How the elevator changed everything

A book review of “Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator” by Andreas Bernard

Share

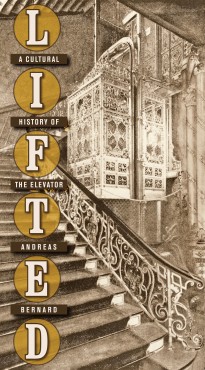

LIFTED: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE ELEVATOR

LIFTED: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE ELEVATOR

By Andreas Bernard

There are a lot of candidates for the inanimate icon of modernity—the one object to symbolize the sea change in Western life between about 1870 and the Depression—the car, the airplane, the machine gun, even the flush toilet. Bernard makes a compelling case for the elevator.

Before its widespread use, most buildings were capped at six or seven storeys, and their layouts varied widely between floors. Most striking, the wealthy once lived close to the ground, while the poor lived high, in starving-artist garrets. To metaphorically go down the social ladder was, literally, to ascend a building’s stairway: the struggling protagonist in Joseph Brod’s novel Hotel Savoy (1924), already reduced to the undesirable sixth floor of a provincial Polish hotel, wonders ironically, “How high can I fall?” The elevator reversed that pattern in the blink of a cultural eye, bringing the higher classes to the higher floors, to their now-defining penthouse suites.

Bernard, a German journalist, has plowed through an enormous number of architectural and engineering guides, novels, plays and newspaper articles for his utterly absorbing account of a device that changed the way cities looked and city dwellers lived—and sometimes died. Our own new technology (social media) may be disruptive and occasionally dangerous (distracted driving), but modernity’s founding inventions used to kill people at an alarming rate. Crashing elevators certainly took their toll in the early years, although they killed fewer people than falling into open shafts did, and both figures were smaller than the number of those who suffered smashed or even amputated limbs by sticking them out of open elevator cars.

More familiar to our own times, prone to worries over the health effects of wireless devices, were the anxieties and psychosomatic illness reported. The nausea and stomach-in-the-throat feeling brought about by still-abrupt downward stops—many early users only took elevators up, never down—gave rise to what one Chicago physician, worried over what he saw as resultant “brain fever and disordered nervous systems,” called “elevator sickness” in 1894.

Elevator social etiquette was disorienting, too. At first, as illustrated by the dialogue in William Dean Howells’s 1884 one-act play The Elevator, gentlemen would take off their hats when entering one, because it was not thought of as a public conveyance, but as a mobile domestic setting. And for good reason: In late 19th-century hotels, theatres and even some office buildings, cars were lavishly appointed, often with upholstered seating.

It took years for strangers haphazardly thrown together to learn to ignore one another and simply stare blankly at their floor numbers, a situation helped immeasurably in the past decade by the ability to pull out a smartphone to stare at instead. Perhaps, as Bernard implies, we’re still working out how to cope with the elevator.

Brian Bethune

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary.