This mid-century photographer captured the Inuit’s disappearing way of life

A new book chronicles the Canadian Arctic expeditions of photographer Richard Harrington, who visited the Canadian Arctic six times between 1948 and 1953

Share

On an assignment for the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1946, the photojournalist Richard Harrington travelled to a Chipewyan settlement near the northern Manitoba border. The German-born Canadian photographer, who died in 2005, self-financed five more expeditions to the Canadian Arctic between 1948 and 1953. Sled dogs hauled him to the shores of Hudson Bay and through much of present-day Nunavut, covering some 5,600 kilometres. He took countless black-and-white photos of snow structures and austere landscapes, hunters and smiling families, all in an effort to document the everyday lives of Inuit communities.

More than 100 of Harrington’s images appear in a new book, Richard Harrington: Arctic Photography 1948–53, which features a biography by gallery owner Stephen Bulger and a foreword by artist and curator Gerald McMaster, a Plains Cree citizen of the Siksika Nation. McMaster describes how Harrington’s photos of Indigenous people are less romanticized than those by other white photographers, who sometimes staged their subjects in headdresses or traditional attire. Harrington showed the inside of igloos, papered with magazine clippings; an Inuit man with a gun next to a seal he’d just shot; and a friendly game of tug-of-war. Still, Harrington was always an outsider: his Inuit hosts called him adderiorli, or “the man with the box.”

READ: This Winnipeg art gallery is a monument to Inuit culture

He is best remembered for his photos of the Padlei community in Kivalliq, a large region in southern Nunavut. In 1950, it was hit with a famine when the caribou, an essential source of food and raw materials, shifted their migration patterns. Many Inuit in the area died from starvation. By the end of the decade, the Canadian government ordered some survivors out of their camps and into outposts in the High Arctic. (Although the government claimed the relocation would be better for hunting, many Inuit believe Canada used their forced migration to establish claim to High Arctic land.)

Harrington’s searing images of Inuit communities show their perseverance as disease, government-mandated displacement and the south’s growing influence threatened to erode their culture. Here are some of his intimate glimpses of Inuit ways of life in the Arctic.

In this image, a mother “kisses”—or rubs noses with—her son in their igloo in Padlei. At the time, the community faced widespread starvation due to the 1950 caribou famine. The pair were later identified by the Toronto Star as Keenaq and her son Steven Keepseeyuk, who both survived the harrowing winter.

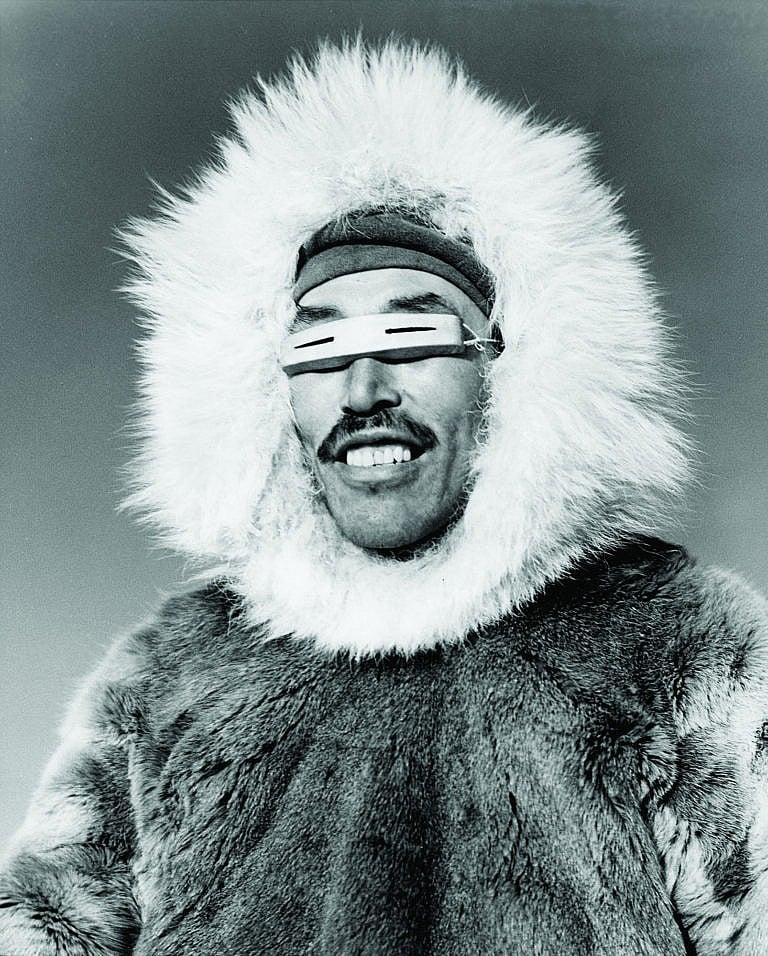

This Inuk man is wearing snow goggles, which were often made from a piece of bone or wood. Inuit developed them 2,000 years ago to protect against snow blindness; the thin slits keep out the glare of the sun reflecting on snow. “This could be fashion today,” says McMaster. “Snow goggles like these were essentially the first sunglasses.”

This Inuk child in Taloyoak, Nunavut—formerly Spence Bay, N.W.T.—has a puppy in her hood. McMaster notes that she’s likely imitating her mother; Inuit women wear a special parka called the amauti and carry their babies in a pouch below the hood to keep them warm.

In 1950s Kivalliq, traders still heavily depended on Inuit communities for their hunting skills. The hunter pictured here is likely displaying his yearly catch of Arctic fox, which he could exchange with the Hudson’s Bay Company for goods like guns, tobacco and tea.

Old magazine pages stuck easily to the wall of this igloo in the hamlet of Igloolik, N.W.T. (now Nunavut), in 1952. “The magazines might have been for decoration or insulation,” says McMaster. “But Inuit have also been looking at the outsider for hundreds of years.”

Oolie, a fisherman from Padlei, fishes through 150-centimetre-thick ice during the caribou famine. A snow-block shelter shields him from the wind. “Inuit fishermen would wait patiently for fish for hours—when the time is right, it’s right,” says McMaster.

People play a game of tug-of-war in Taloyoak. The man in the front wears watertight mukluks, likely made of sealskin and caribou hide. “Inuit games focus on the strength and agility required to survive in the environment,” says McMaster.

Henry Voisey, post manager of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Padlei outpost, uses a 40-foot dog whip made of seal hide. The Hudson’s Bay posts across Nunavut bought furs at low prices and sold marked-up goods, which some say kept customers in a cycle of debt.

This article appears in the December 2023 print issue of Maclean’s magazine. You can purchase the issue here, or become a Maclean’s subscriber here.