City on Fire is a deeply engaging investment of time

The fall’s most anticipated fiction debut is also possibly its best-paid

No Caption

Share

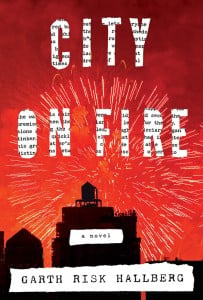

CITY ON FIRE

Garth Risk Hallberg

In an interview with The Paris Review, the late, great Mavis Gallant was asked whether her complete collected stories would ever appear in print. “There’s no point in a book that size,” she’d responded. “You can’t carry it; you can’t read it in bed; you have to put it on a table.” City on Fire is that kind of book—physically cumbersome at 927 pages, the sort of novel you’re inclined to prop on your lap rather than hold in your hands. But Hallberg’s book, with its thriller-like pacing and compassionate exploration of the values of art, is worth the lumbar pain it might give readers who haul it with them on their daily commute.

The novel offers an assortment of characters, all of whom are connected to a shooting in Central Park on New Year’s Eve, 1976. There’s Mercer, a young black teacher from the South, and his boyfriend, William, a troubled artist and musician. There’s William’s sister, Regan, and her estranged husband, Keith. There are Samantha and Charlie, teenagers from the suburbs who share a love of Patti Smith and all things punk. Others are folded into the mix, including William and Regan’s villainous stepmother and step-uncle, and a group of anarchists led by a guy who calls himself Nicky Chaos.

For all its focus on the punk scene and ’zines and the avant-garde, City on Fire is a fairly traditional social novel, exploring the thrilling sense of change and possibility that connects each person in this metropolis. This is 1970s New York, and all sorts of crimes occur: corporate espionage, insider trading, arson, assault. The events culminate in the blackout of July 1977, though timelines shift, so that sometimes we’re taken back a few hours, sometimes decades, and, at other times, we’ve leapt forward to a period just past 9/11.

Hallberg received a reported $2-million advance for City on Fire, making this one of the most anticipated debut novels in years. The book has its weaknesses: Dialogue is not Hallberg’s forte, and the length ultimately feels unnecessary. But faults aside, this is a deeply engaging investment of time, worthy especially as a display of Hallberg’s outsized ambition. His goal seems not unlike that of Mercer, an aspiring novelist who daydreams about someday explaining himself in his own Paris Review interview: “I wanted to explore again the old idea that the novel might, you know, teach us something. About everything.”