Must-read books for June: Play to prose, restaurant reflections

Plus the memoir of a bold female restaurateur, and a new set of interlacing stories from Elizabeth Strout

June Books review

Share

This month in book reviews: The importance of a good team (and proper lighting!) in restaurants. Anything is possible, with a catch. The strange, melancholic, wondrous, wandering prose of Haruki Murakami. Read more below and check out the rest of our book reviews.

NEW BOY

NEW BOY

By Tracy Chevalier

HOUSE OF NAMES

By Colm Tóibín

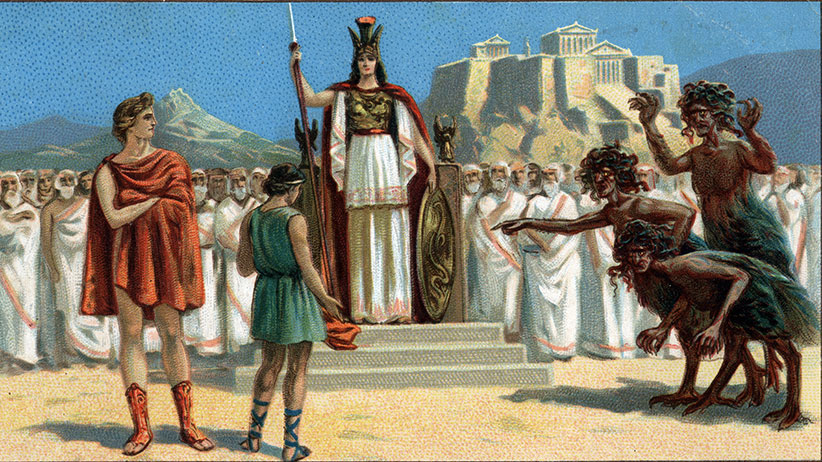

Reimagining stories, not just in different versions but in different genres, is hardly new. Book-to-film has always been the lifeblood of Hollywood, and Shakespeare’s dramas have inspired everything from operas to graphic novels. The play-to-novel transfer is undergoing a particular moment in the cultural sun, primarily because of the Hogarth Shakespeare series, which features prominent novelists retelling the Bard’s works in modern dress.

But it’s not entirely Shakespeare: this month sees the release of both the fifth Hogarth entry, New Boy—Tracy Chevalier’s take on Othello—and Colm Tóibín’s House of Names, the Irish novelist’s distillation of Greek dramatist Aeschylus’s 2,400-year-old Oresteia, a three-play cycle depicting the tragedy of the House of Atreus. The writers’ approaches—and success—couldn’t be more different. Chevalier moves her story almost four centuries in calendar time and, more crucially, a generation in psychological terms, while abiding by her original’s outline. Tóibín’s setting invokes Aeschylus’s, but his plot and characters are not entirely the same. New Boy’s reach exceeds its grasp, but House of Names is both contemporary and as primally disturbing as the Oresteia.

Like all modern readings of Othello, Chevalier’s stresses not just the personal—Iago’s malignancy and what the first Shakespearean critics considered Othello’s noble but hot-blooded nature (itself a racist trope)—but also the social. New Boy takes place around 1970, after major civil rights advances but before school busing, when Osei, an African diplomat’s son, is the first black child to attend his suburban Washington school. The other children, although they echo their elders’ casual racism, are existential in their reactions. Osei is, above all else, new and for that reason alone attracts (Dee, the Desdemona character) and repels (Ian, the novel’s Iago).

Structurally, the novel is a marvel. Its five parts mimic Shakespeare’s five acts, while Ian’s sly manipulations smartly recall the original’s plotline, with Osei’s strawberry-embossed pencil box standing in for Othello’s strawberry-embroidered handkerchief. But despite New Boy’s horrendous outcome, the mash-up of pre-adolescent emotional drama and classic tragedy ultimately fails to convince. When Ian, at last exposed, refuses to explain his actions, his “I have nothing more to say” falls flatly—a sullen 11-year-old’s declaration of mutiny, a far cry from Iago’s terrifying encapsulation of human nihilism: “Demand me nothing. What you know, you know. From this time forth I never will speak word.” And Chevalier’s hint that Ian may well get away with it—because adults do not take children seriously—simultaneously adds another, child-centred, theme to her novel and undermines its retelling of the original. There is no place inherently impossible for a Shakespearean drama to unfold—Hamlet has been set everywhere from crumbling Victorian mansions to modern prisons—but Chevalier’s generation gap is a stretch too far.

The story Tóibín tells—the human sacrifice of a daughter by her father, the revenge killing of her husband by his wife; the murder of the mother by their son; the torment then inflicted upon him by the avenging Furies—is so familiar, it is some time before readers note how free of detail his version is. The gods and the war that brought all that followed, the woman whose beauty prompted the conflict, the land, the sea around it—all go unnamed in Tóibín’s ironically titled novel. It is, in fact, a story about the annihilation of memory, and hence of human existence.

Tóibín’s enduring themes have always included the chaos and impermanence of life, and the eternal divide between those who think humans do what they do by their free will and those who don’t. Clytemnestra, the mother, abandons all thoughts of gods and duty, and she will kill her husband because she wishes to and because she can. Electra, the surviving daughter, will bend her brother Orestes to avenge her father. The two women have interior lives and tell their stories in the first person, yet Tóibín narrates Orestes—torn in two by the conflicting demands of paternal vengeance and honouring his mother—in the third person. He is a blank slate, uncertain of his duty or whether he can choose not to follow it, so manipulated by others that he becomes “a man capable of anything.” And by the time Clytemnestra’s ghost lurches into a brief “life,” already unable to remember the names of those she loved, Tóibín is asking if anything could have unfolded differently and whether any of it matters.

—Brian Bethune

I HEAR SHE’S A REAL BITCH

I HEAR SHE’S A REAL BITCH

By Jen Agg

Jen Agg has no tolerance for servers with “octopus hands,” the awkward habit of clutching drink glasses around the rim from above (where lips go), instead of down near the base (to prevent spills and contamination). “Who knows where your grubby little fingers have been?” the legendary Toronto restaurateur writes in her deliciously revealing memoir. “I know where mine have been (basically, if it’s a hole, I’ve been poking around there in the recent past) . . . ”

The anecdote is classic Agg, one that encapsulates: a) the hawk-eyed attention to detail behind her business success (it wasn’t just luck); b) her propensity to pontificate on icky truths (be it finger goop or the bro-chef kitchen culture); and c) a refreshing shamelessness about female sexuality (because even though she’s probably referring to belly buttons and earlobes in this instance, the mind does wander given how proudly she celebrates her sex life as “f–king awesome.”)

Agg has been pushing buttons with her shouty opinions ever since a fateful Saturday night in 2011 when, fed up with ill-behaved customers at The Black Hoof, her first restaurant in a current group of five (including the recently opened Grey Gardens in Toronto’s Kensington Market), she infamously tweeted: “Dear (almost) everyone in here right now. Please, please stop being such a douche.”

The tweet, which went viral and ultimately led her to this platform for talking about the hurdles of being a female leader in a male-dominated industry, doesn’t come up until page 255. By then, most reasonable human beings will concede her very valid points: servers obviously deserve to be treated with respect, and her restaurants aren’t for everyone.

Why should they be? The outdated assumption that the customer is always right is a notion as prone to abuse as the ridiculous, military-style hierarchy that still rules most professional kitchens.

With equal parts feminist swagger and den-mother softness, Agg’s compellingly conversational writing breaks new ground in the (typically macho) canon of restaurant memoirs by exploring the often-dysfunctional relationship between the front and the back of the house. A great restaurant is so much more than the sum of its food.

Even though she dwells for too long on a former partnership that went sour (bending over backwards to be fair about a breakup that is really only interesting to a small subset of Toronto-foodie gossips), Agg does make a passionate case for the importance of building a happy, well-functioning team—and, perfectionist to the core, the highly underrated power of good lighting.

—Alexandra Gill

ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE

ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE

By Elizabeth Strout

Wrenching yet delectable, the arresting tableaux and complex architecture of the nine interlacing stories in Elizabeth Strout’s second story collection (the celebrated Olive Kitteridge was her first) linger long in the mind. As master-class illustrations of causes and effects, they’re mesmerizing.

Although Strout has chosen the hopeful title Anything Is Possible, there’s a catch; a momentous one. Possible does not mean likely, not even close. Consider “Gift,” which ends with “Anything was possible for anyone.” On a stretcher, 65-year-old Abel Blaine of Littleton, Ill., has that joyous realization during what might be his second and terminal heart attack. Minutes earlier, he’d been inside a theatre dressing room, where a despairing actor (in Scrooge makeup but sans wig) held Abel hostage in order to unburden himself with a disillusioned autobiographical tale about a man “born queer” who’d mistakenly imagined theatre would nourish him. Listening in a cold sweat, Abel comes to understand that, despite success and family, for years he’d been profoundly lonely and stuck in a routine of exceeding emptiness.

In “Dottie’s Bed & Breakfast,” Abel’s estranged sister recalls “moments of human sadness” she’d seen in her guests’ eyes. For the judgmental breakfasting couple, though, she “spit in the jam and mixed it up and spit again, as much as she could gather in her mouth, and took some pleasure in seeing the jam bowl empty” when she was clearing their plates. In settings dominated by flat crop fields, Strout depicts shame, poverty, and whole lifetimes misshapen by compromises and errors. Or by wounds that never quite heal. Even the titular narrator of Strout’s last novel, My Name is Lucy Barton (who exists in the minds of Possible’s characters as an emblem of overcoming the odds) reveals herself, in “Sister,” as irreparably damaged.

For every sentiment echoing that of the title—such as “Happiness thrummed through her—she could eat it like bread!”—Strout recounts long years where “ghastliness descended.” Or encounters like that between a guidance counsellor, struggling with the fallout of a traumatic adolescent sexual experience and antidepressant weight gain, and a troubled student, which comes to a head with the seething woman saying, “Get out of here now, you piece of filth.”

—Brett Josef Grubisic

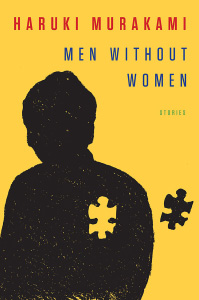

MEN WITHOUT WOMEN

MEN WITHOUT WOMEN

By Haruki Murakami

The Japanese author’s prolific and beguiling output has garnered an obsessive fan base, repeated whispers of an imminent Nobel Prize, and one of the most shoplifted oeuvres in literature. Murakami’s most recent book, Men Without Women, his first short story collection in more than 10 years, treads the familiar territory and themes of his previous work—melancholia and aloneness, a pervasive sense of the unknowable and mysterious. These elements of human existence are tempered with small moments of humour and surrealism and, in one story, treated with transcendent grace.

The collection is just seven tales, each containing a handful of characters—mostly pairs. The first, “Drive My Car,” features an older male actor and his female chauffeur; their daily commute acts as a kind of confessional box on wheels, especially when the subject turns to the actor’s unfaithful late wife. The title is a nod to the Beatles, one of Murakami’s frequent inspirations, and there are many musical references throughout the collection. In “Drive My Car” there is an apt bit of dialogue that plays to the theme of the story and of the collection—human blind spots. “…(T)he proposition that we can look into another person’s heart with perfect clarity strikes me as a fool’s game,” Murakami writes. “I don’t care how well we think we understand them, or how much we love them. All it can do is cause us pain. Examining your own heart, however, is another matter.”

That could be a trite, sentimental aphorism if it weren’t for the author’s skill in evoking the sadness and absurdity of life (other turns of phrase in the book are similarly borderline, and there are some clunky similes). The characters remain in the dark, lonely. Lives are scripted as beautiful riddles, people appear and disappear, and the reasons for human action are similarly evanescent. In stories such as “Yesterday,” “Scheherazade” and “Samsa in Love” (a twisting of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis) also possess a sweet, quirky tenderness.

However, “Kino,” the fifth story in the collection, goes far beyond the others. It is absolutely stunning: strange, melancholic, wondrous, wandering. Contained in it are all the reasons Murakami is held in such esteem.

—Erin Beth Langille