How Rush lived, worked and rocked through the 1980s

‘Rush were celebrating everything it meant to be Canadian,’ writes Martin Popoff in ‘Limelight: Rush in the ’80s.’ Read this excerpt from the second volume of Popoff’s biography of the legendary band.

(l-r) Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee and Neil Peart backstage on Rush’s Permanent Waves tour (Fin Costello/Redferns/Getty Images)

Share

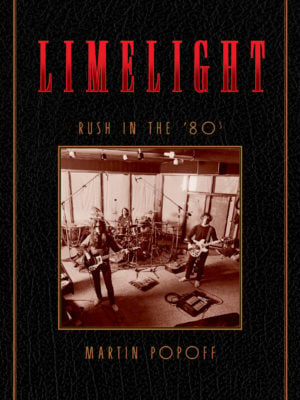

Fans of a certain legendary Canadian rock trio eagerly anticipated Martin Popoff’s latest biography. That band is Rush, and Popoff—who has penned dozens of books on hard rock, heavy metal, prog rock and punk—just published the second of a three-volume bio of the band. Limelight: Rush in the ’80s was released on Oct. 13, and it covers Rush’s iconic albums from that decade, Moving Pictures and Power Windows. Read this excerpt from the second chapter of the book.

Pleased with the living/working arrangements for A Farewell to Kings, Rush tried it again for Hemispheres. Pleased with the living/working arrangements for Permanent Waves, Rush tried it again for Moving Pictures. Fortunately, the sequel effort this time didn’t disappoint, and the guys found themselves more Canadian than ever. Living and raising families in Canada, writing on Canadian farms, recording immersed in the Canadian forest, bridging the divide between English Canada and French Canada, winning Junos and paddling canoes . . . Rush were celebrating everything it meant to be Canadian.

Pleased with the living/working arrangements for A Farewell to Kings, Rush tried it again for Hemispheres. Pleased with the living/working arrangements for Permanent Waves, Rush tried it again for Moving Pictures. Fortunately, the sequel effort this time didn’t disappoint, and the guys found themselves more Canadian than ever. Living and raising families in Canada, writing on Canadian farms, recording immersed in the Canadian forest, bridging the divide between English Canada and French Canada, winning Junos and paddling canoes . . . Rush were celebrating everything it meant to be Canadian.

“We went out to Ronnie Hawkins’s farm, out in the Stony Lake area,” begins Alex, on preparations for the record that would serve as Rush’s Machine Head and Paranoid, or Fragile and Not Fragile, as it were. “I guess it’s just north of Peterborough. He had a really nice little home up there, nice cottage with a big barn on it. We converted the barn into the studio, and set Neil’s drums up, and had areas for Geddy and myself. And it was a really nice location.

“We were there in the summer, and everybody was in good spirits. There was a good energy to the work. We started writing there and basically wrote everything in rehearsal there, and then moved into Le Studio later that fall and started recording. There was a real positive energy, not unlike what we went through with Snakes & Arrows years later. But at that time, there was just something that was very strong and positive about where we were with that record. I don’t want to say it was effortless, but the effort seemed to be very smooth. We had some guests visit, and we had a lot of fun across the whole process. It wasn’t just in the studio — it was a really nice place to be at that point in our lives.”

The guys were enthusiastic about carrying on the concept kicked off with the last album. “Yeah, it was great, really exciting,” Alex continues. “Because instead of one story you had five stories in the same time span, but you could link them with a sentiment or with an idea. A little bit less so with Permanent Waves but more so with Moving Pictures—that whole idea of a collection of short stories is what we were after and that’s what Moving Pictures is.”

Consensus is that Moving Pictures is the record where Geddy toned down his patented high shriek. “I bought it at Kresge’s,” laughs Lee on coming up with it in the first place. “I keep it downstairs in my studio for when I need it. Lifetime guarantee.

“I think I can still shriek if the music requires it,” figures Geddy. “I have no conceptual adverse feelings about it. As the music changed, it became more interesting for me to write melodies as opposed to shrieking. It was basically used for cutting through the density of the music. And sometimes we would write without any consideration for what key we were in in the early days, and I would find myself with twelve tracks recorded in a key that was real tough to sing in, so I didn’t have a choice at that point. Re-record the record in a different key or just go for it.

“Alex started getting really heavily into model airplanes,” says Geddy, offering further glimpses into Rush’s release valves during writing and recording. “It started when we were writing Permanent Waves, when we were at Lakewood Farms, in a little farmhouse out of the city. And even Terry Brown got into it. In fact, we had a lot of fun. In August of ’80, writing Moving Pictures, we were working on Ronnie Hawkins’s farm out near Stony Lake, and Alex was really into these remote control airplanes. He would spend hours building them. And of course, they would always go haywire, where they would get up too high, or lose control or something. And I remember, there was one that went completely haywire and ended up crashing and exploding on the top of Ronnie Hawkins’s truck, put a big hole in the top of it.

“And then Terry Brown had this fantastic giant one, this giant plane he had been working on. It was so big you had to have this kind of tether so it would fly around in circles. And it had a huge engine on it. And I remember he finally cranked it up and man, it took off! And suddenly, we all had to hit the deck! It was like this charge went out, and everybody is diving for the ground, and poor Broon is holding onto this thing going around in circles. He’s going around and around and around [laughs]. Finally the plane ran out of gas and landed, and he basically fell over in the grass. He was completely dizzy; it was hilarious.

“And we continued that at Morin Heights. Alex, and in fact, Tony Geranios, who is also known as Jack Secret, started working on rockets, and we would have these rocket launches, sometimes at dinner, sometimes at breakfast. I remember one time he launched one in the backyard, and the thing just took off the wrong way completely and missed exploding in Alex’s brand-new Mercedes by inches. It was always great fun. And Alex got into water planes at Morin Heights, because they had a lake. He would land it in the water and take off from the water.”

Notes Terry, on the way the band had been evolving at this juncture, “We went for a bigger sound. But then looking at the instrumentation, there were more keyboards. So the guitar needed to be textured differently. But then we used chorus for many, many years; this was not something new. It was just the way it was used. Alex was always into delays. I loved working with him for that reason. He had all these delays he would put through the amp, so we were always getting these great guitar sounds right through the amplifier—we weren’t adding delay afterwards. But yeah, the guitar sound changed, and it needed to change. The material was different. You can’t go back in and do the same thing every time. You’ve got to move forward.

“We were working forty-eight-tracks,” continues Terry, “and we would cut the drums and some guide guitar and bass parts on one twenty-four and put it away until we were finished, and then put a guide track on another twenty-four-track and then fill it up with all our overdubs. So we didn’t really approach it a lot differently than we had before, but there was some magic going on, certainly that day when we loaded in and set up the drum sounds for ‘Tom Sawyer,’ and it just blew everyone away. It was very, very exciting. It’s a hard thing to break down though. It’s a combination of the right time, the right place, the right song, the right parts and the energy that was around us at that time. But it definitely has a magic to it.”

Excerpted from “Limelight: Rush in the ’80s” by Martin Popoff. © by Martin Popoff. Published by ECW Press Ltd.