Joy Kogawa’s reflections on global and personal wounds

A Japanese-Canadian’s sombre memoir on a troubled past

Share

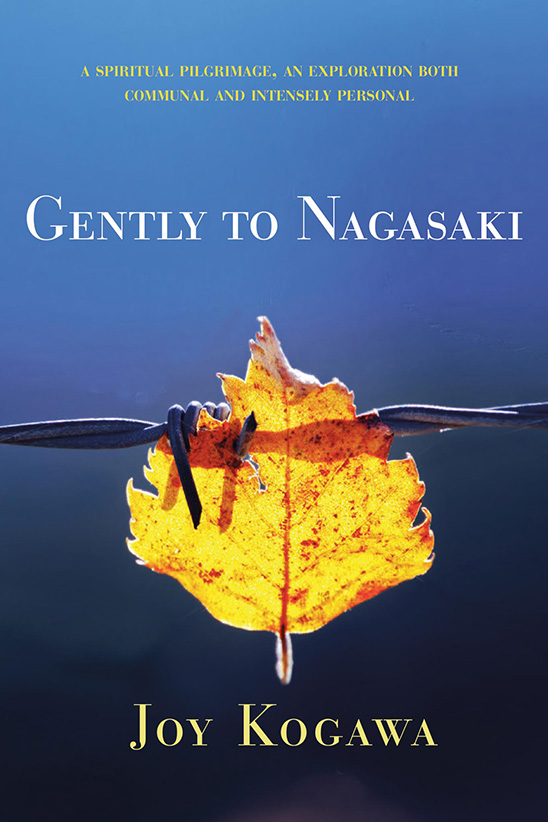

GENTLY TO NAGASAKI

By Joy Kogawa

Cerebral, deeply earnest and heavy-hearted, the 43 chapters of this book depict an unsettled Joy Kogawa meditating on the burdensome matters of her 81 years. Chief among them is the past. From the unparalleled atrocities of the 20th century (including the bombing of Nagasaki, the Nanking Massacre and the Holocaust) to Canada’s rabid anti-Japanese actions during the Second World War, her sombre memoir reflects a devout yet troubled person struggling with the evils of the world. Like many before her, the celebrated novelist (Obasan) agonizes over reconciling faith in a benevolent God with the brute facts of genocide, malice and immorality.

Kogawa also portrays her Vancouver-based family’s exile—“three years in a log cabin with cow-dung ceilings”—in B.C.’s mountainous Interior as well as the near-elimination of “an essential belongingness at the core of [her community’s] identity.” She touches on her undesired “shotgun wedding” in Alberta, bouts of mental instability following the subsequent divorce, public vilification, and her mother’s profound closing-off after internment and relocation to rural Alberta.

Looming above all these personal demons is a deep but conflicted love for her deceased father. An exceptional parent, devoted Anglican minister and thoughtful “Jekyll” (as Kogawa writes), his “Hyde”—a repentant and disgraced but active pederast—caused deep shame and lasting widespread aftershocks.

Despite identifying as a “recovered Christian fundamentalist,” Kogawa’s bone-deep religiosity suffuses her memoir’s pages. For any casual believer or atheist, the author’s reflexive piety (which manifests on the page through prayers, musings on Scripture, and addresses to a deity variously called the Forgiver, the One, the Knowing and the Infinite Light) will likely prove hard-going. Kogawa writes that she has long sought to heal the “wound in [her] Canadian heart.” Gently to Nagasaki ultimately offers a sobering treatise on the nature of some wounds: we can carry them with us long after their surface has healed and the pain they cause might never fully disappear.