Let this flower bloom: Mo Yan’s complicated vision of China

As a Nobel laureate from Beijing who isn’t a dissident, author Mo Yan is in a lonely club. His new book helps clarify things.

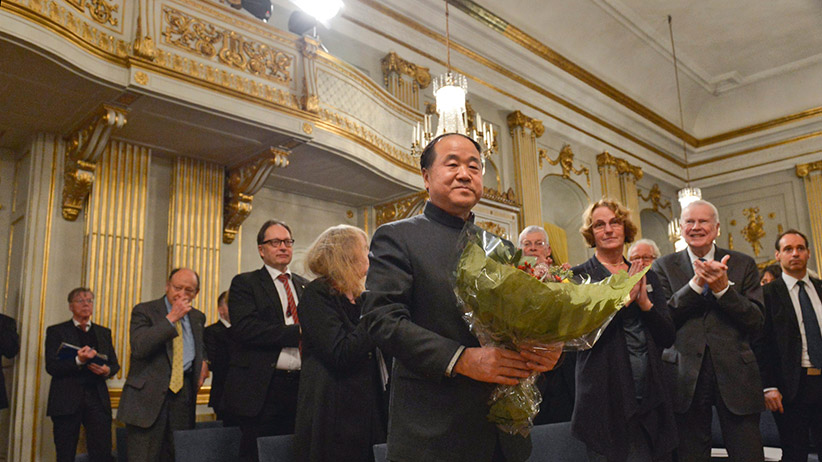

The 2012 Nobel Literature Prize laureate, Mo Yan of China is applauded from members of the Academy after his traditional Nobel lecture at the Royal Swedish Academy in Stockholm on December 7, 2012. Mo Yan is in Sweden to collect his award on December 10, 2012. AFP PHOTO / SCANPIX SWEDEN / JONAS EKSTROMER SWEDEN OUT (Photo credit should read JONAS EKSTROMER/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

Great artists speak most eloquently through their work. Certain ones should probably only communicate that way. The Chinese novelist Mo Yan, a writer whose pen name literally translates as “don’t speak,” is a great artist: original, daring and visionary. Off the page, he might want to follow his own advice more often.

Step back to 2012, when the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Mo Yan. For a Chinese Nobel laureate, the Beijing-based writer was unusual, being neither in exile, like 2000 winner Gao Xingjian, nor in prison, like Liu Xiaobo. The Chinese government denounced Liu’s citation, and refused to even acknowledge Gao, who had taken French citizenship. With Mo Yan’s, they were ecstatic, deciding it showed the world was okay with China’s resolute suppression of free speech.

Mo Yan, a member of the Communist party with a long record of participation in official —i.e. sanctioned—literary culture, made things worse by defending censorship in China at the Stockholm ceremony, comparing it to necessary airport security. He also initially refused to sign a petition for the release of Liu Xiaobo. His remarks triggered widespread international hostility. Salman Rushdie called him “craven” and a “patsy.” Others excoriated his apparent efforts at staying “free” in his fiction, and out of prison—or China—in his life, suggesting the two are incompatible. Easy for them to say.

Frog, Mo Yan’s first work to be translated into English since the Nobel, has been anticipated as much for what it might add to his uneasy stature in the West as for its literary value. Critics seeking further evidence for their case against the author will be disappointed. Admirers of his surreal, explosive, and quietly dissenting stories will be delighted.

Like all Mo Yan fiction, Frog hails from deep within the psyche of the eternal Chinese village. With their bawdy ways and violent habits, its raw northeastern peasants aren’t just a challenge to Western eyes and ears; the urbanites of Shanghai and Beijing may find them no less an assault. Meet Gugu, a midwife working out of Gaomi township in Guangdong province, the setting for most of Mo Yan’s books. Back in the late 1950s, Gugu was a teenage crusader, denouncing traditional midwifery. Into the 1960s, she delivered babies regardless of societal mood swings, serving her ancient nation’s core drive to be bountiful, to outmatch death with life.

Then comes arguably the biggest social engineering distortion of all: the one-child policy, introduced in 1978. Tarnished by a fiancé, Gugu careens from being a saviour of newborns to a zealous abortionist. She storms the county terminating unlicensed pregnancies, sometimes catastrophically, and sterilizing women. “China’s greatest contribution to humanity,” she calls the policy.

Her nephew, Tadpole, unfolds her rise and fall. An aspiring writer, he narrates most of Frog through letters to an unnamed Japanese correspondent. He reports mayhem and madness: starving children eating coal, and hysterical Cultural Revolution struggle sessions. He includes an unproduced play, dated to 2009, titled Frog: A Play in 9 Acts. It stars “Guyu, a retired obstetrician.”

Even the upheavals and disastrous politics of 20th-century China, Mo Yan insinuates, wind up as little more than private, possibly unsent letters and an unproduced play. And regular folk, those lowly amphibians of the title, absorbed more than their share of the misery. Nor has 21st-century affluence changed much—only the rich can afford the penalties that accompany insistence on a second or third child.

True to Mo Yan’s complex vision of his nation, Frog disavows binaries of right or wrong, oppressor or oppressed. It’s true as well to his penchant for sprawling casts and chaotic storytelling—often compared, curiously enough, to Rushdie’s phantasmagorias. Western and Chinese readers alike may struggle with Frog. But the sophisticates of Shanghai or Beijing will almost certainly recognize Gugu and Tadpole from any family ancestry portrait—or the mirror. Gaomi township isn’t a microcosm of the world’s oldest continuous society; it is a palimpsest. The eternal Chinese village endures.