Moving the needle: The past and the politics of vaccination

A review of Eula Biss’s ‘On Immunity,’ which tackles the history of anti-vaccination movements

A young child is vaccinated against the H1N1 virus in Schiedam November 23, 2009. (Jerry Lampen/REUTERS)

Share

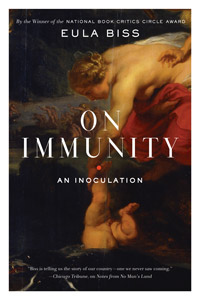

Eula Biss

With measles outbreaks in the headlines and Jenny McCarthy as poster girl, the anti-vaccination movement seems a very contemporary phenomenon. But, as Eula Biss explains in her superb new cultural history of illness and immunization, vaccines sparked epidemics of fear and loathing, even before they became an integral tool for public health. Take the term “conscientious objector,” now associated with anti-war activists: It was coined in the Victorian era by vaccine resisters. The key word, Biss notes, is “conscientious.” For the anti-vax masses, refusal is a matter of conscience, but she sees it as a case of caring so much that it obscures the big picture.

Such etymological detours come naturally to Biss, a National Book Critics Circle Award winner who approaches contentious scientific material with a poet’s eye and ear. Like Susan Sontag, whose Illness as Metaphor is frequently referenced in this text, she’s interested in the way we speak about epidemiological phenomena, and how it shapes our understanding of diseases, and of ourselves.

She uses her personal story as a framework. The daughter of a doctor, Biss found herself paralyzed by paranoia and indecision when it came to immunizing her own son. Her efforts to grasp the risks and benefits of vaccination ground this engrossing narrative, allowing her to explore and sensitively debunk the anxieties of anti-vaccination advocates. But On Immunity is not a lightweight personal riff. Biss’s research is extensive and enlightening. She investigates links between vaccines and autism (spoiler alert: there’s no proven causal relationship), and pores over arcane accounts of smallpox inoculation involving cow pus and open wounds. She describes how, in 2012, a Pakistani Taliban leader banned polio vaccinations, claiming they were “a form of American espionage.” That crackpot theory turned out to have credence. “In pursuit of Osama bin Laden, the CIA had used a fake vaccination campaign . . . to gather DNA evidence to help verify bin Laden’s location.” (The attempt failed.) The politics of immunization, it’s clear, are complex.

In the end, Biss arrives at an effective metaphor for immunity: “Our bodies are not war machines that attack everything foreign and unfamiliar . . . but gardens where, under the right conditions, we live in balance with many other organisms.” Anti-vaxxers, she notes, have prioritized the protection of their own environments over the fitness of others. With bureaucratic hurdles delaying Ebola treatments, this book seems especially timely. But the scope of Biss’s argument and the grace of her prose make it timeless.