The life of a uniquely seductive singer

Plus a biography of the Bhagavad Gita, what the endangered Great Bear Rainforest has to teach us, investigating men, and the original Siamese twins

Share

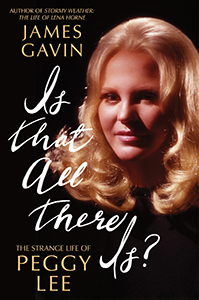

IS THAT ALL THERE IS? THE STRANGE LIFE OF PEGGY LEE

James Gavin

Gavin’s oeuvre may be lean, just four books across 23 years; but, to borrow a sentiment from Spencer Tracy, “what’s there is cherce.” Gavin numbers among that rare breed of biographer capable of tremendous style and substance, meticulous about detail and accuracy yet blessed with exceptional storytelling élan. He has a penchant for challenging subjects, previously illuminating the shadowy path of Chet Baker and melting the icy mystique of Lena Horne. Never, though, has he tackled as cagey an icon as Peggy Lee, arguably the finest female pop-jazz stylist of all time, yet a woman of massive insecurities cocooned in layers of self-deception and aggrandized half-truths. It took Gavin five years to untangle Lee’s dense web, and what emerges is a masterwork of balanced reporting, unflinchingly honest yet eminently respectful.

Lee’s story begins in the barrens of North Dakota, her early years shaped by a sweet but alcoholic father and a cold stepmother who would subsequently emerge as the bête noire of the singer’s self-spun mythology. Lee’s escape was music. Performing on regional radio stations led her to L.A., then Chicago, where she caught the attention of Benny Goodman. Her tenure with Goodman’s orchestra was brief, interrupted by marriage to guitarist Dave Barbour and retirement from showbiz. Though Barbour would prove to be her grand amour (three later marriages were short-lived and inconsequential), their relationship was derailed by his alcoholism and her rekindled desire for stardom in the 1950s and early ’60s, as a darling of chic supper clubs and variety series.

She could be as intense a tragedian as Billie Holiday (whom she was, early on, accused of parroting) and as sunny as Doris Day, but Lee’s specialty was a unique seductiveness, at once lusty and kittenish, that enabled her to thrive long after her contemporaries, even Sinatra. And she was, in various ways, a pioneer: among the first female singer-songwriters; an early apostle of new-age thinking; and, albeit somewhat reluctantly, a feminist before the term or movement existed.

She could also be a tyrant, burning through a litany of assistants and household staff. By the 1970s, though barely 50, she’d taken to bed, victim of endless illnesses more imagined than real, rising only for concerts and recording sessions. She grew steadily angrier, needier and, fuelled by Valium and Seconal, befogged. But her musicality never faltered. As late as 1996, wheelchair-bound and breathless, her less-is-more coyness could ignite thunderous ovations. To the end she remained a paradox, summed by playwright and collaborator William Luce as “the little girl you wanted to protect and the tough-as-nails lady who could destroy you with a few words.”