Inside the machinations and magic of pop music

A writer delves into the largely anonymous, fascinating machine that churns out today’s pop hits and tells their human stories

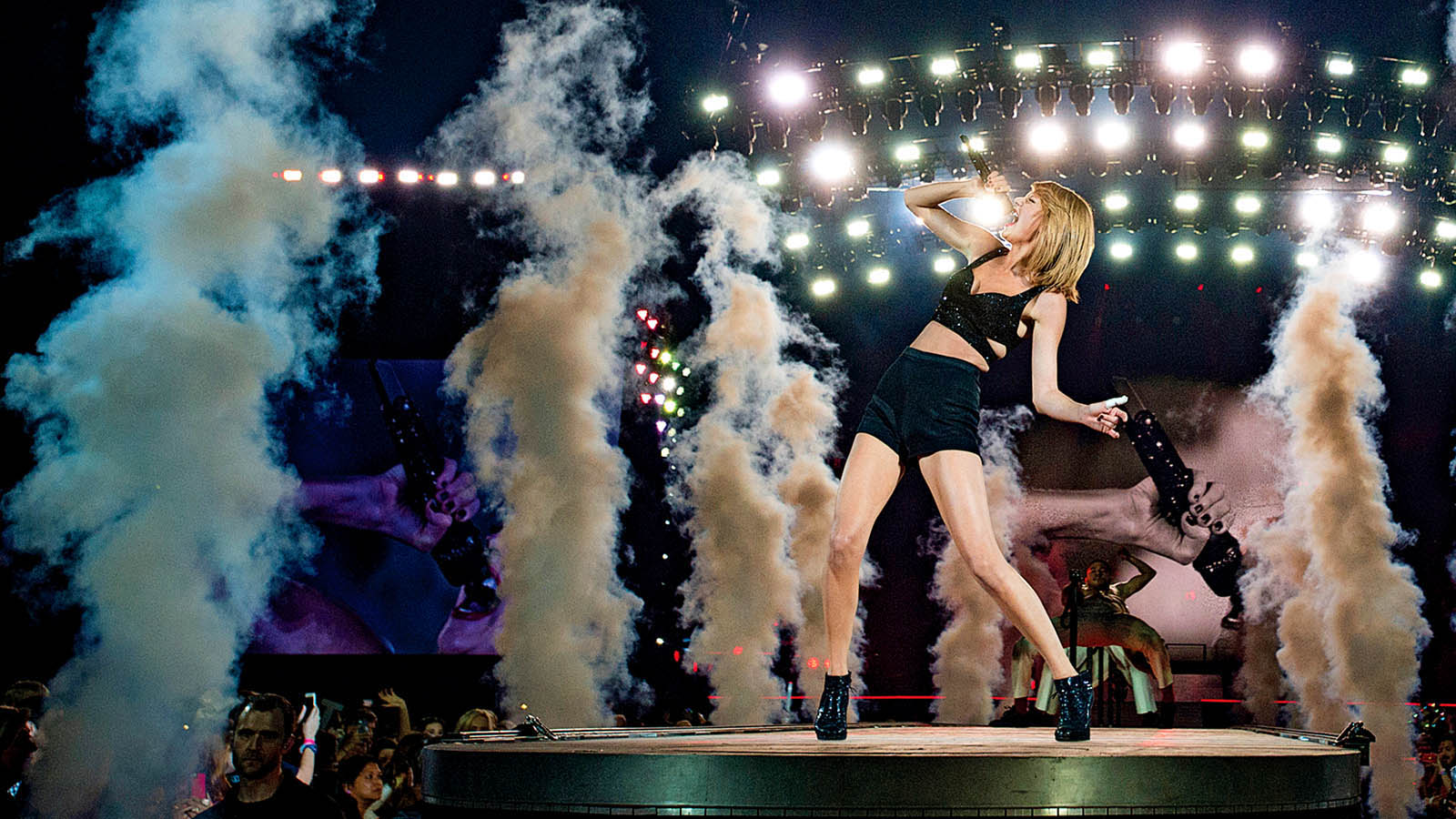

ARLINGTON, TX – OCTOBER 17: Taylor Swift performs onstage during the 1989 World Tour Live on October 17, 2015 at the AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas. (Cooper Neill/Getty Images)

Share

THE SONG MACHINE

John Seabrook

When it came out in September, perpetually weepy singer-songwriter Ryan Adams’s cover album of Taylor Swift’s candy-coloured, slickly produced 1989—last year’s biggest-selling record—became a battleground for an enduring cultural argument: Is popular music inherently schlock? Could this man, whose forlorn acoustic stylings practically sweat authenticity, redeem T-Swift’s pop artifice?

Of course, that line of thinking relies on the premise that pop music needs redeeming in the first place. Enter Seabrook, whose work at the New Yorker has showcased the minds and mechanics behind the chart-topping smashes that burrow into our brains. With The Song Machine, Seabrook—inspired by his son—fetes pop’s intoxicating thrill and sheds light on the cabal of mostly anonymous wunderkinds behind the curtain, pulling the strings of our emerald and wizardly stars.

There are the powerful producers, who deploy drum machines and computer programs to create a soundscape packed with gleaming hooks primed to turn listeners into addicts; there are the “topline” writers who craft the melody the pop star sings, which clicks just-so to fire a hit of adrenalin to the brain; and there are the lyric writers, who help pop stars—frequently depicted in this book as well-meaning vessels who succeed the more they obey the producer—craft their messages. It’s all stoked by the tyranny of what legendary music man Clive Davis calls “a continuity of hits”: To be a pop star, you need a lineage of big songs; hence, the churn.

It’s an industry of craft and cunning, of hopes and dreams, populated with people such as Denniz Pop, the doomed Swedish producer whose spacey guru vibe and brilliant instinct about pop hits—“sometimes you have to let art win,” he liked to say—let loose a clutch of fame-averse Nordic European producers who still quietly create most of our bestselling songs, from Max Martin to the duo Stargate. There’s Lee Soo-man, Korean pop’s kingmaker, who transformed the chart-hit assembly line into a factory farm, and Ester Dean, the masterful topline writer who can conjure massive smashes from nonsense words on her iPhone and has influenced hip hop’s biggest stars, though she can’t break through as a star herself.

So the book is a tonic for a too-common belief that pop is simplistic and formulaic. The humanity that fuels what Martin called “melodic math” just proves its vitality. And just because it’s manufactured doesn’t mean it’s artless, either; otherwise, we’d have to dismiss the industrial factory of Motown, the output from the Brill Building and, as one profiled producer noted, the works from the studios of the Renaissance’s masters.

It’s no coincidence The Song Machine winds down with an exploration of Spotify, the streaming service offering a new model for a crumbling music industry. After all, that argument over 1989 and its artistic merits is perhaps not as important as what the record says about the business: Taylor Swift’s original may have been 2014’s best-seller, but her first-week sales were roughly half of what they were when N’Sync topped the charts in 2000. As Pop said, you have to let art win—but only if it can survive.