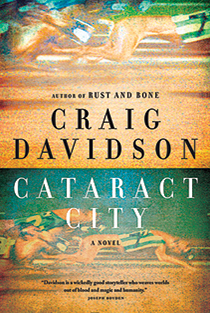

Cataract City

Cataract City

By Craig Davidson

Like most of his work, Davidson’s new novel is lurid, preoccupied with violence and masculinity, and set on the gritty, seedy side of southern Ontario—not the kind of fiction to earn conventional CanLit plaudits. And yet, his return to the literary big-time (since his 2006 Penguin debut, The Fighter, tanked, he’s been with small presses”) just may cement his wider appeal.

Last year, the Marion Cotillard film Rust and Bone transplanted two of his stories to southern France, made one of the protagonists a woman, foregrounded the characters’ humanity and won a standing ovation at Cannes. Cataract City, too, has unexpected layers beyond its pulpy exterior. Its two narrators live in Niagara Falls, far from the natural splendour and the tourist trap. They tread very different paths—the middle-class Owen becomes a policeman, the working-class Duncan finds employment outside the law—but they’re tethered together by a near-fatal boyhood trek through the woods, a passion for greyhound racing and a sense of inertia that maroons them in their hometown. Their pent-up frustration finds an outlet when they become determined to pursue a criminal operator who has wronged them both, heedless of their own safety. Still, there’s something noble in their perseverance and their conviction that, as Owen declares, “people can be more beautiful for being broken.”

Cataract City is indebted to genre fiction such as adventure novels and thrillers, and its many set pieces (depicting, for instance, pitbull-fighting, bare-knuckle boxing, embalming, a demolition derby and the effects of frostbite) are often savage. But Davidson balances his headlong plotting with fresh, poetic language and finds fascinating details in even the most morbid scenes. Moreover, his exploration of bromance, violence and thwarted dreams can be both bracing and poignant.

Owen’s and Duncan’s voices sometimes sound suspiciously alike, their descriptions overloaded with imagery, but the ardent prose nonetheless fuels the book’s rare intensity, its sense of compulsive storytelling. Like Bruiser Mahoney, his protagonists’ unhinged childhood wrestling idol, Davidson grabs readers in a chokehold and won’t let go. It’s unsettling and, best of all, it’s outrageously fun.