Book review: Toni Morrison’s violent new novel

Morrison’s new book erases barriers between the lofty African American novel and contemporary urban lit

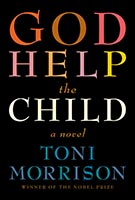

FILE – This 2012 photo released by Alfred A. Knopf shows author Toni Morrison. The Nobel laureate Morrison has a new novel coming next spring. “God Help the Child” will be released April 30, 2015, publisher Alfred A. Knopf announced Tuesday, Dec. 2, 2014. (AP Photo/Alfred A. Knopf, File)

Share

God Help the Child

Toni Morrison

If you listen to Chet Baker while you read Morrison’s new novel, as I did, you’ll find that your inner ear follows your outer ear, that the sound and shape of the story—the lonely, plaintive voices of the characters—echo the aching arc of the music, the voices sometimes colliding, producing a harsh dissonance, at other times coming together in a beautiful, haunting sound.

Booker, a central character in God Help the Child, plays trumpet. A scholar of economics, he finds music is the only way he can console himself over the death of his brother, murdered by a pedophile. Then he falls in love with a successful cosmetics executive, the gorgeous Bride, who shows off her blue-black complexion by wearing only white. Growing up, her blackness was a burden; her fair-skinned mother could barely stand to touch her, only accepting her when she helped to put a pedophile behind bars. Booker, on the other hand, loves her unconditionally. When he disappears she sets off on a quest to find him.

In plot and style—not to mention the curse words—God Help the Child deliberately erases barriers between the lofty African American novel and contemporary urban lit. Morrison is generally known as a historical writer, but her oeuvre actually comprises an unchronological journey through the whole of African American experience. At 84, she seems anxious to speak to the current generation.

There are some differences from previous works: This novel shifts focus from the Midwest to California. But Morrison’s heart remains the same. Her fairy-tale characters—here it’s Bride, whose body changes back to a child’s— travel outside their own reality, and their new reality is almost always symbolized by a small community, blessedly free of capitalist mores. In her search for Booker, Bride winds up staying with a hippie couple. Later she encounters Booker’s aunt, who lives with simple abundance in a mobile home. There are other interesting characters: Rain, the sexually abused girl taken in by the hippie couple; and Sofia, a teacher convicted of molesting children.

Most of the violence—and there is plenty—revolves around the sexual abuse of children. This is another of Morrison’s themes, central especially to The Bluest Eye and Love. It represents a brutal past not unlike that of racism or slavery. But this novel’s title recalls God Bless the Child, a Billie Holiday song about children—about all of us really—and our will to survive. It’s about the human ability to overcome and, despite her harsh vision, Morrison insists we can.