Canada Reads and what makes a book great

Michael Petrou considers the criteria for the CBC’s annual book competition

Share

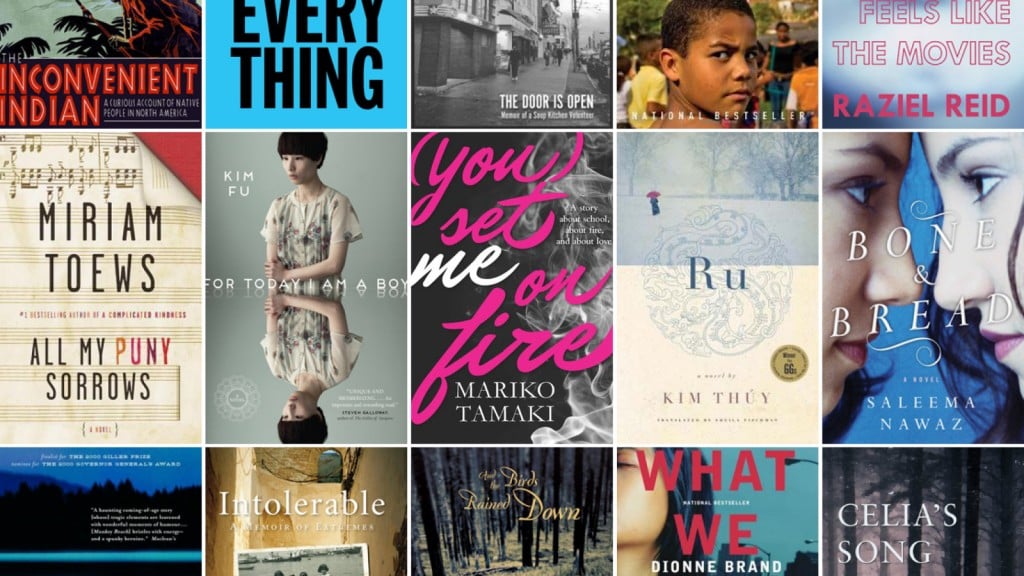

CBC’s 2015 Canada Reads competition, which released its long list today, has the tagline: “One book to break barriers.” It sounds like a line someone might have come up with after watching The Lord of the Rings (“One ring to rule them all … etc.), but never mind. The slogan is the least of its problems.

There was a time—roughly from when The Epic of Gilgamesh was composed until a few years ago—when books were judged on their literary merit. That’s not entirely true, of course. In authoritarian societies throughout history, writers and other artists were expected to produce works that buttressed an official narrative approved by the state. At times that led to brilliantly subversive art that was nuanced enough to get by censors but still resonated with an audience that understood its deeper meaning. Such a happy result, however, was a byproduct of imposed ideological constraints, not its intended effect.

The CBC is not doing anything that approaches Soviet censorship. No one is forbidden from writing anything. But only certain kinds of writing can enjoy the unparalleled publicity afforded by a spot on Canada Reads. The lucky authors are those whose works, CBC says, “change perspectives, challenge stereotypes and illuminate issues.” These are all worthy goals, I suppose, although “illuminate issues” sounds a little vague. But none of them is a criterion for great literature.

What makes a book great is admittedly subjective. But the quality of writing should be considered paramount. Both George Orwell and Christopher Hitchens were sufficiently skilled wordsmiths to pull off writing short essays about brewing tea. Not many authors can manage the same.

Beyond that, I’d argue that good non-fiction rests on the depth of research, the use of original sources, and the strength and originality of the arguments made. Superb fiction is a different beast, one that is perhaps harder to define. Characters, plot, pacing—all these things are important, but are not sufficient. Sometimes what matters most is the impact a book has on a reader, the emotions it provokes: sadness, rage, wonder. Some books seem to express something you had previously felt but never been quite able to articulate.

The CBC instead has placed a primacy on the supposed betterment of those who read its chosen books. That’s a shame, because books don’t need to effect positive social change to be worth reading. Did Mordecai Richler change perspectives and challenge stereotypes? Not according many of his critics who believed he mocked Jews. Did Salman Rushdie break barriers? Certainly not with The Satanic Verses. I can’t recall a single character worth emulating in Martin Amis’s London Fields, but loved reading it. Sometimes it’s enough simply to be entertained.

There may be gems among the 15 books on the Canada Reads long list. But if so, let them be celebrated as such because of the stories they tell. Breaking barriers is a handy skill for a marriage counsellor or trade negotiator. An author’s task is something different.