New York folk, from Gaslight Café to Village Gate

Book review: How New York’s Washington Square Park became the epicentre of folk music’s renaissance

Share

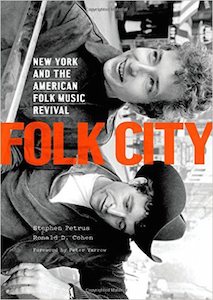

FOLK CITY: NEW YORK AND THE AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL

FOLK CITY: NEW YORK AND THE AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL

Stephen Petrus & Ronald D. Cohen

Fourteen years ago, author David Hajdu crafted a superb, perhaps definitive, portrait of Greenwich Village at the height of the folk-music revival of the 1950s and ’60s. But Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street focused on just four artists: seminal figures Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, along with supporting players Mimi Fariña (Baez’s sister) and her husband, Richard. Folk City, the companion to a multimedia exhibit now on display at the Museum of the City of New York, lacks Hajdu’s poetic legerdemain, yet, in its winningly plain-spoken way, provides a far more comprehensive appreciation of one of the most colourful chapters in American music.

The story begins in the 1930s, when the radical likes of Josh White, Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie converged in New York. It was the height of the Great Depression, a fertile time for such influential artists to “[redefine] the genre of folk music from a quaint musical form associated with rural life to ‘the people’s music’—a weapon of ideological battle to mobilize workers to develop a class consciousness.” With the advent of the Second World War, the appetite for folk music’s politicized messages abated, yet, as early as 1947, seeds of a revival started to blossom, taking root in and around Washington Square Park. Sunday-afternoon folk singalongs attracted a cross-section of amateurs and pros armed with guitars, banjos and bongos. By the mid-’50s, the Square had become the epicentre of folk’s renaissance, with more than 20 clubs and coffee houses, including the Gaslight Café, the Village Gate and the Bitter End within a five-block radius.

Musicians blended with Beat poets, abstract expressionists, off-Broadway actors and experimental filmmakers to forge a heady countercultural melting pot. A new breed of stars emerged: the Seeger-helmed Weavers (until Seeger fell afoul of the House Un-American Activities Committee), Harry Belafonte, Peter, Paul and Mary, Judy Collins, Baez and Dylan. Their songs carried antiwar, pro-civil-rights messages across the land, achieving mainstream popularity. Hard-core folkies—Phil Ochs, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott—decried the music’s steady commercialization, as the Village devolved from cultural hub to overrun tourist attraction. By 1965, folk had made way for folk-rock and, led by the Lovin’ Spoonful and the Mamas & the Papas, decamped for California. Musically, New York moved on, though it never entirely abandoned the idiom-cum-social-phenomenon that only its perfect storm of liberalism, intellectualism and artistic freedom could have facilitated. To this day, each fall, there’s a Washington Square Park Folk Festival.