A heartrending memoir from Jordin Tootoo

Its the most compelling, honest and unputdownable hockey read in years, says reviewer Nancy Macdonald

Share

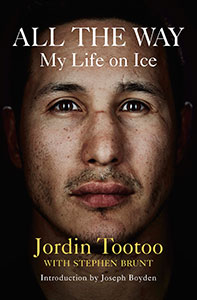

ALL THE WAY: MY LIFE ON ICE

Jordin Tootoo, with Stephen Brunt

Hockey biographies share a yawning predictability. With the obligatory backyard rinks and perky, middle-class families, they have the feel of a Tim Hortons commercial, with less insight. Then comes Jordin Tootoo’s book, the most compelling, honest and unputdownable hockey read in years. Written in a raw, minimalist style that echoes the Inuk star’s spare patter, the book, by Sportsnet’s Stephen Brunt, tells the story of his alcohol-soaked upbringing, of rehab and redemption. In places, it’s so achingly sad, it’s hard to read on.

Tootoo, now with New Jersey after a 12-year stint with Nashville and Detroit, is unsparing, particularly when describing those closest to him: “When my father drinks, especially hard liquor, he becomes an evil monster—a [expletive] scary guy,” he writes of his beloved father, Barney, a respected elder in Nunavut’s Rankin Inlet.In outlining the depths of his own descent into alcoholism, he sheds light on the NHL’s profoundly secretive substance-abuse program. “I was still hung to the gills and I reeked of booze,” Tootoo says, recalling the day the Predators’ GM, David Poile, forced him into rehab: “I was thinking, ‘What the f–k did I do now?’ I had been so drunk, I’d blacked out.”

At first, Tootoo couldn’t recognize himself in his fellow patients at the Canyon, the famous Malibu treatment centre: “We were sitting in a circle and I was looking around and thinking, ‘Am I really like this?’ ” But he’s been sober ever since. Tootoo, a five-foot-nine enforcer, has, after all, made a career of defying odds. He grew up just outside the Arctic Circle, and didn’t play organized hockey until he was 14, yet, somehow, muscled his way into the NHL.

For a while, it seemed two Inuks were set to break through. Then, when Tootoo was 19, tragedy struck. His brother Terence, then 22 and playing in an NHL feeder league, committed suicide. The book’s title is a reference to a note he left Jordin, his best friend, imploring him to “go all the way.”

Ultimately, for Tootoo, returning home was just as important as making it out. Though he once saw Rankin as a black hole of booze, abuse and suicide, the book ends in his community, with his realization that home is also the source of his formidable strength. He returns often in dreams, Terence by his side. In one dream, the brothers become separated while walking together. Terence, looking back toward him, says: “Jordin, you can go your own way now.” It “feels like Terence is still somewhere out there,” Tootoo says, “like he ran away, but he’s still somewhere in this world.”