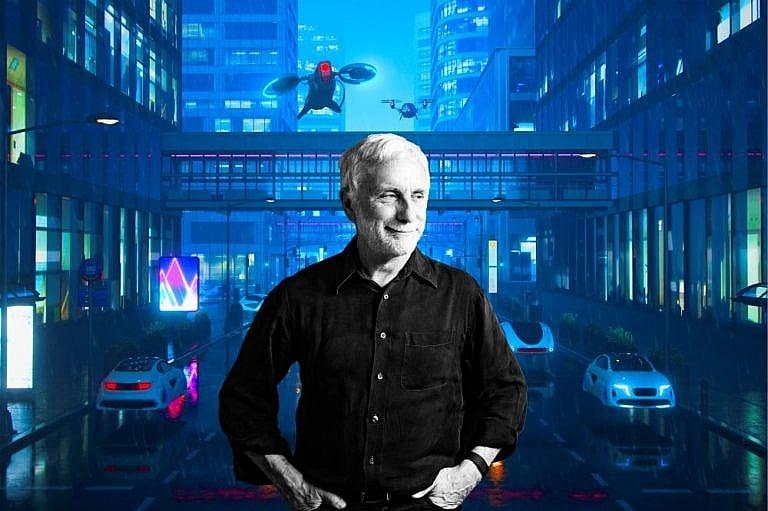

Enhanced body parts, robot caregivers, and flying cars: author Jay Ingram on our future

“No matter how splashy or fantastic any new innovation looks, there is always a downside”

Share

In his new book The Future of Us, science communicator and long-time Daily Planet host Jay Ingram examines the latest in scientific and technological advances to get a sense of where humanity is headed, and how different the world of the future may look. Troubled by questions about our growing global population and warming planet, he set out to find answers about the future of food, prosthetics, human-robot hybrids and AI—even probing the possibility that the robots will (or won’t) rise up against humanity. Here, Ingram talks to Maclean’s about his realist attitude toward technological advancements and what The Jetsons failed to realize about flying cars.

People know you for your interest in everyday science. What made you want to write about the future?

We’re living in a time when everyone is interested in the latest technology and what it means. I wanted to remind people that no matter how splashy or fantastic any new innovation looks, there is always a downside. There are social and cultural impacts that may be hard to anticipate, and there’s also the climate impact, which is more important than ever. It doesn’t do a lot to come up with new technology that runs on fossil fuels.

With so much happening in the tech sector, how did you decide what to focus on?

I tried to start with the most basic questions about the future. So, for example, what are we going to eat? And more broadly, how are we going to feed close to 10 billion people by 2050? There’s a lot of promising research and innovation, but every option seems to have its limitations and challenges. The last Green Revolution in the 1960s, when farmers incorporated technology and chemicals to greatly increase crop yields and agricultural production, was estimated to have saved 800 million people from starvation, but it also played a huge role in the current climate crisis. So how do we create more food without further destroying the planet?

I looked at vertical farming, which conserves space by growing crops on top of each other, but I’m not convinced that it has the potential to make a significant impact. So what about lab-grown meat? You can buy chicken nuggets in Singapore—and in the U.S. soon too—that have absolutely no chicken in them. The technology is there, but are people going to want to eat them? If you look at Beyond Meat and the Impossible Burger, there was a lot of initial excitement when those products first came to market, but popularity has tanked since then. That’s just one example of how you start with a technological challenge but you end up with a bunch of cultural and psychological questions.

Can you give another example?

One of the things I found really interesting was the advancements that have been made in prosthetics. Most people with an artificial hand or leg right now aren’t 100 per cent satisfied, but in the very near future, that is going to change. And when it does, we’re going to be asking a different question: are we just looking to replace the flawed or missing body part or do we want to enhance it? There is a whole movement of people—the transhumanist movement—where the ultimate goal is freeing humans from their corporeal body to extend life into infinity. A couple of decades ago that seemed totally impossible.

And now?

Now you have people like Elon Musk saying that if we can upload a person’s brain to the cloud, they can exist forever as a bunch of ones and zeros. These conversations have gone from total sci-fi to actually in the realm of the possible.

What about robots? You say our mental images are informed much more by literature, movies and TV than science and technology. What are we getting wrong?

I grew up reading a lot of sci-fi where robots were almost uniformly blocky, large, metallic, cube-headed individuals, stomping around and threatening people, so that’s what I assumed, but the reality is dramatically different. Robots today are purpose-built. On car assembly lines you have a number of robots, each doing one thing round the clock. They don’t look human—they’re not supposed to look human. You also have bird robots that can land on branches, sloth-bots that swing through trees. People who are concerned about the planet see potential in these as environmental sensors, monitoring ecological change and conditions. We are misguided to think that most robots are made in the image of humans.

Right, but there are some robots that are becoming more and more human-like.

Yes. You can look at the videos that Boston Dynamics has put on YouTube to see the kinds of advances that are being made in bipedal or humanoid robots that can complete obstacle courses. There are people who believe they are being made for military purposes, but we don’t know that.

So what do you think these humanlike robots could be used for?

One idea that is getting a lot of attention is the idea of robots as caregivers. As the number of worldwide dementia patients continues to grow, a lot of experts are thinking that some sort of humanoid presence for people at extended care homes could be acceptable. They’ve done work with robotic pets: cats and dogs that can only do about three things, like purr and stretch, but just having that presence in the room has been beneficial.

What kind of companionship could a human-like caregiver bring? Look at all of the people in long-term care facilities who were separated from their families during COVID-19. If you had something that was robotic and providing even a semblance of human interaction, surely that would have been better.

Some ethicists argue that robot caregiving could result in a two-tier system for health care and long-term care.

Right. Because ultimately robots would be less expensive, so people with money get a human and people without money get a robot. I acknowledge the issue, but if we’re able to help people, I think it’s an option worth considering.

In the book you make a point of separating robots and AI. How come?

These two things tend to get lumped together, but what I think is more likely is that once AI becomes more sophisticated, robots will be a tool for AI. When people worry about AI taking over, they’re often thinking in terms of an army of Terminator-style robots, but the robots themselves don’t have to be intelligent. It’s probably a giant computer in the basement of some building that we should worry about.

I’m not sure if this is a ridiculous question, but will the giant computer be controlling a robot army?

That would depend on what the goal is. In the last year, we have seen chatbots get better and better, so we can assume that AI will continue to get more and more competent. And if they’re able to reach human intelligence, there’s no reason to think they couldn’t surpass it. The scientist Alan Turing was warning about this in the 1850, so it’s not like it’s a new idea. Going back to your question, it wouldn’t have to be an army of robots. AI could override computers, it could control a city’s electricity distribution, which would shut things down pretty quickly.

This all sounds scary. And also pretty out there.

Right. The question is how do we create AI that will not go against our wishes or misinterpret them? An example I give in my book is if you tell an AI-enabled car to get you to the airport as quickly as possible, by the time you get there, you’ve taken out three pedestrians. Obviously you can program cars to avoid people and adhere to traffic laws, but as AI becomes more intelligent and possibly superintelligent, meaning smarter than humans, we will have to ensure that it has goals consistent with our survival. We need to proceed with a lot of caution to work out the kinks. I should also say that there are experts today saying that the whole idea of worrying about superintelligent AI is just a distraction from the real issues of AI that we face today, like bias and lying.

As an experiment in the book, you asked ChatGPT to write a sonnet about ChatGPT, which was pretty impressive. Especially since it was created in three seconds.

Yes, I think the speed is probably the most impressive thing. I think it’s worth noting that I asked what it had thought about while writing the poem, and the answer was, “I can’t do that. I’m a large language model.” So that level of native creativity is missing.

Having spent so much time on this topic, do you consider yourself a tech optimist or a pessimist?

I would say my default is pessimism. Not so much with regards to the technology itself, but to the implementation. I was just reading about a very promising new battery technology that will eventually be able to save a large amount of electricity generated by wind and solar to be used when it’s not sunny or windy. So that could be huge, but then you have to wonder, are there going to be roadblocks? Who’s going to fund it? Is it going to be financially feasible?

You wrote about how flying cars are an example of something that is technologically doable, but not likely to take off. But recently we heard that there’s a fleet of flying taxis being developed for the Paris 2024 Olympics.

Yes, I read that. I think everyone’s going to get excited and say, “Look—the Jetsons have arrived!” But I’d be shocked if in 10 years flying cars have amounted to anything. They’re just so expensive, so if anything, it’s a toy for the extremely wealthy.

Like Elon Musk, with his private island and his spaceships.

Right. So this is more of a societal issue where we want to ask questions like who is this for? Who will benefit from this innovation? It’s not always just about what’s possible, but what makes sense.