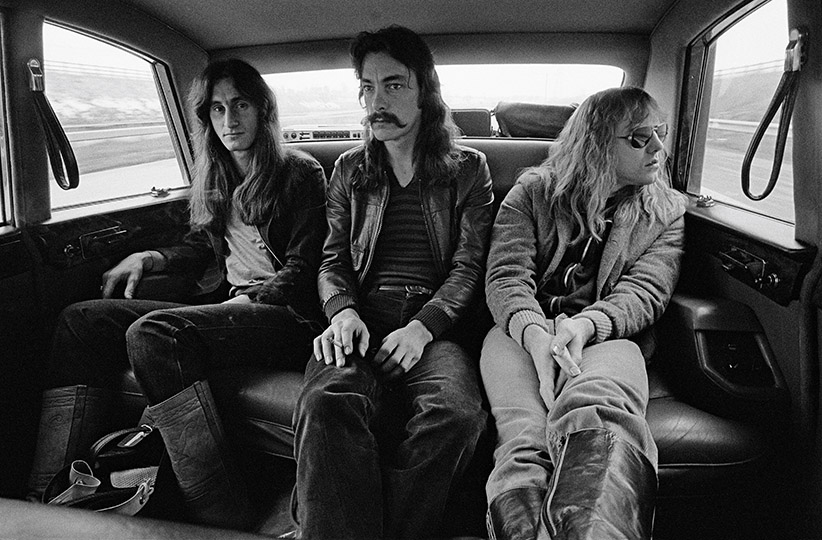

What a Rush! How an unhip trio became superstars

It’s 2015, and yet the ‘terminally unhip’ Rush is one of the world’s biggest touring bands

Geddy Lee performs on stage during Rush’s R40 Tour in Austin, Texas. (Randy Johnson)

Share

During the first set of Rush’s R40 tour, Alex Lifeson’s guitar amps are bedecked by plastic lizards—stegosauruses, triceratopses and T-Rexes, too. Lifeson, singer-bassist Geddy Lee and drummer Neil Peart have been cracking dinosaur jokes for so long now that the props are part of R40’s nostalgia-laden concept. Their setlists run chronologically backward through their songs and staging, from the ornate steampunk aesthetic of Clockwork Angels to a recreated high school gym for Working Man. It’s a cheeky reminder of less heady times.

That a grandfatherly power trio branded “terminally unhip,” and consistently rejected by mainstream radio, should be selling out arenas across North America—in under an hour in major markets—approaches the unreal. Just how it happened is hard to pin down. Rush’s appearance as the bemused idols of worshipping fans in the bromance comedy I Love You, Man (2009) portended a new celebrity. Says Lifeson, “Before, it was just, ‘Hey, nice to meet you. Like your stuff.’ Now there’s a nervousness when we get recognized. Being Canadian, I want to apologize: ‘Oh, I’m sorry you’ve enjoyed it so much.’ ” The 2010 documentary Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage showed the band as family men and it tripled their female audience, according to long-time manager Ray Danniels. “The icing on the cake,” he says, was Rush’s 2013 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

But none of this quite explains their appeal in 2015. The clues are in their tour, which Jillian Maryonovich, creative director of the band’s annual fan convention, RushCon, calls “a moving museum of Rush”: 40 years of unfashionable music and theatrics that somehow tap into the current moment. In an era obsessed with authenticity and artisanal everything, they are an antiviral phenom, a craft band, the unvarnished Real Deal.

In 2006, at the start of what Danniels views as Rush’s 10-year ascension into mainstream celebrity, British sociologist Richard Sennett presaged the “handmade” movement with The Culture of the New Capitalism. He sketched a working world where the consultant, who swoops in to solve problems, is more valued than the craftsperson. He decried mass-produced goods, whose sellers magnify “minor differences quickly and easily engineered” and argued one could “revolt against this enfeebled culture” with craftsmanship, i.e., “the desire to do something well for its own sake.”

Rush’s career embodies this idea. Peart told writer Martin Popoff in the 2004 biography Contents Under Pressure that he believes in “creating a masterpiece in the true sense, the way it used to be, in the days of the apprentices. If you wanted to be accepted as a master in the guild . . . whether you’re a stonemason or a guilder or carver or whatever . . . your work was necessarily, within the craft, an attempt to achieve that mastery.” For all of their futuristic imagery, Peart and his comrades have always hewed to the old virtues of work.

Their 1974 breakthrough song was the joyously sludgy Working Man, both a celebration of blue-collar workers and a critique of the monotonous 9-to-5 week that Rush sought to escape. “It seems to me I could live my life / A lot better than I think I am,” Lee wails. The ideal is to work for oneself, to cast off the drudgery of the factory: “Life in two dimensions is a mass production scheme,” Lee sings on 1985’s Grand Design.

They would hone their skills on tour—playing up to 140 shows a year in their early days— and in the studio. “Right from Day 1, we wanted to be the best players we could be,” says Lifeson. “Maybe that was a nerdy approach, but it’s done well for us.” In 1978, after punk broke, they were holed up in a cabin in Wales for four months, devising such challenging pieces for the album Hemispheres that they then had to figure out how to play them live: “It seemed unbearable at times. We had to go through difficult steps to find out where the easy ones were. You want to shoot yourself at some point, but when you get through it, it’s a great sense of accomplishment.” Even in the 1980s, when they wrote shorter, synth-driven songs, says Lifeson, “We’ve never simplified what we’re doing; it’s even more difficult to squish everything into four minutes.”

Their modus operandi couldn’t be further from the contemporary ideal of sharing music on social media, getting the right people to promote it, and exploiting it for 15 minutes of fame. Chris McDonald, professor of ethnomusicology at Cape Breton University and author of Rush, Rock Music and the Middle Class, describes the band paying its dues “to reach a certain level of enlightenment. As one acquires skills, one acquires experience; one acquires virtue, and that’s something fans see in Rush’s career—starting as this bar band and releasing your album independently; getting a break, and still having to slowly build up.”

Apart from a dubious period in the 1970s when they wore robes—which they aren’t resurrecting for this tour (“I can’t fit into my kimono quite like I did then; I look more like a sumo wrestler,” Lifeson laments)—Rush have always projected the anti-image “image” of regular guys. “They found fans that were like them,” says McDonald. “Young musicians looked up to them as exemplars, and that became such an important part of their appeal.”

And in contrast to the hit-factory pop model of technology-focused songs devised by committees of producers, Rush craft their music with no thought to glittering prizes. When they were at a low commercial ebb in 1975, Danniels placated their U.S. label by promising radio-friendly singles; instead, Rush delivered the defiantly complex 2112, with its side-long, titular sci-fi epic. It was a statement of artistic independence that also expressed their disdain for the bean counters—Danniels says, “Most of the people at that label wouldn’t have known the difference between Dark Side of the Moon and a [record that would] stiff.”

It has always been the three of them against the world, playing every instrument they could reasonably be expected to play onstage. Popoff notes, “Geddy plays bass; he plays bass pedals with his feet; he reaches over and plays keyboard patterns. And anything else that they needed in a live setting, they triggered—there’s no super-faking going on with those guys.” Says Danniels, “You look at the Rolling Stones, and how many other guys onstage are there? Fleetwood Mac [has] other people behind the stage playing, but these guys are doing a three-hour set—they’re like athletes.”

Kids discovering Rush’s music on YouTube can see the same guys live, playing the same material with brio. After all, intergenerational angst is passé—in 2013, MTV president Joe Friedman told Time that Millennials were “not rebelling against their parents at all, they’re moving in with them.” And when twentysomethings sport beards and dye their hair grey, eschewing the cult of youth, sexagenarians like Rush can have a unique cachet.

Lifeson says at some R40 shows, he has seen “a group of girls in the first couple of rows that look somewhere between 14 and 17, and they’ll sing every word to every song, including stuff from the first album.” Reviews from audiences and critics have been glowing, and fans are being treated to the unique spectacle of a late-career surge from a band of outsiders, with none of the drama of break-ups and reunions. And for the trio themselves, “it’s been amazing,” marvels Lifeson, “just unbelievable. Most important, we’re having a riot.”

Rush won’t be able to play like this forever, or even for very long. Peart is suffering from tendonitis—he has downsized his epic drum solos—and Lifeson has psoriatic arthritis. “I’m starting to feel it in my index finger and my thumb on my left hand, which is kind of critical,” he says, “so I get cortisone shots and try to keep it as loose as I can. I’ll be 62 soon, and it’s getting a little more challenging to stay on top of it.”

The band’s future, beyond the end of this tour in Los Angeles on Aug. 1, is a question mark: “We’ve talked quite openly about this possibly being the last major tour that we’re going to do,” says Lifeson. “There’s no point in going out and being the ghost of yourself just to make a few bucks.” What’s more, having sacrificed family time for Rush’s career, he plans to be around for his grandchildren: “I want to be the custodian of great experiences for them—that’s a pretty important job.”

Still, with Lee living five minutes away in Toronto, Lifeson is always tempted to write music; “I know Neil would be up for it too,” he says. And with Danniels “cautiously optimistic” about adding tour dates, Rush’s ever-expanding cult needn’t wish for time to stand still.

By the end of their R40 shows, Rush are playing Working Man with their amps hoisted on folding chairs—“just like in 1971,” says Lifeson. “There’s a joy in the house and onstage; we’re goofing around.” For RushCon’s Maryonovich, the effect is “charming and sweet. I sit and watch these guys play, as I have for the past 20 years, and think, ‘Wow, at one point, they were unsure they were going to be successful. They didn’t know that this was going to be their life.’ It almost got me choked up, thinking they were once in high school and wanted to be musicians.”

[mlp_gallery ID=747]