A bear. A five-year-old. Unthinkable terror.

A book review about the quest for survival after a bear attacks a family’s campsite

Share

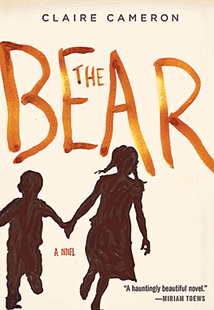

The Bear

By Claire Cameron

Any Canadian author who writes a novel set on an island in northern Ontario in which a bear plays a central role and then titles it The Bear is setting herself up for comparisons to Marian Engel’s classic novel Bear. To then make it a story of unthinkable trauma narrated by a five-year-old is also destined to invoke Emma Donoghue’s Room. Yet Claire Cameron’s story of two children cast adrift after a bear attacks their family’s campsite forges an original path. The result: a gripping, affecting story that reads like a hybrid of Henry James’s What Maisie Knew and Margaret Atwood’s Survival.

Anna Whyte is tucked into her sleeping bag next to her two-year-old brother, known as Stick, when the bear attacks. Hidden by their father in one of his last acts, Anna is left to protect them both. Her observations flow in ungrammatical stream-of-consciousness—concern for her doll, irritation with Stick, thinking about the Barbie dolls her mother will not let her have, faith that her parents will return. It’s a childish patois filled with Disney-informed chatter about princesses and magical fish—but tempered with adult cadences and wisdom. “I call Mommy and Daddy my throat feels like the deck of the cottage that gives me splinters in my foot,” she says, early on. Later in the book, the canoeing term “lily-dipping” is recast as “dipping for lilies.” The reader is left to connect the dots—conflict between Anna’s parents, the perils she can’t see, that the “big black dog” is not that at all, Anna’s inchoate need for her family—as well as narrative inconsistencies, such as Anna’s varying understanding of death.

The story was inspired by the tale of a couple killed by a bear in Algonquin Park, explains Cameron, a former camp counsellor in the area; she added the children, a literary masterstroke. She nails the details: movement inside a canoe, the texture of the wild. It isn’t a spoiler to say that the last section in Toronto after the children’s return is as harrowing as what went before. It serves as a reminder that the quest for survival doesn’t end with rescue—and that children are not alone in venturing into terrain far more treacherous than they can ever know.

Anne Kingston

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary.