‘Finally, proof that 12 years of psychoanalysis paid off for someone’

A review of ‘Little Failure: A Memoir’

Share

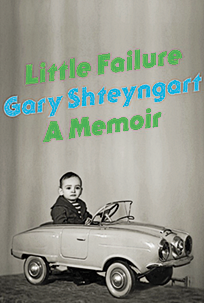

Little Failure: A Memoir

Little Failure: A Memoir

By Gary Shteyngart

Finally, proof that 12 years of psychoanalysis paid off for someone—and not just anyone, but Gary Shteyngart, a Russian-American writer who documents his coming-of-age experience in his first memoir, Little Failure. Shteyngart takes us along on his hilarious and painful transition from childhood comrade in Leningrad in the 1970s to foreign misfit in Queens, New York, where American Jews try to integrate these newcomers into the pack. “We Soviet Jews were simply invited to the wrong party. And then we were too frightened to leave. Because we didn’t know who we were,” Shteyngart notes, before officially stating the purpose of his memoir: “In this book, I’m trying to say who we were.” And boy, does he, by exploring childhood memories and dissecting the strange style of violent smothering called parenting in the Shteyngart home. The book is rich with one-liners and aches with the author’s desire to belong—buck teeth, and all. We hear his early reaction to The Brady Bunch (“What is the origin of their white slave, Alice?”), his translation of Russian swearing (“Go to the dick”), his take on his high school for gifted kids (“a holding pen for multinational nerds”) and see his unlikely devolution into a party animal—not a lawyer—at college. Oh, and he was a young Republican who had a subscription to the National Review and an NRA membership card. We all have skeletons.

Anyone who has read Shteyngart’s novels and magazine articles won’t find this memoir full of new material, exactly, but they will find new depth, with a better understanding of Shteyngart’s father’s complicated jealousy and love for his son. “I read on the Russian Internet that you and your novels will soon be forgotten,” announces his father. Oy.

The big surprise is his mother’s girlish charm. We’re told she often starts her stories, “Hey guys, want to laugh?” Yes, Shteyngart wants to laugh, and he makes us laugh, too, while explaining how this asthmatic Soviet Jewish transplant became who he is: “not a loner, exactly. But someone who can be alone.”

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary.