Moby’s from rags to raves to riches story

Moby’s autobiography is endearing, poignant and laugh-out-loud hilarious

Share

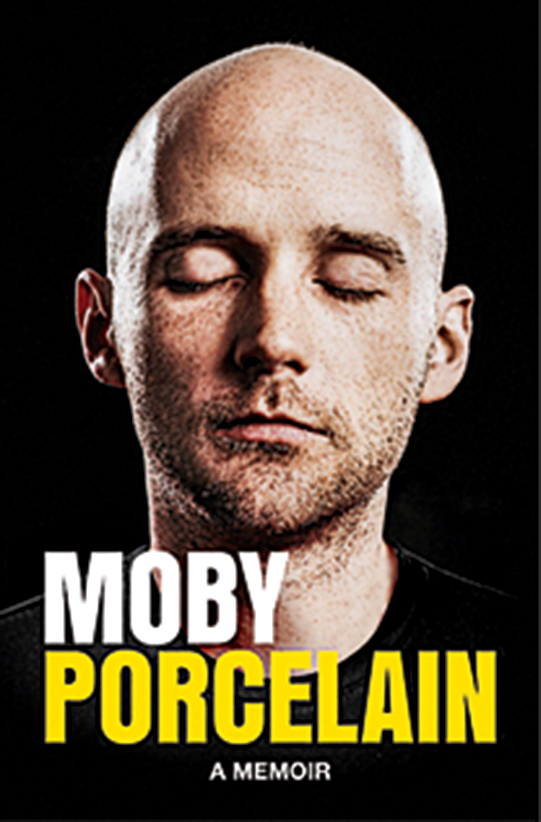

PORCELAIN

By Moby

Moby is a big Mötley Crüe fan. You’d never guess that, if you know anything about the electronic musician who was a teetotalling Christian when the early ’90s rave scene exploded. But at several points in his highly entertaining memoir—which is filled with misadventures involving awkward sex, booze, bodily fluids and weird celebrity encounters—he mentions the Crüe’s Shout at the Devil as a go-to private party record, and Porcelain reads as kind of a sad geek version of Mötley Crüe’s 2001 memoir, The Dirt (to which he nods in the afterword).

Moby knows he was never cool. Sure, his 1999 gospel-tinged electronic album Play sold millions of copies. (You will recognize it from every restaurant meal you had at the turn of the millennium.) But just prior to that, he’d bottomed out with panic attacks and an alcoholic relapse, and a detour into punk that almost killed his career. Though his story ends with riches, he never forgets the rags he wore as the child of a single mother surviving on food stamps in a Connecticut town full of waterfront mansions. That impostor syndrome fuels his withering self-deprecation. It’s what makes Porcelain endearing, poignant and laugh-out-loud hilarious.

The book’s 10-year narrative opens in 1989: Moby is squatting in a plywood-walled corner of an abandoned factory in his hometown. He dreams of being a DJ in the bright lights of nearby New York, a city teeming with garbage and crackheads, with hip-hop stars and house music pioneers and club kids who hold raves on subway cars. He soon gets a weekly gig at a hot NYC club, straps his record crates to a skateboard and hauls it through puddles of blood on the streets of the Meatpacking District. To his own surprise, he soon carves out an international career where every live gig is described identically: “I jumped around, banged on my Octapad, yelled ‘Go!’ a whole bunch of times, broke a microphone, and ended the show standing on my keyboard.”

You don’t need to know or even like Moby’s music to appreciate the absurdity and wit that drives Porcelain. He’s not interested in seeming likeable; he’s a self-described “balding vegan crying in a health-food store.” But he writes beautifully about the death of his long-suffering mother, the professional rejections, how he considered abandoning music altogether, how he tired of empty sex and endless hangovers. The ending is almost too perfect: he takes a this-is-your-life drive out of his beloved New York, back through his hometown, while listening to Play for the first time. He doesn’t bother telling us it went on to sell 12 million copies, or even that he finally found a record company to put it out—because that’s not nearly as interesting as how he got there.