A return to Second World War England: Book review

Humphreys’ new novel tells a story that moves from a POW camp in Germany to the London area

Share

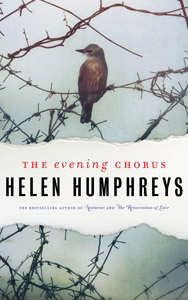

THE EVENING CHORUS

Helen Humphreys

In 2013, Humphreys released Nocturne, her moving memoir of her younger brother, who died of cancer at age 45. Martin Humphreys’ death, and the way his sister shaped and memorialized her response to it, suffuse her new novel, even as The Evening Chorus returns her to familiar territory. Much of the author’s earlier fiction was rooted in the wartime-Britain memories of her parents, who moved their family to Canada in 1961. And although she said after Coventry (2008) that she was “done with England” and the Second World War, having “worked out whatever it is I was working out,” Humphreys is right back there in a story that moves from a POW camp in Germany to Ashdown Forest, only 60 km away from London, during the Blitz. There is more, it would seem, to be worked out.

Three main characters, as subtly limned as any of Humphreys’ past creations, all find solace in nature as the world falls apart around them. There’s RAF officer James Hunter, a tribute to the extraordinary real-life John Buxton, who wrote a pioneering ornithological book during his POW stay. James begins to study a pair of redstarts nesting just outside his camp; his dedication to the task enables him to note parallels in the lives of birds and men—food, for POWs and redstarts, is the constant preoccupation—and to cope with the camp’s capriciousness, which runs from sudden murderous brutality to the kindness of the Kommandant, a fellow birder who takes James on an excursion to see some rare specimens. There’s Rose, James’s wife of only six months, who is almost subsumed by nature in her cottage at Ashdown, and Enid, James’s sister, who comes to stay with Rose after losing her London flat, job and married lover in a single bombing attack.

James learns much about birds, but barely enough from them to keep himself alive, even after the war. The women are wiser. Rose ponders the “unnaturalness” of humans, their separation from the rest of life—caused not, as we tend to think, by our awareness of death, but our fractured relationship with time, our refusal to yield to the rhythms of natural life. But only Enid, who comes to the conclusion that “getting life right is hopeless” and that forgetting is a skill “you have to work at,” fully internalizes the theme that ran through Nocturne: The only presence we can count on in our lives is our own. Nature’s true lesson, in this ultimately hopeful novel, is: move on.