A gay utopia in Weimar-era Berlin: Book review

Author Robert Beachy explores Berlin’s gay culture and sexually liberal history

Share

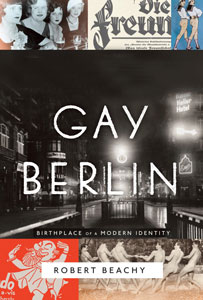

Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a modern identity

Robert Beachy

German history is not a place one usually looks for evidence of unprecedented tolerance toward minorities. The atrocities of the Second World War, committed under a Nazi regime that murdered six million Jews and sent up to 15,000 homosexuals to concentration camps, have permanently altered the German sensibility; today, despite living in a socially liberal country, many Germans tend to walk on eggshells where issues of cultural diversity are concerned.

But, according to Beachy, a historian, Germany—and Berlin, in particular—was a surprisingly sexually liberal place shortly before Nazism took hold. Beachy’s book is an exhaustive history of gay culture there from the mid-1800s, when prolific author Karl Heinrich Ulrichs published his groundbreaking and controversial pamphlets on same-sex love, until the 1930s, when Hitler’s operatives raided their own ranks for homosexuals. Ulrich, an openly gay intellectual whose family appeared to love and accept him despite their personal objections to his sexuality, was, many believe, the first gay man in recorded history to defend homosexuality in a court of law. (In 1867, he urged the repeal of anti-gay laws.) “Although his theories were largely spurned by the German medical establishment,” writes Beachy, referencing Ulrich’s eccentric theories about homosexuality as a form of “psychological hermaphroditism . . . he influenced a group of progressive psychiatric and legal professionals to accept the idea that same-sex love was an inborn phenomenon, not simply a vice, a perversion, or a traditional sin.”

This is a concept not yet embraced by millions in the modern United States, yet it was accepted in parts of 1920s Berlin. Gay life in Berlin under the Weimar Republic wasn’t a foreboding prologue to a Nazi takeover, but a great time: Gay journals and periodicals were sold openly on the streets, and gay bars flourished with little crackdown from police. It wasn’t until the mid-1930s, after high-ranking Nazi leader Ernst Röhm (a well-known homosexual) was murdered by his own party that the Nazis began targeting “Aryan” homosexuals. A year after Röhm’s murder, writes Beachy, Heinrich Himmler established the Reich Office to Combat Homosexuality and Abortion—and a moment of rare tolerance came to a horrific end.