In ‘Harry Potter and the Cursed Child,’ a beloved series gets a proper finale

The insanely popular wizardly tale comes to an end with a truly shape-shifting finale in a script that J.K Rowling didn’t directly pen

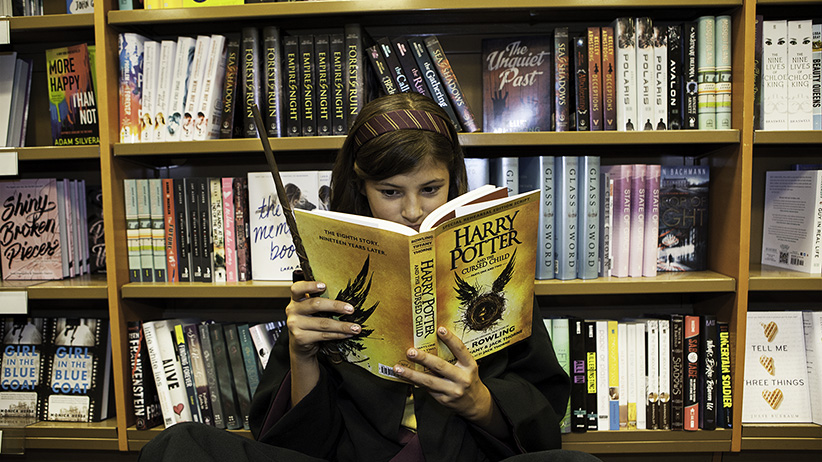

Amy Stocking reads from Harry Potter and The Cursed Child at the 12:01 launch of the book at Indigo (Bay and Bloor). Photograph by May Truong

Share

Harry Potter is back, nine years after J.K. Rowling released the last book in her seven-volume opus about a boy who defeats a malevolent wizard. Fans dressed up, then lined up to buy Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, Parts One and Two at midnight on the character’s 36th birthday.

It is an absorbing epic that deftly weaves together adventure, angst, laughter and life lessons with the series’ oft-repeated themes of love and choice at the heart of its magic. Above all, The Cursed Child is the ending to the series that fans deserve.

It doesn’t answer every question—some beloved characters aren’t included, some puzzles are left unsolved—but rather, unlike the abrupt epilogue at the end of the seventh book that taunted readers with “What if” queries for nine years, this feels like a proper finale.

Though Rowling’s name is prominently featured on the cover, she didn’t write a new novel. Instead, this book is actually the script to a new, critically acclaimed play in London, England. Rowling was intimately involved in the story and the play, but it was written by award-winning playwright Jack Thorne.

(Note: The next four paragraphs contain some early plot details.)

It starts innocently enough, where the epilogue ended, 19 years after Voldemort was vanquished at the Battle of Hogwarts, with Harry Potter sending his younger son, Albus, off to Hogwarts. Like Harry at his age, Albus is impetuous, kind-hearted and unhappy. He struggles to fit in.

On the train, Albus befriends Scorpius Malfoy, son of Draco, who tormented Harry during their school years. Both boys feel the burden of being the sons of famous men. “I didn’t choose to be his son,” complains Albus.

At the same time, a middle-aged Harry is stooped under the weight of the sacrifices made by those around him. “How many people have died for the Boy Who Lived?” says Amos Diggory, whose son, Cedric, was killed by Voldemort in an attack on Harry.

When Harry, head of Magical Law Enforcement, turns down Amos Diggory’s plea for a Time-Turner that could bring his son back, Albus and Scorpius decide to fix what they see as Harry’s mistake by helping Cedric’s grief-stricken father. Their quest to rewrite history upsets a delicate temporal balance, spawning a series of alternate realities that threaten to destroy all that Harry saved.

While the plot is quintessentially Harry Potter, the script format is a radically different medium for fans who are used to Rowling’s richly textured written world. As anyone who read Shakespeare in school knows, a script is a two-dimensional map to the whole artistic creation: the stage production. This script is no different, its emotional impact muted compared to the books. (In contrast, critics last month heaped superlatives into their reviews of the play.) Where the script matches the live performance in London is at its heart-rending climax. Tears poured down the cheeks of a silent audience in London’s Palace Theatre at the first preview performance.

In some ways, The Cursed Child’s script is a return to the first three books, shorter and tighter than the flaccid exposition in later instalments. The script format lets readers skip over Potter-esque flourishes, especially in the stage directions. When Albus and Scorpius use a Time-Turner, the script reads: “There is a giant whoosh of light and smash of noise. And time stops. And then it turns over, thinks a bit, and begins spooling backwards…” Or when Harry is jerked awake after a nightmare: “He waits a moment. Calming himself. And then he feels intense pain in his forehead. In his scar. Around him, Dark Magic moves.”

Though Rowling’s magical world will expand in November with the film release of Fantastic Beasts, set in the United States four decades before Potter’s era, the current stage production, and its script, marks the end for Harry Potter. At the two-part play premiere on July 30, Rowling told Reuters: “I’m thrilled to see it realized so beautifully but, no, Harry is done now.” If The Cursed Child is the finale of Harry Potter’s story, then Rowling has ended as she began, with a creation that is unexpectedly different and decidedly magical.