Chester Brown makes old sand-and-sandals Bible reruns riveting

Acclaimed graphic novelist Chester Brown on the Bible

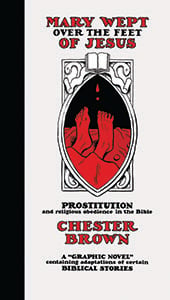

Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus by Chester Brown. No Credit

Share

MARY WEPT OVER THE FEET OF JESUS

By Chester Brown

The graphic novel has now reached enough maturity as a format for adult storytelling that it’s no longer necessary, perhaps, in a mainstream review, to draw attention to it. Except it should be noted immediately that Mary Wept Over The Feet of Jesus is composed of drawings that, in their spareness and economy, evoke the stripped-down language of the King James Bible. It can be awfully beautiful.

In retellings of the stories of Cain and Abel, Bathsheba and Ruth, the Annunciation or Job, Brown—a Canadian cartoonist whose script deftly combines arcane and contemporary English—makes the old sand-and-sandals Bible reruns riveting again. “Meanwhile, in Heaven, the angels are hanging out,” he writes at one point, just prior to a panel of winged creatures loafing, and it’s as if John Milton had grown up reading Superman.

If only every crank could look and sound this good. Brown is certainly one. Mary Wept centres on Bible stories featuring prostitutes, or women who advance their own interests by providing sex, and it makes a number of deeply outrageous claims about the most important figures in scripture—most explosively about the Virgin Mary.

Those claims, which interested, strong-stomached readers should have the pleasure of uncovering for themselves, are supported by a textual afterword, which is itself very elaborately footnoted. Brown makes reference to learned commentaries on Testaments Old and New, and advances bold, occasionally pretty far-fetched arguments about the history of Christianity and the Bible. That sometimes makes for exhilarating reading, but not always. The conjecture begins to grate.

Brown describes himself as a Christian, and he is best known for his graphic-novel masterpiece on the life of Louis Riel, who was also unorthodox in his approach to ecclesiastical matters. Mary Wept arrives as a sort of sequel to Paying for It: A Comic Strip Memoir About Being a John, which as its title suggests is an account of Brown’s decision to opt out of romantic love as a personal aspiration, and to begin hiring prostitutes. In Mary Wept, this Christianity is a form of anarchism that sees God as uninterested or even antagonistic to strict adherence to religious law, a God that sees love as the only real commandment. His Biblical women are paragons of savvy in the midst of oppression, and his renditions of these stories make the Bible an elemental exploration of gender discrimination. Brown here is, as always, an original thinker, and his take on the Good Book is oddly uplifting