An amazing, inventive, hilarious kids’ book about—dementia?

Comedian David Walliams—that guy behind the cult hit ‘Little Britain’—is now becoming even better-known as an author of children’s books

Share

As the comedic force behind the TV show Big School as well as the absurdist sketch comedy series Little Britain (along with Matt Lucas), David Walliams is something of an established brand in Britain’s entertainment industry. Heck, Walliams has more than 1.6 million Twitter followers, and he’s celebrity enough to be a judge on Britain’s Got Talent.

Yet for kids, none of that matters. To them, David Walliams is famous for his amazingly adventurous, flamboyantly mischievous, hilariously serious books aimed straight at the children’s market—ages 8 to 12, and beyond. But while his eight novels have sold more than 12 million copies, with the first four adapted for TV, he’s drawn precious little attention on this side of the Atlantic. That’s changing. His newest book, Grandpa’s Great Escape, comes with a big publicity push. And deservedly so: Grandpa’s Great Escape is a heartwarming, charming tale of the love between a grandfather and grandson, injected with Walliams’s trademark mix of oodles of comedy, a dash of daring exploits, as well as a remarkably straightforward discussion of very adult issues.

“I want a sense of the forbidden, that it’s a book you would read under the bedclothes,” he explains in a phone interview from London. That means tackling a serious subject—in this case, Grandpa has dementia. “It’s difficult to see anything that would be child-friendly in that,” the author explains, “but then I had the idea: somebody who has dementia, who thinks they are in their past, they are almost playing. Well, children play. Maybe the only person who could understand this character would be his grandson.” During the Second World War, Grandpa flew Spitfires as Squadron Leader Bunting of the Royal Air Force. So five decades on, it was possible that a nattily dressed, elaborately moustached elderly Bunting would reenact battles with his grandson, Jack. “Grandpa thought it was real, but Jack would play along with it.” (Jack’s parents are distinctly secondary figures: his father is an accountant while his mum sells cheese.)

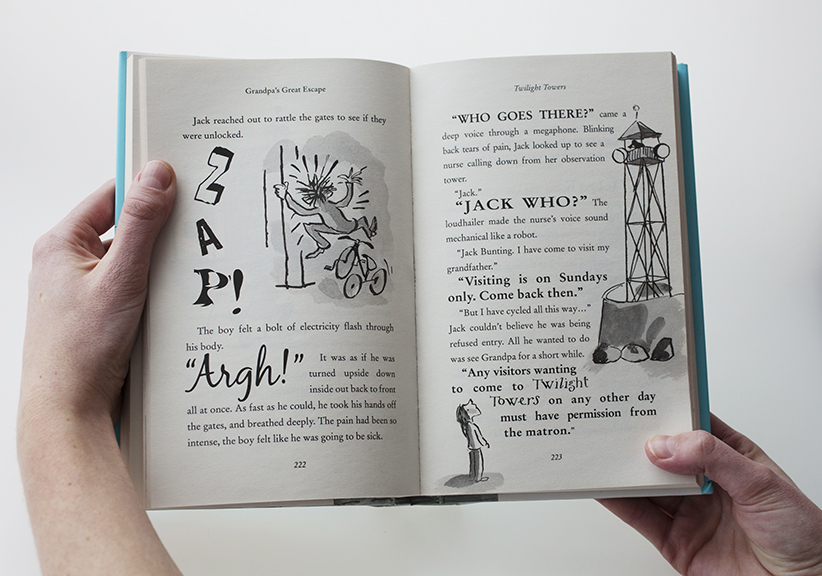

The author also incorporated ideas he’d had for a while, recreating The Great Escape in a seniors’ home, as well as adding a touch of malevolent evilness from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Thus was born Twilight Towers—”Caring for your unwanted old folk”—a converted Victorian lunatic asylum with guard towers and bars on the windows, where Grandpa finds himself incarcerated. The matron, Miss Swine, employs uncommonly large, hairy and tattooed nurses to keep seniors in, and to keep outsiders firmly out (except for a 15-minute visit each week).

Then there’s Adventure (with a capital A) in the form of a Spitfire plane, used by a small group of RAF pilots to hold off a Nazi invasion during the Battle of Britain, later flown by Bunting and Jack. Since the author wanted to write authentically about the “ecstasy of flying a plane like that,” he convinced his publishers that some real-world experience was needed, courtesy of a trip in a two-seater Spitfire. It was “like being in a Ferrari in the air,” he recalls. Over the water of the English Channel near Portsmouth, he and the pilot pushed the Spitfire, doing loops, dives and whirls, even speeding towards the cliffs, before performing a breakneck turn at the last minute. “The sense of freedom that people have when they fly—I wanted the flying to be a big part of it.” (He’s so proud of his flight that pictures are on the inside back cover, along with those of his own grandfather, who served in the RAF during the Second World War, though not in a Spitfire).

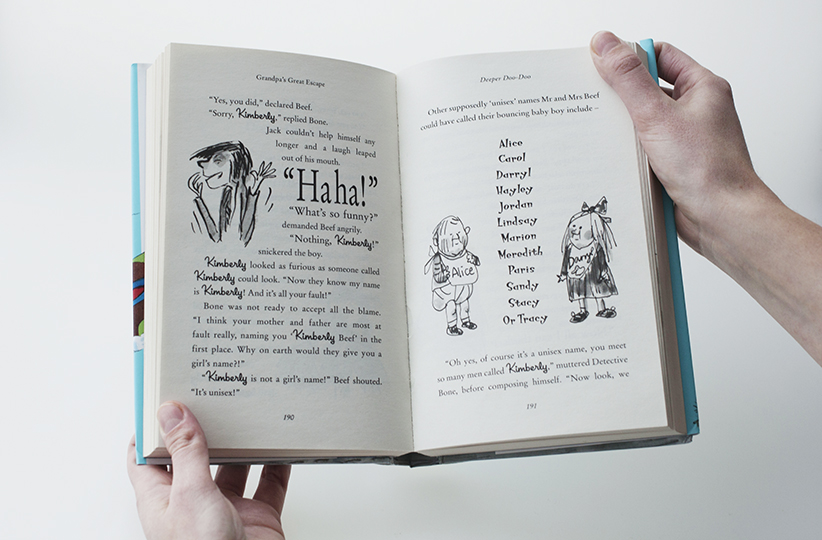

Walliams’s intricate plots are complemented by delightful illustrations and a refreshingly bold attitude towards type and and text. “When I go into schools, often I say, ‘Who doesn’t like reading? Who finds books boring?'” he says. “Sometimes that brave boy puts his hand up, feels a bit sheepish. I want to write books for those boys—it’s normally boys–because I don’t want them to get left behind. They think books are boring—’It’s just words on a page.’ I want this book to be much more user-friendly than that. I want it to have pictures and be very playful with the typeface.” There are myriad maps, lists, instructions and diagrams, as well as drawings of characters, including those rather big, scary nurses, all bestowed with dainty floral monikers, such as Nurse Primrose and Nurse Violet.

Walliams’s second career as a children’s author (or third, or fourth career—it depends how you count) came in 2008 when he had an idea for a story: What would happen if a boy went to school one day dressed as a girl? The Boy in a Dress, which explored issues around school-aged cross-dressing, was “nicely reviewed,” recalls Walliams, but not a hit. But he was hooked on writing for a young audience. Indeed, it wasn’t until his fourth book, Gangsta Granny—about an old grandmother who’s an international jewel thief determined to steal the Crown jewels—that sales took off. He’s written four more since, and along the way, nabbed two National Book Awards in Britain, and a growing legion of fans.

“The only limits with a children’s book are your imagination,” he says, “because children will go on this journey with you, wherever you take them.” There is one rule, though: Don’t bore them. Walliams has found kids to be much tougher critics. “I think grown-ups finish boring books that they feel they should read because it won an award, or whatever. From page one you are bored out of your mind. By page 895 you have no idea what’s happening. You are plowing on because you think, ‘Something is going to happen at some point.’ ” Not so with children. “If they find something boring, they will tell you.”

Walliams, whose favourite children’s author is Roald Dahl, is having the time of his life, especially when he talks to kids in schools. “I love doing it,” he says. “It’s very exciting to have a young audience of kids who like what you’re doing.” And with a growing audience comes something that caught Walliams off-guard: increasing pressure to outdo his last work. “It’s not, ‘I can just write what I want, people will like it,’ ” he says. “Now I can’t disappoint this young audience who really expect this new book to be better than the last.” With his latest, Mr. Walliams has no reason to worry.