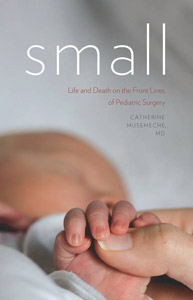

Life and Death on the Front Lines of Pediatric Surgery

Small offers a hair-raising account of the state of pediatric surgery

Small. Life and Dealth on the Front Lines of Pediatric Surgery by Catherine Musemeche, MD

Share

SMALL: LIFE AND DEATH ON THE FRONT LINES OF PEDIATRIC SURGERY

By Catherine Musemeche

Operating on infants is not as simple as learning how to sew in miniature, explains Musemeche in this fascinating, often hair-raising account of the state of pediatric surgery.

Musemeche has been working in the field for three decades and writes with the kind of drama that feels as visceral as viewing a documentary. Be warned that some of the passages aren’t for the faint of heart.

Babies aren’t just small adults: they’re fragile in complicated ways, she writes. Their paper-thin skin loses heat rapidly, requiring surgeons to operate in rooms that feel like cauldrons at 80° Fahrenheit. Infants born eight weeks premature are the size of kittens with organs like Jell-O that barely hold together. Often surgeons are operating by the seat of their pants. “We patch what can be salvaged, taking out dead and malformed pieces. When we are short of parts, we rearrange and make do. Then we sew it all back together with a needle the size of an eyelash.”

In pediatrics, the correct positioning of a breathing tube is measured in millimetres. Musemeche recalls a critical moment during her training when the breathing tube on a baby boy slipped down too far. Within seconds, his oxygen level dropped and his heart rate slowed. The anaesthesiologist disconnected the ventilator and started bagging the baby by hand to inflate his lungs, but in a panic to correct the problem used too much force. “The pressure blew out both lungs like they were dime-store balloons,” writes Musemeche in her adrenalin-producing style. She and her colleague started CPR using two fingers—the weight of a hand would’ve compressed the newborn’s heart. “We incised both sides of the chest with our scalpels and slid small drainage tubes between ribs as thin and pliable as Q-tips.” Air drained from the boy’s chest cavity and his lungs re-expanded.

Today, vast improvements have been made thanks to innovators like Canadian-born James Fischer, a surgeon who invented a better way to keep intestines alive when a child is born with the contents of their abdomen on the outside. His Bentec bag is now used in every major hospital in North America. “The days when pediatric surgeons had to operate with one hand tied behind their backs struggling with adult-sized instruments are coming to a close,” writes Musemeche. Now there are cameras small enough to see inside salivary gland ducts, and biopsy tools as tiny as a speck of dust. What remains the same is the skill, and mental fortitude, required of the surgeons.