My lover the convict: The allure of incarcerated men

Diane Schoemperlen’s tortuous six-year relationship with a convicted killer

Share

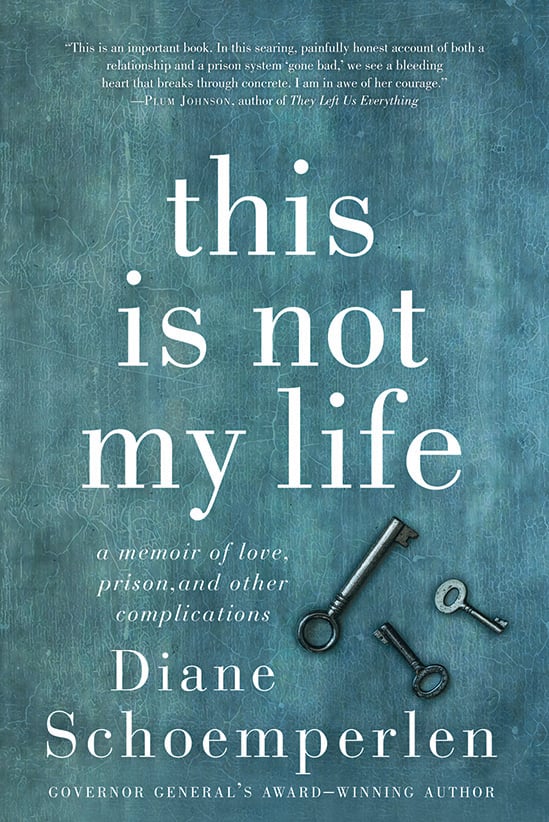

This is Not My Life

This is Not My Life

By Diane Schoemperlen

“It is safe to say that never once in my life had I dreamed of being in bed with a convicted killer, let alone one with his teeth in a margarine container in the kitchen, his mother in the next room, and the word Hi! tattooed in tiny blue letters on his penis.” So begins—or rather gallops— Schoemperlen’s riveting, often confounding account of her tortuous six-year relationship with a man she fell in love with when he was nearing the end of a three-decade sentence for second-degree murder.

The book sheds light on the allure incarcerated men have for some women, including Governor General’s award-winning novelists—a world in which Paul Bernardo can find a fiancée. The author met Shane in 2006 while volunteering at a charity meal program in Kingston, Ont., where he washed dishes. “I didn’t intend to fall in love with him, but I did,” she writes. Yet falling in love requires intent, especially when one party is behind bars. Shared interests were ferreted out: reading, word games, taking naps. “Don’t we all do this when we fall in love—don’t we all look for signs of ourselves in the other,” she writes. “You can always find them if you look hard enough.” Both had been scarred in childhood, told they weren’t good enough.

Schoemperlen ignored scarlet flags and friends’ warnings. Shane became her noble project, she writes: “I could shine my light and lead him out of the darkness.”

Prison life—the society, the bureaucracies, the difficulty integrating life inside the prison with that outside of it, worsened by the Harper government’s “tough on crime” agenda—is rendered vividly. But Schoemperlen is at her most compelling in teasing out the universal truths in her unusual liaison. Prison visits can be ideal for courtship: “I can think of no comparable situation in the free world where a couple has so much time simply to be together and talk,” she writes. Shane’s inmate status was a convenience: “With him in prison I thought I could have a partner and maintain my independence too.” She found solace that Shane “came with paperwork outlining all of the terrible things he’d done in his life, whereas with a regular guy you just had to figure out what was wrong with him as you went along.”

Going along, Schoemperlen found plenty wrong, shockingly so. Yet she persevered in the name of “love” until she realized she was the one in darkness: “I was in love with the story of my relationship with Shane,” she writes. “That was beautiful, tender, romantic, the reality is not.” Now those two narratives are nimbly rewoven into a tale that, in extremis, exposes the human need and wilful blindness that underlie all doomed love stories, inside prison and out.