Before Game of Thrones there was—Bloom County?

An ’80s water-cooler staple, Berkeley Breathed’s daily comic strip now tries its luck in the Internet age

Berkeley Breathed/CP

Share

The biggest news in cartooning this month is something that hasn’t been big news for a long time: a daily comic strip. When Berkeley Breathed, creator of the satirical strip Bloom County, announced that he would revive the strip on his Facebook page, it got coverage in outlets like the Washington Post and NPR that wouldn’t normally cover your local newspaper comics page.

The original only ran from 1981 to 1989, but it’s still more famous, with a more ardent fan base, than any current daily comic. “I loved Bloom County,” says Noah Berlatsky, editor of the comics website The Hooded Utilitarian. “The strip was a glorious mix of invention and deflation.” It may be too early to tell if Breathed’s new instalments will live up to the original, but one thing he’s already proven is that the ’80s was the last era when people cared about comic strips.

Daily strips have long been mocked for being old-fashioned and appealing mostly to aging newspaper readers; the original Bloom County would often make fun of Nancy, Blondie, and other legacy strips that go on long after their creators die. But in the 1980s, a small group of young cartoonists made comic strips that were genuinely relevant. Bloom County was in that group, along with Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes and Gary Larson’s The Far Side. All of these strips ended early, because the creators burned out from the pressure of having to produce a strip every day. And not all of them were respected by their peers; though Bloom County won the Pulitzer prize, it was also denounced for imitating Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury (something Breathed freely admitted) and for, in the words of editorial cartoonist Pat Oliphant, “passing off shrill potty jokes and grade school sight gags as social commentary.” But even those who didn’t like these strips had to care about them: For a few years, people would discuss them every day the way they now discuss the latest instalment of Game of Thrones.

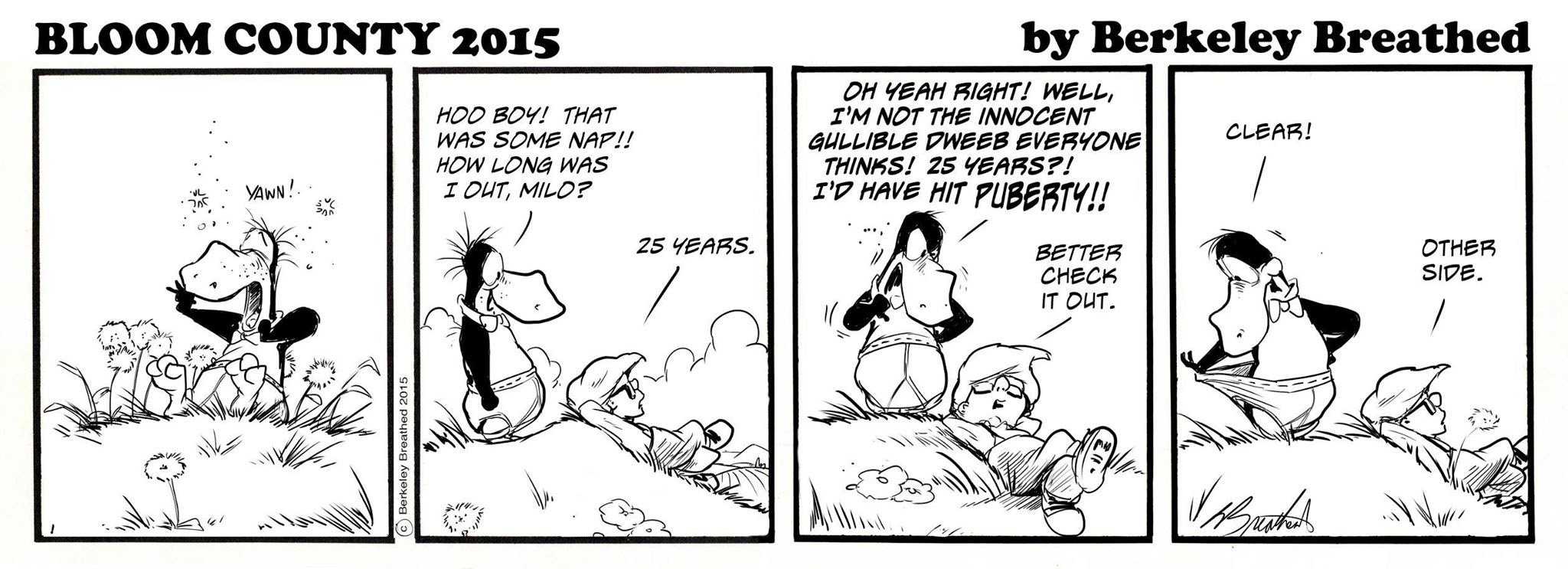

Bloom County used its cast of humans and talking animals—like Opus, a naive penguin, and Bill the Cat, a vicious parody of Garfield—to make fun of the Reagan administration, the rise of political correctness, and the slow death of print media. Breathed himself now seems to acknowledge that Bloom County is a relic of a time when comic strips mattered more. Even though he’s featured several of the characters in spinoff strips, the new series ignores all that, and acts as though they’ve been away since 1989. The premise of the first storyline is that Opus has been asleep since then, and has to adjust to things that have changed since those old days. “I’m not an ’80s relic!” he insists. But his appeal is that he is just that.

Why were the funnies, as they used to be called, so much more important in the ’80s than they are now? The reasons are obvious, Berlatsky says. “Newspapers had less competition and were more central to the culture. Big comic strips like Calvin and Hobbes or Bloom County or Doonesbury could reach much larger audiences than strips can generally reach now.” It also helps that the ’80s was also the last time comic strips were allowed to have an edge. In his notes for Idea and Design Works’s collection of Bloom County reprints, Breathed often comments that newspaper editors of the era let him get away with adult humour that would be banned today. Bloom County did a storyline about Bill the Cat’s affair with UN ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick, and another strip ended with the punchline, “He wouldn’t know a pink snow bunny if it walked up and bit him on the ass.” Today’s newspapers, whose audience is even older and more conservative than it used to be, won’t allow even the mildest controversy outside editorial cartoons.

People used to hope that the Internet, with its younger audience, could step into the breach. But though there are many comic strips online, few have the kind of broad, multi-generational audience that the ’80s strips attracted. Berlatsky says that Randall Munroe’s xkcd, where stick figures discuss math and computers (and which went viral with catchphrases such as “someone is wrong on the Internet”), has a big reach, “though that’s often through particular cartoons being shared individually, rather than through people looking at it every day.” On the Internet, cartoonists don’t have the pressure newspaper cartoonists had to produce every day, or to seek out a wide audience. Breathed told the Washington Post he’s not doing the new Bloom County for newspapers because “dead-tree media requires constancy and deadlines and guarantees.” But those things may have helped to make his strip popular.

Still, even if Facebook can’t make comic strips as relevant as they were in the ’80s, it’s a great place to deliver nostalgia. Free from the constraints of daily deadlines, Breathed can create a new gag whenever he wants. And ’80s nostalgia can sometimes become relevant again, anyway. The original Bloom County made a lot of Donald Trump jokes.