Governor General’s Literary Awards: 2019 English-language winners spotlight

We spoke with the winners of all seven 2019 English-language Governor General’s Literary Awards. Here’s what they had to say about the honour, and how their work fits in with the Canadian narrative today.

Share

In partnership with the ![]()

National recognition for Canada’s best writers was a long-standing goal of the Canadian Authors Association, founded in 1921 by the likes of Stephen Leacock and John Murray Gibbon, when a spectacular opportunity arose in 1935. The new Governor General, Lord Tweedsmuir, was the first of the monarchy’s viceroys in Ottawa to have been raised to the peerage for that exact purpose. In his days as a commoner, he was Scottish novelist John Buchan, author of the internationally popular thriller The Thirty-Nine Steps. With a sympathetic ear in Rideau Hall—Tweedsmuir also established the official residence’s first proper library—the Governor General’s Literary Awards began life in 1936. Actually, in 1937, which was when the first two winners were announced for books published the previous year: Bertram Brooker’s novel Think of the Earth, for fiction, and journalist Thomas Beattie Roberton’s essay collection T.B.R.: Newspaper Pieces, for nonfiction.

As the inaugural prizes indicate, the nation’s oldest and most storied literary awards have evolved every bit as much as—and in tandem with—Canadian literature itself over the eight decades since. The awards are now given to works in the years the books were published (usually), and they are no longer only for texts in English, whether originally or by translation. The Canadian Authors Association’s decision that dramas be ineligible for consideration, on the basis they should be judged by their stage productions rather than their printed forms, was long ago dropped as the number of categories honoured expanded from two to its current seven. The biggest single year of change was 1959, when the awards passed from the CAA to the Canada Council for the Arts, the national public arts funder. The Canada Council immediately established a parallel list of prize categories in French, and ensured drama was one of them in both official languages.

The Governor General’s Literary Awards have flourished under the Canada Council’s administration, funding and promotion. The prize money has steadily risen and is now $25,000 for each winner. In 1986, the council added translation, a key to bridging linguistic solitudes, as an art form to be celebrated, along with two awards—for text and illustration—in illustrated books, now known as young people’s literature. In 1979, GGBooks began the practice of announcing a list of finalists a few weeks before the announcement of the winner, bringing the award’s spotlight onto far more books. Contenders are now five in number for each award, whether French or English. The Canada Council’s website annually invites Canadians to “discover the 70 finalists for this year’s Governor General’s Literary Awards.”

What hasn’t changed from the beginning, though, is an interest in—and a commitment to—diversity, to an idea of Canada as a mosaic rather than a melting pot. Four of the first five GGBooks winners (poetry was the third genre entered into the mix) were born outside Canada as it then was, in Britain or Newfoundland. But it was the Winnipeg-born winner who came from outside the Anglo-Canadian mainstream. Laura Salverson, who won the 1937 fiction award for The Dark Weaver, was the daughter of Icelandic immigrants. She wrote often and movingly about the struggle to both avoid assimilation and find acceptance in Canada, winning a second nonfiction GGBooks award in 1939 for her autobiography, Confessions of an Immigrant’s Daughter.

Questions of identity, acceptance and equality—diversity, in short—continue to roil Canadian society and Canadian literature. They are on full display, along with much else, in the work of winners of the seven 2019 English-language Governor General’s Literary Awards. Ranging in age from 32 to 77 and spread out from Winnipeg to Halifax, the five women and two men cover a lot of ground indeed.

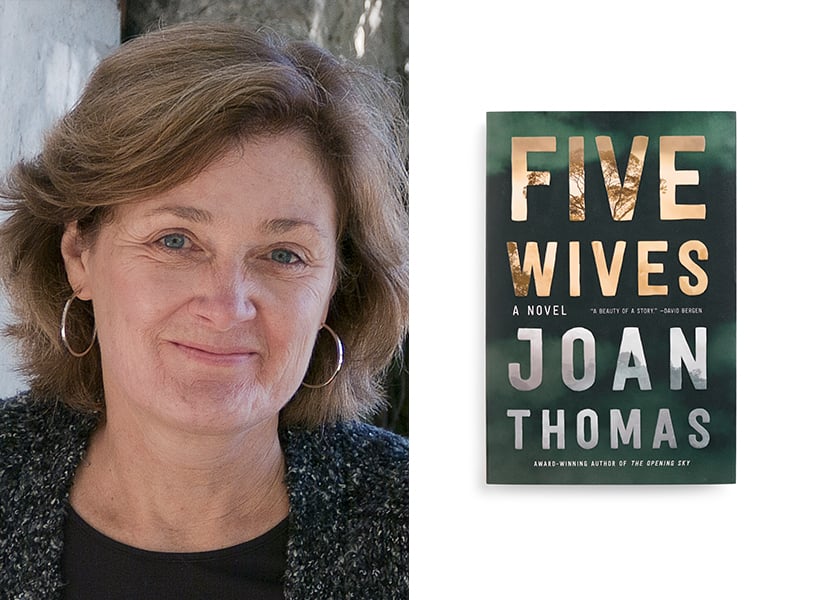

Fiction – Five Wives, Joan Thomas

Joan Thomas won the award for fiction, the most prestigious and highly publicized of the genres, for Five Wives, a fictionalized take on a real-life event. In 1956, a group of five evangelical Christian missionaries and their families came to the Ecuadorean rainforest to convert the Waorani, a people who had carefully and violently kept their distance from the outside world. The men spent some days dropping gifts from an aircraft before entering Waorani territory. They were all killed almost immediately, leaving behind five widows and nine children coping for themselves in a sudden glare of worldwide attention. “I grew up in a conservative Christian context where this story—especially as presented in the memoir of one of the wives, Elisabeth Elliott—was very alive and very revered,” says the Winnipeg author, 70, who was born in Carberry, 170 km from Manitoba’s capital.

Joan Thomas won the award for fiction, the most prestigious and highly publicized of the genres, for Five Wives, a fictionalized take on a real-life event. In 1956, a group of five evangelical Christian missionaries and their families came to the Ecuadorean rainforest to convert the Waorani, a people who had carefully and violently kept their distance from the outside world. The men spent some days dropping gifts from an aircraft before entering Waorani territory. They were all killed almost immediately, leaving behind five widows and nine children coping for themselves in a sudden glare of worldwide attention. “I grew up in a conservative Christian context where this story—especially as presented in the memoir of one of the wives, Elisabeth Elliott—was very alive and very revered,” says the Winnipeg author, 70, who was born in Carberry, 170 km from Manitoba’s capital.

A high school English teacher and prolific book reviewer for national media, Thomas came late to writing herself. “Novels had always been an unacknowledged ambition,” she says, “a huge leap of faith—eventually I put four years into my first, Reading by Lightning.” Published in 2009 when Thomas was 60, her debut won the Amazon Canada First Novel Award, and the three novels that followed have all been nominated for major literary prizes, including the Governor General’s Literary Award in 2014 for The Opening Sky. The story behind Five Wives—rooted, like the premises that underlie her other books, in her childhood milieu—never left Thomas’s consciousness even after she “moved away from that [religious] world.” After reading about the politics of oil in Ecuador and the destabilizing effects of missionary work on tribal communities, she began to think of it anew, from a secular perspective and from the perspective of five women who were always on the sidelines of a dominant storyline about male martyrdom. “I wanted to explore how the wives accepted that their husbands’ deaths should be celebrated as acts of God’s will, and how they—four of them, that is—came to carry on proselytizing among the Waorani. This kind of thinking about other people doesn’t go away, and the story kept feeling more and more timely to me. All historical novels are really contemporary novels.”

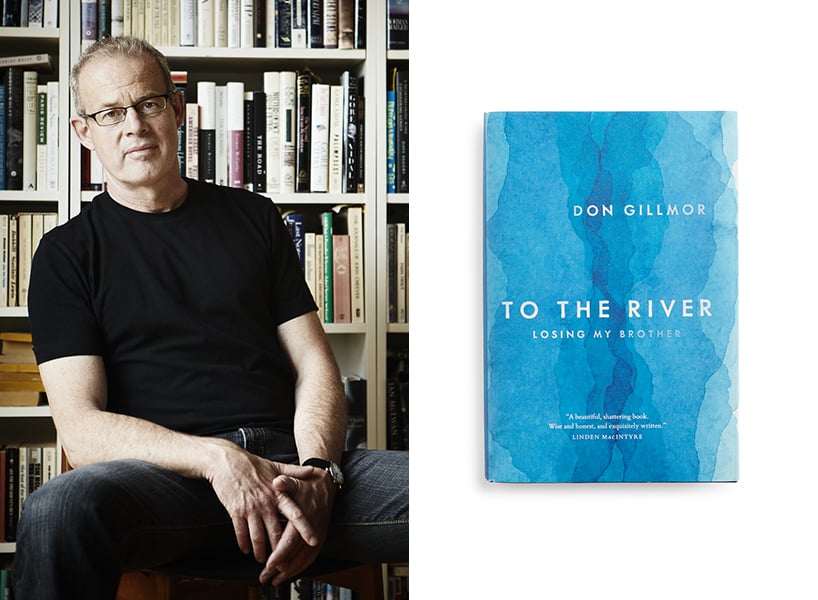

Non-fiction – To the River: Losing My Brother, Don Gillmor

Don Gillmor is the nonfiction winner for To the River: Losing My Brother. It’s a haunting, beautifully written exploration of his brother’s death that becomes a sustained meditation on suicide in the modern world. At age 48, in December 2005, David Gillmor parked his truck 30 km south of his Whitehorse home and walked into the Yukon River, not to be found for six months. It is a painful subject for those left behind. “Not easy at all to write about,” says the 65-year-old Toronto author, just as he “didn’t for a long time know what to say to anyone about David’s death.” By the time Gillmor had forced himself into and back out of the vast literature on suicide—all of which fails to find predictive power in its many patterns—he had taken to describing himself as “a wraith drifting around the suicide world.” There was good that came of the work though, as others opened up to him about their family or personal stories. “There’s still a steady trickle on my website,” months after publication, he adds, “some who have survived their attempts, but mostly those who have lost someone, all gratified to see their experiences in print.”

Don Gillmor is the nonfiction winner for To the River: Losing My Brother. It’s a haunting, beautifully written exploration of his brother’s death that becomes a sustained meditation on suicide in the modern world. At age 48, in December 2005, David Gillmor parked his truck 30 km south of his Whitehorse home and walked into the Yukon River, not to be found for six months. It is a painful subject for those left behind. “Not easy at all to write about,” says the 65-year-old Toronto author, just as he “didn’t for a long time know what to say to anyone about David’s death.” By the time Gillmor had forced himself into and back out of the vast literature on suicide—all of which fails to find predictive power in its many patterns—he had taken to describing himself as “a wraith drifting around the suicide world.” There was good that came of the work though, as others opened up to him about their family or personal stories. “There’s still a steady trickle on my website,” months after publication, he adds, “some who have survived their attempts, but mostly those who have lost someone, all gratified to see their experiences in print.”

Born in Winnipeg, Gillmor graduated from the University of Calgary in 1977 and soon embarked on the chancy career of a freelance writer. The recipient of numerous awards and award nominations for his journalism, Gillmor has also penned three critically acclaimed novels (most notably 2013’s Mount Pleasant, a corrosively dark satire on privilege and debt in upper-middle-class Toronto), a two-volume history of Canada and four other nonfiction works. That’s before mentioning his nine books for children, two of which brought him his other Governor General’s nominations. To the River is Gillmor’s first win. “The most prestigious, biggest prize I’ve ever won,” he says, and one with a “bittersweet” feel, given the book’s contents. “But I’m thrilled the subject is moving into the open, in the news as well as in recent fiction, because there is still a stigma that suppresses talking about suicide.” The more out there it is, Gillmor says—and the GGBooks’s nod will materially aid in that—“the more the stigma will fade.”

Poetry – Holy Wild, Gwen Benaway

Gwen Benaway won the poetry award for her third collection, Holy Wild. Its intimate, lyrical, confessional poems, all speak to the infinite complexities of being an Indigenous trans woman. Some of the writing is exhilarating in its linguistic flights, some dryly funny or drenched in irony; for Benaway in “White Passing,” finding acceptance isn’t a matter of “scrubbing brown off bodies,” but “tucking my dick even if it hurts.” None of it, however, despite its overt political nature, falls into didacticism. “Poetry is a language of resistance, of refusal, and of defiance,” she says, “a way of thinking through life. But unlike theory, poetry moves into feeling and being in the world. There’s a space in poetry, ‘a rupture’ as Dionne Brand calls it, where different ways of living and being become possibility. I write towards those possibilities. At the heart of it, I think writing and living are about trying to cultivate a loving but resistant heart that chooses to refuse injustice and fights for necessary change.”

Gwen Benaway won the poetry award for her third collection, Holy Wild. Its intimate, lyrical, confessional poems, all speak to the infinite complexities of being an Indigenous trans woman. Some of the writing is exhilarating in its linguistic flights, some dryly funny or drenched in irony; for Benaway in “White Passing,” finding acceptance isn’t a matter of “scrubbing brown off bodies,” but “tucking my dick even if it hurts.” None of it, however, despite its overt political nature, falls into didacticism. “Poetry is a language of resistance, of refusal, and of defiance,” she says, “a way of thinking through life. But unlike theory, poetry moves into feeling and being in the world. There’s a space in poetry, ‘a rupture’ as Dionne Brand calls it, where different ways of living and being become possibility. I write towards those possibilities. At the heart of it, I think writing and living are about trying to cultivate a loving but resistant heart that chooses to refuse injustice and fights for necessary change.”

At 32, the youngest of this year’s winners, Benaway grew up moving between Northern Michigan and Ontario’s Huron County. She currently lives in Toronto, where she is a doctoral student at the University of Toronto’s Women and Gender Studies Institute, as well as a poet and activist. Not that Benaway draws any sharp distinction between the varied aspects of her life. “I come from a tradition of trans women poets and artists who challenged dominant society through their work. I use poetry to speak to the discrimination and violence that trans women experience in order to hopefully create other possibilities for trans women around me.” For that reason, despite her wariness that individual honours can be less a sign of progress than the co-opting of “a chosen few into the power structure,” Benaway welcomes a GGBooks win she never expected. “It’s time for trans lives to be shown by trans writers through our individual perspectives and communities.” Besides, the poet adds, “it means that I won’t be homeless for a little while longer and will have some financial security for the next six months.”

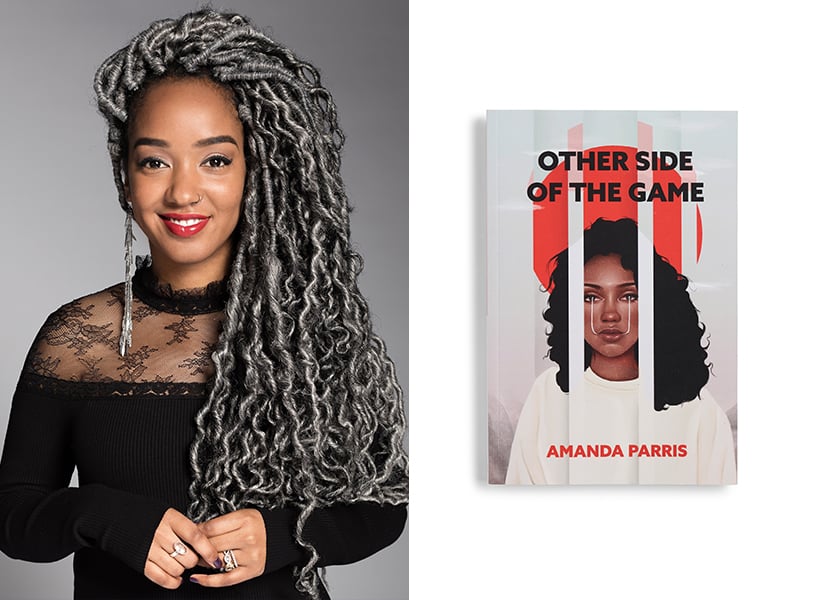

Drama – Other Side of the Game, Amanda Parris

Amanda Parris took this year’s drama award for Other Side of the Game. Set in the 1970s and in the present day—plus ça change being one of its themes—Parris’s first play is a passionate look at black women loyally standing by their incarcerated men. Her story was born, says the host of three CBC TV series and one CBC radio show, when she was in Toronto’s now-closed Don Jail to visit a friend, and encountered the milling line-up of women visitors there. As Parris started to talk with them, and then to tape their conversations, she became fascinated by the women’s side of what is always told as a men’s story. “Those women are ignored in most media. They told me they had never articulated their stories before—what they’ve gone through as parents and workers, the battles they’ve had with unjust institutions—because they had never been asked what they thought and felt.”

Amanda Parris took this year’s drama award for Other Side of the Game. Set in the 1970s and in the present day—plus ça change being one of its themes—Parris’s first play is a passionate look at black women loyally standing by their incarcerated men. Her story was born, says the host of three CBC TV series and one CBC radio show, when she was in Toronto’s now-closed Don Jail to visit a friend, and encountered the milling line-up of women visitors there. As Parris started to talk with them, and then to tape their conversations, she became fascinated by the women’s side of what is always told as a men’s story. “Those women are ignored in most media. They told me they had never articulated their stories before—what they’ve gone through as parents and workers, the battles they’ve had with unjust institutions—because they had never been asked what they thought and felt.”

The broadcaster, who was born in Britain and moved to Toronto when she was 10, has also been an educator in arts-based curricula, community activist and actor. Playwright, Parris says, is a natural development. Parris, 33, has thought of drama “as a way to tell all the stories stored in me” since an accidental encounter in Nairobi years ago. A performance of street theatre in four languages drew an entire neighbourhood out of their homes to watch. “I want those women’s voices, the language they use, to literally be heard and recognized,” she says. That’s why her Governor General’s win matters so much to her. “I’m still in a state of shock,” Parris says, “but knowing that this prize turns a spotlight on the women and their communities is a great affirmation of their lives and issues.”

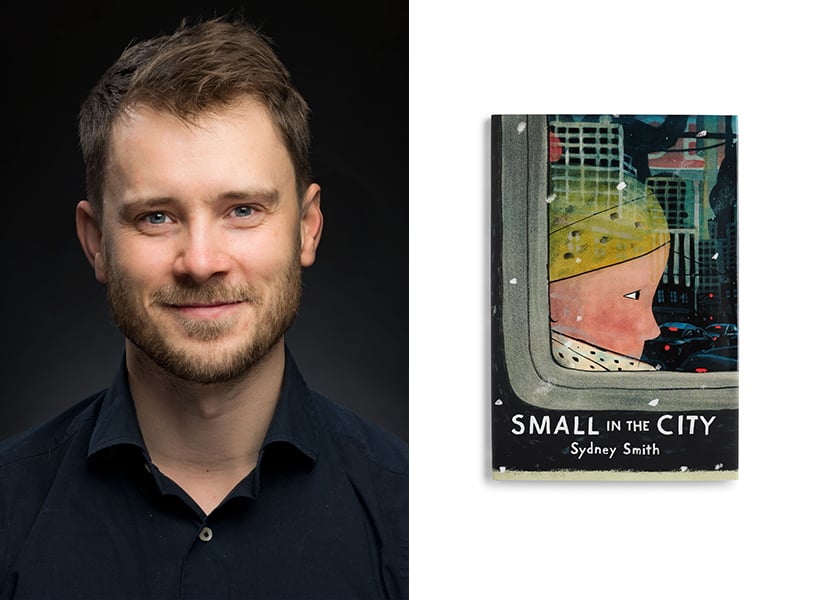

Young people’s literature, illustrated books – Small in the City, Sydney Smith

Sydney Smith is the winner of the illustrated books category in young people’s literature for the evocative watercolours, alternating between small panels and full spreads, in Small in the City, a book meant for readers aged three to seven. In an unnamed big city—albeit with very Toronto streetcars—amid a steadily increasing snowfall, a little boy walks through a downtown area, looking for someone or something very important to him. All the while, on busy streets or in quiet parks, he provides an ongoing internal commentary for the lost, offering tips for the people and places— from kind fishmongers to warm dryer vents—that make the city a friendlier place. “It is my old neighbourhood in Toronto,” says Smith, now back in his native Nova Scotia, “and maybe not the best one for kids to grow up in—lots of high fences and locked doors—but it can be mastered, just as the little boy assures someone who might not be as confident as him.”

Sydney Smith is the winner of the illustrated books category in young people’s literature for the evocative watercolours, alternating between small panels and full spreads, in Small in the City, a book meant for readers aged three to seven. In an unnamed big city—albeit with very Toronto streetcars—amid a steadily increasing snowfall, a little boy walks through a downtown area, looking for someone or something very important to him. All the while, on busy streets or in quiet parks, he provides an ongoing internal commentary for the lost, offering tips for the people and places— from kind fishmongers to warm dryer vents—that make the city a friendlier place. “It is my old neighbourhood in Toronto,” says Smith, now back in his native Nova Scotia, “and maybe not the best one for kids to grow up in—lots of high fences and locked doors—but it can be mastered, just as the little boy assures someone who might not be as confident as him.”

The Halifax-based illustrator, 39, is a rapidly rising star in his field. After graduating from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Smith began modestly enough as a designer of posters and album art for musician friends. His collaboration with Toronto poet JonArno Lawson, Sidewalk Flowers, saw him rack up a stream of awards over the last few years, including the 2015 GGBooks award for illustrated books. The artistic work has always matched “my artistic sensibilities,” says Smith, who still “secretly” loves his childhood practice of drawing monsters. “There are very few limitations to creativity. Children’s books let you go as far as you want. The more imagination the better.” Before his latest work, though, there were limitations—mostly enjoyable—arising from the “special chemistry of collaboration” with others’ words. Small in the City marks Smith’s first foray as an author as well as illustrator. Now that it too has won the Governor General’s award, the sky would seem to be the limit, although a cautious Smith demurs. “How,” he asks laughing, “am I supposed to top that?”

Young people’s literature, text – Stand on the Sky, Erin Bow

Erin Bow won the text award for young people’s literature, for Stand on the Sky, her exciting story for preteen readers of a sister, a brother and an orphaned baby eagle set in contemporary Mongolia. And why real-life Central Asia, given a previous writing history of Young Adult (YA) fantasy and science fiction? “I’ve always been fascinated with falconry,” Bow says, “and I had been brewing a falconry-and-sibling story forever. But I couldn’t make it work, mostly because I wanted a happy ending, and there seemed no way to get that in a North American setting. Then I saw photos of kids training eagles in Mongolia, a place where, uniquely, they let their eagles return to the wild while they’re still young, and the possibilities just leapt into my mind.”

Erin Bow won the text award for young people’s literature, for Stand on the Sky, her exciting story for preteen readers of a sister, a brother and an orphaned baby eagle set in contemporary Mongolia. And why real-life Central Asia, given a previous writing history of Young Adult (YA) fantasy and science fiction? “I’ve always been fascinated with falconry,” Bow says, “and I had been brewing a falconry-and-sibling story forever. But I couldn’t make it work, mostly because I wanted a happy ending, and there seemed no way to get that in a North American setting. Then I saw photos of kids training eagles in Mongolia, a place where, uniquely, they let their eagles return to the wild while they’re still young, and the possibilities just leapt into my mind.”

Born in Des Moines, Iowa, Bow married a Canadian and ended up in Kitchener, Ont., mostly inside a heated garden shed-cum-writer’s office. She was “always the kid with a nose in a book,” Bow says, “although writing never occurred to me as a career.” She loved science too and came out of university with a physics degree. That’s when she learned she liked reading about science a lot more than the hard work of doing it, and took to “making a living as a science writer.” Eventually, continues Bow, 47, the strands of her life began knitting together: “My first fiction was Dr. Who fan fiction.” She remains a science writer, through what she calls her “great half-time gig” as a senior writer/editor at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in nearby Waterloo, Ont., crafting newsletters and web articles for one of the world’s premier physics centres. As for working within the YA genre, Bow is adamant about the inevitability of that choice for her. “That’s the sort of literature I like reading myself, because of the emphasis on storylines. Like teens and kids, I can’t stand books that don’t tell a story.”

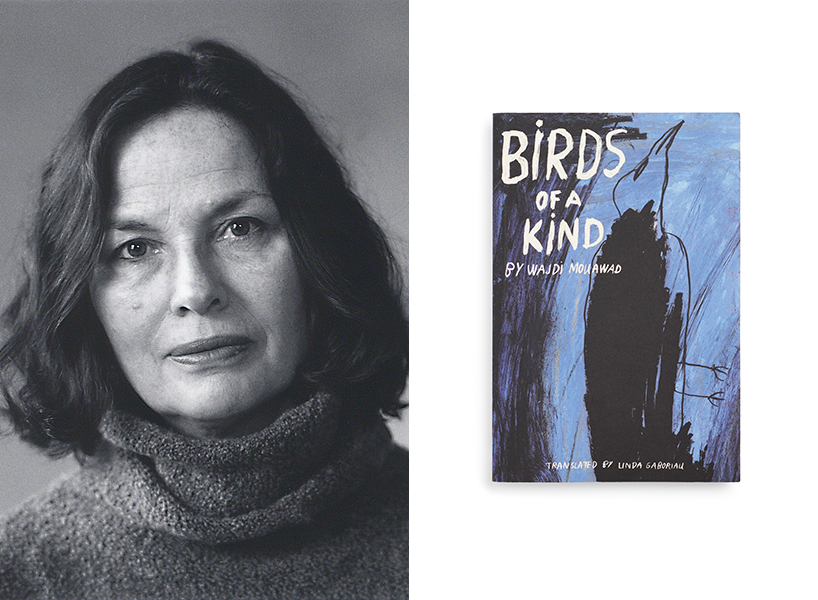

Translation – for Birds of a Kind, Linda Gaboriau

Linda Gaboriau is the award winner for translation, for Birds of a Kind, a work from Lebanese-Canadian playwright Wajdi Mouawad. An intense drama about identities—Gaboriau calls it “a Romeo and Juliet story”—Birds mostly unfolds within Israel after a terrorist attack puts a young Israeli-German genetic researcher in a coma, leaving his Moroccan girlfriend and his antagonistic parents to pick up the pieces of their lives. “The writers I aim to translate,” says Gaboriau, whose count she reckons now tops 125, with more than 100 being plays, “are those I consider in-depth witnesses to the issues of our times, whose testimonies I want to share with English-language readers. I have a particular affinity for Wajdi’s works—he’s a marvelous theatre artist—and his take on those issues. Here, without political commentary, he looks at the toll the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has taken on entire generations.”

Linda Gaboriau is the award winner for translation, for Birds of a Kind, a work from Lebanese-Canadian playwright Wajdi Mouawad. An intense drama about identities—Gaboriau calls it “a Romeo and Juliet story”—Birds mostly unfolds within Israel after a terrorist attack puts a young Israeli-German genetic researcher in a coma, leaving his Moroccan girlfriend and his antagonistic parents to pick up the pieces of their lives. “The writers I aim to translate,” says Gaboriau, whose count she reckons now tops 125, with more than 100 being plays, “are those I consider in-depth witnesses to the issues of our times, whose testimonies I want to share with English-language readers. I have a particular affinity for Wajdi’s works—he’s a marvelous theatre artist—and his take on those issues. Here, without political commentary, he looks at the toll the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has taken on entire generations.”

After arriving in Montreal from her native Boston to study French at McGill University in 1963, Gaboriau established her life and career in Canada. At 77, she is the oldest of the 2019 winners and one of the most eminent translators in Canada, having co-founded the Banff International Literary Translation Centre, North America’s only international residency for literary translators. The Centre now annually gives out the Linda Gaboriau Award to outstanding translators. “I came to this through cultural journalism in the 60s—rock ‘n’ roll included, if you can believe it,” adds the mother of rock star Melissa Auf der Maur—“and a lot of theatre criticism. Eventually someone asked me to translate a play. In the beginning I saw it primarily as bridging-the-solitudes work, though now it’s more the specific idea or the particular language and style that attracts me. Sometimes translation is just plain fascinating, like puzzle-solving or lace work—intricate and satisfying.” In 2010 the peer assessment committee also awarded Gaboriau the GGBooks prize for her translation of Mouawad’s Forests. Winning again this year for the same author may have surprised Gaboriau as much as it delighted her—“I kept asking them on the phone, ‘Are you sure? For the same writer?’”—but she is happy the “affinity” she feels with Mouawad is manifest to others, a recognition of “the interaction between writer and translator.”

This article has been written in partnership with the Canada Council for the Arts, which means the Council had editorial input into this piece.