Do women writers have ‘literary cooties’?

A remarkable study of the kinds of books that win big prizes reveals this: Don’t write about women. Unless, that is, you’re a man.

Stack of award winning books. Photograph by May Truong

Share

Since the playwriting contests of Ancient Greece, when the prize “was a goat, plus, of course, prestige,” in the dry summation of English professor Owen Percy, the writing world has obsessed over literary awards. Now, when prizes that can stretch to six figures dominate the literary scene more than ever—vastly influencing what readers hear of, as well as writers’ public profiles, career arcs and bottom-line ability to feed their children—the obsession is more intense than ever. But among the endless rumours of awards jurors out to promote friends or skewer enemies, and the fretting that ambitious authors will “write to the prize,” critics have always taken the gossip and theories as personal opinion. Hard data is not something the book world has ever sought out, or even believed was available.

Yet it’s there, lying hidden in plain sight, argues novelist Nicola Griffith. Put in terms of practical advice for anyone actually trying to write for a prize, it comes out this way: Don’t write about women. Unless, that is, you’re a man.

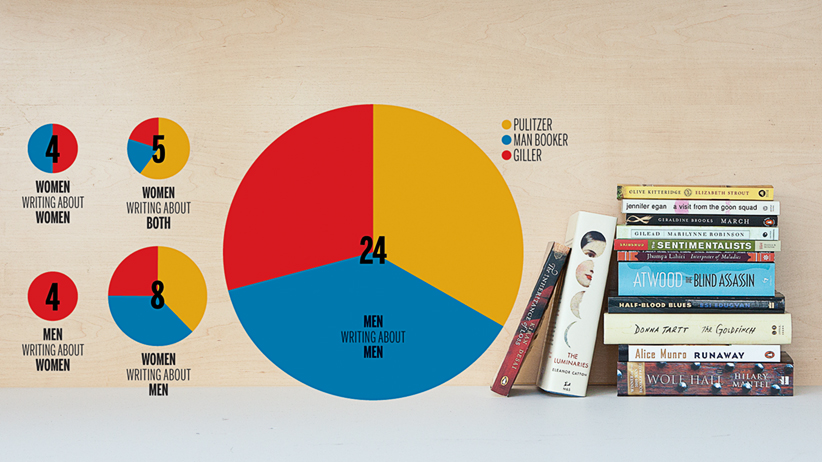

Griffith, a Briton long resident in Seattle who frequently writes within the science-fiction fold, had a close look at the 21st-century results of five major American and international prizes, and one award in children’s literature. The results, as published on her blog, are eye-opening. Fifteen winners of the Man Booker Prize, perhaps the Anglosphere’s most prestigious, divide into nine men and six women, that is to say, already slightly skewed in gendered balance, albeit within random coin-tossing territory. But all nine of the men wrote primarily about male characters, as did three of the women winners, while a fourth had multiple points of view. Only two women authors provided primarily female POVs.

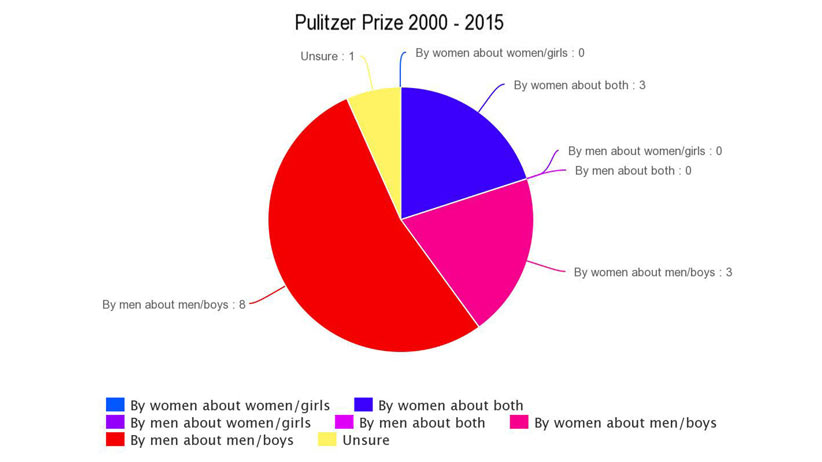

Accident? The Pulitzer prize was zero for 15 for women writing about women. Nine male winners stuck to their own chromosome, three female winners took on male characters, and the other three had multiple POVs. The others mostly fell into line, although the Hugo, as befits a major science-fiction prize, was a little looser—nine male winners included three authors writing about both sexes. Even there, though, the five female winners broke down as usual—two on women, two on men, one on men and women.

Significant difference had to wait for the Newberry award, handed out annually by American children’s librarians for achievement in Children’s literature. For starters, women authors—reflecting their prominence in the genre—dominate the winners, 10 to 5. And it’s the men who act like the minority sex does in the adult lists—three of five male winners had primarily female perspectives, while only two female writers had male POVs. In Griffith’s judgment, the message is unmistakable: “Girls are interesting, women aren’t.”

All told, the five adult awards named 75 winning books this century, 44 by men and 31 by women, a 3 to 2 ratio, showing that women authors win a solid, if not equal, share of the loot. But none of the men wrote primarily from a woman character’s point of view, although a handful had multiple POVs, including women’s. Among the female authors, 24 wrote from a mixed or primarily male POV. That means a mere seven—less than 10 per cent—of the 75 books that took home some of the Anglosphere’s most prestigious literary awards were written by women about female lives. Griffith’s blunt conclusion: “The literary establishment doesn’t like books about women; women have literary cooties.”

Griffith’s blog post stirred up reaction around the world. Author Kamila Shamsie, citing Griffith’s data, for one, argued in the Guardian for a radical response to publishing’s bias against women. One publisher responded with a pledge to accept no books from male writers for a year. “This morning I heard from a woman in New Zealand who’d had a look at her national prize lists,” she says in an interview. “She wasn’t pleased with what she saw.” That’s the sort scrutiny Griffith wants to see happen, a looking past the dust jacket photos, past the 40 per cent or so of prizes that go to female authors, to just what sorts of books that are rewarded. “I want more data. I want to know what kind of manuscripts are submitted to publishers, which ones are accepted, which ones are promoted, which ones are assumed to represent what interests readers.”

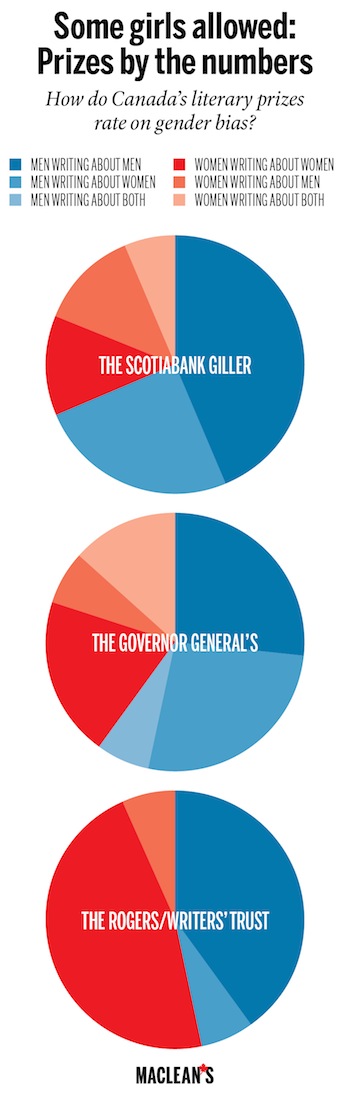

So what of Canada, where the English-language literary icons are two women—Alice Munro and Margaret Atwood? When Maclean’s looked at Canada’s major prizes (Scotiabank Giller, Governor General’s, Rogers/Writers’ Trust) the results were, well, Canadian—fence-straddling with a vengeance. The trends were visible but not as pronounced. The three prizes handed out 46 awards (the Giller had two winners one year), 26 to men and 20 to women, meaning the raw male-female ratio was better than in the U.S. And the tendency of female authors to adopt male or multiple POVs was marked—13 out of 20—but less extreme. Where the Canadian results diverged most sharply, though, was in the relative willingness of Canadian male authors to adopt female POVs—nine prize winners, albeit representing seven books, since two (Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost and Clara Callan by Richard Wright) were multiple winners. In short, women writing on women didn’t fare much better in Canada than elsewhere, but Canadian male authors did.

So what of Canada, where the English-language literary icons are two women—Alice Munro and Margaret Atwood? When Maclean’s looked at Canada’s major prizes (Scotiabank Giller, Governor General’s, Rogers/Writers’ Trust) the results were, well, Canadian—fence-straddling with a vengeance. The trends were visible but not as pronounced. The three prizes handed out 46 awards (the Giller had two winners one year), 26 to men and 20 to women, meaning the raw male-female ratio was better than in the U.S. And the tendency of female authors to adopt male or multiple POVs was marked—13 out of 20—but less extreme. Where the Canadian results diverged most sharply, though, was in the relative willingness of Canadian male authors to adopt female POVs—nine prize winners, albeit representing seven books, since two (Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost and Clara Callan by Richard Wright) were multiple winners. In short, women writing on women didn’t fare much better in Canada than elsewhere, but Canadian male authors did.

Nor is she much impressed with the male outliers on the Canadian lists. American awards have seen the same, she points out, recalling how Michael Cunningham’s Virginia Woolf-like The Hours, in which Woolf herself is a character, won the Pulitzer in 1999. “Women do become interesting when men write about them; when a woman does, it becomes a ‘domestic’ novel.” Such male writers do seemed to be rewarded, though, perhaps because of their relative rarity. “Women are more likely to write about men than the reverse because women know a vast amount about men,” says Griffith, because in terms of historical power relationships, “they have had to in order to survive.”

Even the greater gender balance, rising to female dominance, in the children’s and Young Adult genres, doesn’t indicate a better future. It’s more apparent than real, she believes. “The Ladybusiness site ran an analysis in 2012 of YA prizes around the world and found that although 56 per cent of the winners were women, only 36 per cent of the protagonists were.” Nor can the devaluation of women’s stories be pinned on the small groups of jurors involved in each decision, given that the Hugo is awarded by popular vote.

And when she looks further up the literary prize food chain, Griffith sees the opacity that cloaks women’s writing slip away. In Canada, the Scotiabank Giller, the grandest of national literary awards had the greatest gender imbalance—11 men to five women, a 2-1 ratio. That accords with what the writer argues is the overarching trend revealed by the data. “The more prestigious the prize, the more likely it is to come out that way,” says Griffith. It’s a matter of our ingrained cultural expectations, she adds. “It’s not that women are uninteresting, but the way they live their lives is.”