A few years before his death last fall, Steve Jobs gave a commencement address in which he placed surprising emphasis on, of all things, a calligraphy course he took just after dropping out of college. The upshot, the Apple co-founder said, was his insistence on beautiful typefaces in his computers.

A few years before his death last fall, Steve Jobs gave a commencement address in which he placed surprising emphasis on, of all things, a calligraphy course he took just after dropping out of college. The upshot, the Apple co-founder said, was his insistence on beautiful typefaces in his computers.

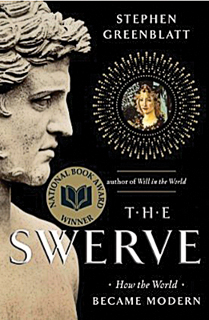

There’s something about the shapes of letters. The central figure in The Swerve, Italian Renaissance book hunter Poggio Bracciolini, was famous in his time for helping invent a more elegant handwriting style. This innovation partly propelled Poggio’s rise from scribe to senior official in the papal court. His fine hand more than hinted at the sophistication of his interest in the books he copied.

Greenblatt, the Harvard professor who made Shakespeare’s London swarm with life in 2004’s Will in the World, is just as compelling conjuring up 15th-century Italy. Greenblatt places Poggio in a circle of brilliant, squabbling humanists who loved pre-Christian books, often all-but-forgotten classics they dug out of monastic libraries. Poggio’s greatest rescue mission was an expedition in 1417, likely to the German abbey of Fulda, where he found On the Nature of Things, by the Roman poet-philosopher Lucretius.

In a sense, the mysterious Lucretius, who died around 55 BCE, is the real hero of The Swerve. Next to nothing is known about his life. But his book, after Poggio put it back in circulation, lived large. In gorgeous Latin verse, it conveys the even more ancient thinking of the Greek philosopher Epicurus. His ideas were potently radical in Poggio’s era and long after: everything is made of atoms that “swerve” around randomly; gods, if they exist, have nothing to do with the material world; and that leaves humans only to pursue pleasure and avoid pain.

Whether this tale of an intellectual watershed fulfills the subtitle’s promise to explain “how the world became modern” is debatable. But by making the life of a 15th-century book lover feel as relevant today as, say, that of a 20th-century computer mogul, Greenblatt accomplishes his own improbable feat of rediscovery.