Iris Murdoch’s life in ravenous, compulsive letters

The collected correspondence of Iris Murdoch, the British novelist and philosopher, reveal a life of intellectual and sexual hunger

Letters from Iris Murdoch. Edited by Avirl Norner and Anne Rowe. No Credit.

Share

LIVING ON PAPER: LETTERS FROM IRIS MURDOCH

LIVING ON PAPER: LETTERS FROM IRIS MURDOCH

Edited by Avril Horner, Anne Rowe

“Letters should aspire to the condition of talk,” Murdoch, the British novelist and philosopher, at one point tells a reluctant correspondent, who is no doubt intimidated by her reputation for brilliance. “Say first thing that comes into head.” It’s seduction—subtle, unmistakable.

When you consider that Murdoch is writing a female student with whom she is engaged in an intimate relationship, and that she is at the same time in correspondence with a male pupil, with whom she’s also having a dangerous fling—“Yes, you are a wolf, and have sent me a very wolfish letter,” she writes him—you get a sense of the tangle of communications running through this book, just shy of 600 pages, all redolent of a woman whose intellectual appetites and hunger for experience were equally insatiable.

Intimate, learned, generous, stern and flirtatious, the letters trace the fine line dividing the good of empathy—which Murdoch demonstrates to uncanny degree—from the creepiness of voyeurism, a tendency to which she too often indulges. Living begins when she is 15, breathlessly describing a sea rescue in her native Ireland—“That was a great thrill”—and ends, heart-wrenchingly, with her struggling through Alzheimer’s to write a valued friend (“Please forgive my blanc pages, I mean just not the writing”).

In between is an epic, epistolary 20th-century adventure. Murdoch studied at pre-Second World War Oxford, where she was an active communist. Later, while working with refugees in postwar Europe, she met Jean-Paul Sartre and immersed herself in French literature. She overlapped with the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein at Cambridge, becoming a devotee, then taught at Oxford. She had many gender-agnostic affairs, lots of them unconsummated (though, as she puts it, “writing these letters is not a sexless activity either”).

And her novels. “Jesus God how I want to write,” she says, describing it as an irresistible impulse to objectify “the queer conflicts I find within myself and observe in the characters of others.” Living speaks to her enormous creative output; a new book seems to appear every second page, culminating, arguably, in The Sea, The Sea, winner of the 1978 Booker prize.

Murdoch rarely mentions her books, though one wonders at the role her correspondence played in the work (she could spend four hours a day on letters alone). It’s clear that writing was her compulsion, and of that we are beneficiaries: she is a master correspondent, in whose hands letters achieve something akin to—yet more sublime than—the “talk” to which she says they should aspire.

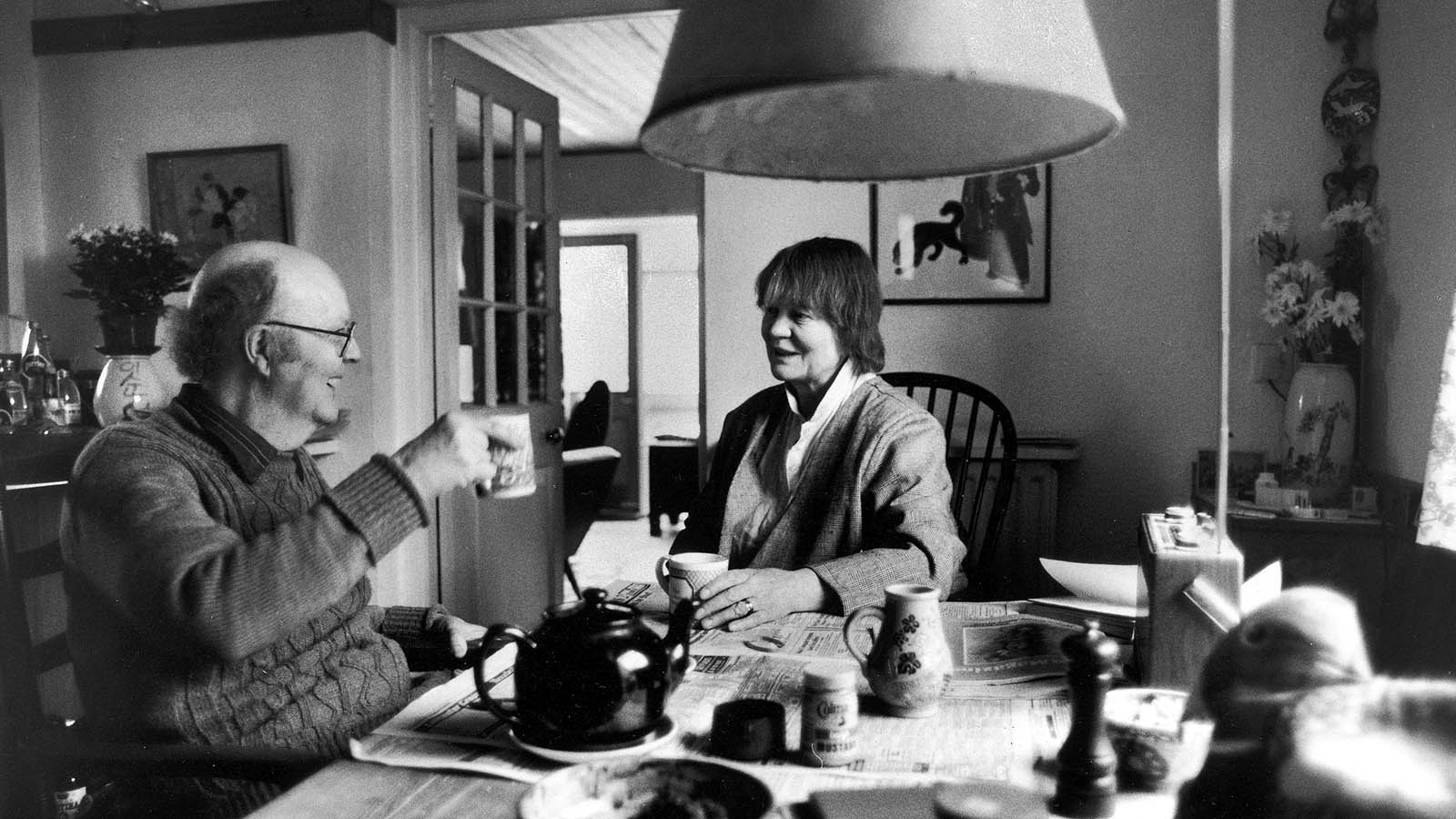

The high point of Living coincides with the height of her generative powers, in ’60s London, perhaps not coincidentally also the peak of her sexual intrigues. Her husband, John Bayley, who later cared for Murdoch in her dotage (heralded by a late-life conversion to Thatcherism), and whose own book formed the basis of the 2001 film Iris, was kept apprised of everything (“By the way, J knows about you, of course,” she tells one lover). Not one letter here is to him.